Participants WW2 - Colin Francis

The following article summarises the life of Pilot Officer Colin Francis until his untimely death in 1940, when his Hurricane aircraft crashed in Stansted, Kent. There are links to three additional event-based articles available at the bottom of this page covering the aircraft and pilot’s excavation and subsequent military funeral, the crash-site memorial, and a commemorative memorial stone, placed near the Stansted War Memorial by the Shoreham Aircraft Museum in March 2024.

Pilot Officer Colin D Francis

Born: 24 May 1921 Died: 30 Aug 1940

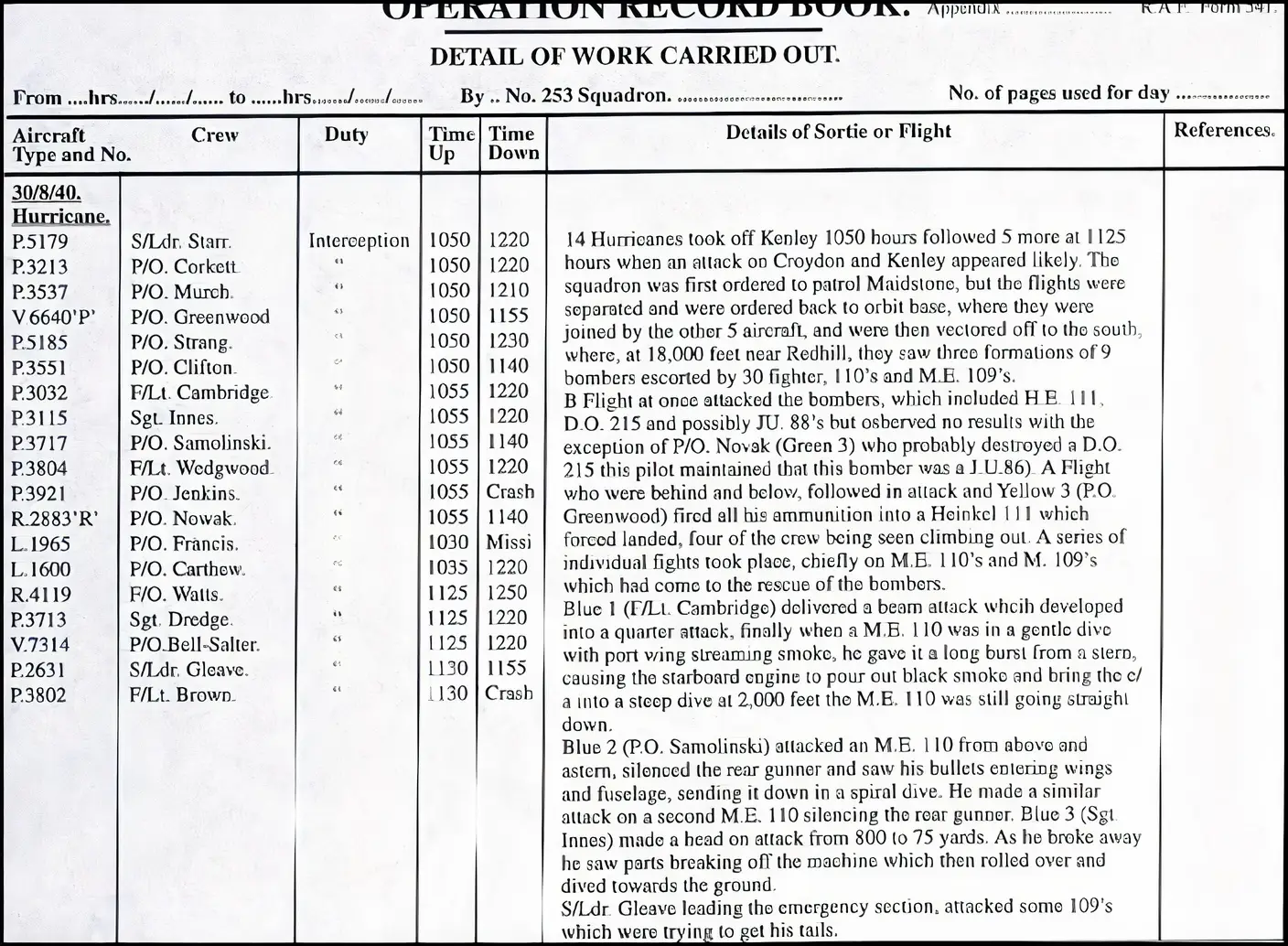

253 Squadron RAF, Killed in Action in Hurricane 1 L1965, which crashed on 30 August 1940, 11:15, near Coldharbour, in Stansted, Kent.

Colin Dunstone Francis, of Stoke d’Abernon, Surrey, was educated at Emanuel School, Battersea, from 1932 to 1939 and joined the RAF on a short service commission in April 1939. He arrived at 6 OTU, Sutton Bridge, on June 2, 1940, and, after converting to Hurricanes, he was posted to 253 Squadron at Kirton-in-Lindsey on June 17, 1940.

After a spell in Scotland, the squadron moved to Kenley on 29 August 1940. On the morning of the 30th, Francis took off in a section of three aircraft to join the rest of the squadron in attacking a force of bombers, which was escorted by some thirty fighters. It was his first encounter with the Luftwaffe, and he was shot down and reported ‘Missing’. His name appears on the Runnymede Memorial, Panel 8.

In August 1981, an aircraft was excavated at Stansted, Kent, on land that had been Percival’s Farm in 1940. It proved to be Hurricane L1965, and Francis’s remains were still in the cockpit. They were buried with full military honours at Brookwood Military Cemetery. Francis was 19 years old when he was killed.

The story of the crashed Hurricane at Coldharbour on Friday, 30th August 1940, is a poignant one if, for no other reason, it underlines the harsh reality of those times, and how the events of that day continued to impact the survivors and relatives for many years thereafter. Several of Colin Francis’s cousins were in attendance at his final internment in 1981, including one who spoke movingly about how it was a great comfort to know that he had finally been found.

When considered in the context of the crashed Me110 behind Stansted Church on the following day, and the recovery of the dead Luftwaffe airman at Rumney Farm two weeks later on 15th September, the crash also highlights how the sky above Stansted featured in some of the fiercest days’ air fighting of the Battle of Britain, and the participants included men who went on to achieve acclaim and fame.

The cold facts are that Colin Francis was just one of 20,287 airmen posted missing, believed killed, with no known grave in WW2. (Source: CGWC Runnymede). The truth was that he lay buried with his aircraft within the parish boundary for over 40 years, out of sight, but doubtless never out of mind to those who remembered him. It was only when the burgeoning interest in aviation archaeology gained traction in the 1970s/1980s that his aircraft was excavated in 1981, with his body still strapped into the cockpit.

Geoff Allgood moved to Windy Ridge in Wrotham Hill Road just before the recovery and was present during the dig. At that time, there were few regulations on the recovery of military aircraft beyond securing the landowners’ permission. However, following many similar digs in which human remains were found, the government introduced the 1986 Protection of Military Remains Act, requiring a licence to be granted.

Although there is now a presumption against granting a licence where there is an expectation of finding human remains and/or ordnance, aircraft continue to be recovered, often at the insistence of relatives, with one such example being the 1996 recovery of Sgt Dennis Noble, whose 43 Sqn Hurricane crashed in a Hove street just 40 minutes after Francis crashed at Coldharbour. Whilst the remains of Noble’s aircraft are on public display at the Tangmere Aviation Museum, likely, various pieces of Colin Francis’s wrecked aircraft are probably now in private collections. (N.B. The Stansted and Fairseat History Society archive has various pieces donated by Geoff Allgood, and the Kent Battle of Britain Museum at the former RAF Hawkinge near Folkestone has a display featuring Colin, including fragments from his aircraft, such as his parachute harness. It also has a display on S/Ldr Starr, Colin’s C.O., also shot down and killed that day, together with the engine recovered from S/Ldr Starr’s aircraft.

There is an added poignancy if one reads the late John Greenwood’s account of the events leading up to Francis’s crash. Greenwood was a fellow 253 Sqn pilot who flew on the same sortie that day and shot down a He111, forcing it to land at Lingfield. (http://www.battleofbritain1940.net/greenwood/253squadron.html)

Unlike Colin Francis, for whom this was his first operational flight, P/O Greenwood was a veteran, having previously shot down three enemy aircraft whilst the Squadron was based in France. During that period, they lost 50% of their pilots in just four days and were reduced to just three serviceable aircraft. According to Greenwood, their three-month rest upon returning to the UK had done nothing to ameliorate the burning resentment felt by some of the pilots at having been forced to fly other squadrons’ cast-off aircraft and having to endure an ongoing leadership crisis as a result of the appointment of a succession of Flight Commanders and Commanding Officers.

It was in this tense atmosphere that Colin Francis was posted in the eleven weeks leading up to his death. This would have been a period of operational training in which he would have had the rough edges knocked off and been brought up to speed with the Squadron’s way of doing things. Given the foregoing, it may not have been an easy time for him, as he would have been very reliant on the willingness of others to impart the necessary information. He was in effect one of the new boys, and whether he encountered any closing of the ranks is a matter for conjecture, but it is telling that Greenwood recalls Francis becoming close friends with another newcomer, Canadian P/O Carthew. Such was their mutual interdependence, the Squadron referred to them as Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

On the day before Colin’s death, the Squadron had flown down from Prestwick in Scotland to Kenley, near Caterham, the epicentre of the daily air combat between hundreds of aircraft that were taking place over the southeast of England. It should be noted that this was at the height of the Battle of Britain, which started in July.

The previous weeks had seen an escalating number of German aircraft attacking RAF airfields, radar stations, docks, ports and coastal shipping. Stansted was on the flightpath to and from the London docks, and its proximity to the airfields at Gravesend, Detling, West Malling and Biggin Hill, all of which had been heavily bombed, meant that the sight of vapour trails overhead, and the sound of machine gun fire would have been commonplace.

Situated just to the west of Biggin Hill, with almost overlapping circuit patterns, Kenley had also been hit hard over the previous two weeks, suffering many casualties. Keeping the runways operational and communications open was an increasing challenge. 253 Squadron had been previously based at Kenley for a brief period before they went to France, so the surrounding area would have been familiar with what remained of the “Old Lags”. But for new boys like Francis, who had hitherto done all their flying in the relatively peaceful and rural skies over Lincolnshire and Scotland, the more densely populated urban outskirts of London may have presented challenges in orientation and navigation.

At dawn on their first day, the Squadron was put on readiness to intercept the inevitable raids. The first was a feint, with aircraft attacking shipping in the Thames Estuary, but at 1030 a much larger raid was picked up on radar assembling over Cap Gris Nez. Sixteen squadrons were scrambled to intercept, with two, including 253 Sqn, tasked to protect Kenley and Biggin Hill (The Narrow Margin: Wood & Dempster 1961). Colin Francis, followed by his friend Carthew, were the first two of fourteen 253 Sqn Hurricanes scrambled to patrol Maidstone in two flights. However, for some reason, the flights lost contact with each other, so all aircraft were ordered to return to orbit Kenley and then join up with the remaining five Squadron aircraft, which were scrambled at 11:25.

The Squadron Operational Record Book times Francis’s crash at 1115, so it seems likely that he was shot down whilst returning to Kenley. The leader of his “Vic” of three aircraft was the co-commanding officer, S/Ldr Tom Gleave. At 32 years of age, and a pre-war flyer, Gleave wanted to command the squadron but was told politely that RAF regulations did not permit Commanding Officers above the age of 26. Somehow, Gleave managed to get part of his way by sharing the command with the newly appointed Commanding Officer, S/Ldr Starr. (Fighter: Len Deighton 1979)

Although an experienced pilot, Gleave had thus far not seen combat, unlike his number two, F/Lt Georgie Brown, who, like P/O Greenwood, was also a veteran of the Battle of France, Gleave recalls being detached from the rest of the Squadron and seeing a formation of Me109’s in the haze about 500 feet above them, stretching as far as the eye could see. Unhesitatingly, he led the formation right through the enemy fighters, firing as he went.

He remembered the scene clearly and described the smell of the cordite, the hiss of the pneumatics, and the way the Hurricane’s nose dipped as the guns recoiled. He gave the first ME109 a four-second burst and saw his bullets hitting the engine. He saw the Perspex of the hood shatter into fragments that sparkled in the sunlight. The 109 rolled onto its back, slewed, and then dropped, nose down, to the earth. Brown’s aircraft received hits and disappeared. Gleave and Francis then turned to engage the aircraft, attempting to regain formation. Another enemy aircraft came into his sights. Gleave turned with him, firing bullets that brought black smoke from the wings before the Me109 dropped vertically, still smoking.

Gleave narrowly missed colliding with his third victim, and then gave him a three-second burst as the Messerschmitt pulled ahead and turned into gunfire. The cockpit seemed empty; the pilot slumped forward out of sight. The Messerschmitt fell. The German pilots were trying to maintain formation, and by now there was so much gunfire curving through the air that Gleave had the impression of flying through a gigantic golden bird-cage. A fourth Messerschmitt passed slightly above Gleave, and he turned and climbed to fire into the underside of its fuselage. But after two or three seconds’ firing, Gleave heard the ominous clicking that told him he had used up all his bullets. But already the fourth victim was mortally hit and rolled on its back before falling away. (Ref: Fighter: Len Deighton 1979)

Of Colin Francis, there was no sign. Gleave recalled “After Brown was shot down, Colin and I went in by ourselves. We went right into the middle of them, and I never saw him again. He was a damned fine kid and full of guts.” (Ref: I had a row with a German: Tom Gleave 1941). F/Lt Brown was badly wounded in the shoulder and leg and force-landed near Mereworth at 11:15, around the same time as Francis’s crash, later admitted to Preston Hall Hospital, Aylesford, Kent.

Whilst Gleave, Brown and Francis were dogfighting over Stansted, the remainder of the Squadron had been vectored to Redhill, where they proceeded to attack a formation of nine bombers escorted by a mixture of thirty Me109s and 110s intent on attacking Farnborough Airfield. During this combat, P/O Jenkins was believed to have been killed by a Me110 after bailing out over Woldingham at 11:20. In addition to the He111 claimed by P/O Greenwood, P/O Novak claimed a Do 215, F/Lt Cambridge a Me110, P/O Samolinski a Me110, and he also damaged another, which was ultimately shot down by Sgt Innes. Although Gleave claimed four aircraft were shot down, shooting down four aircraft in as many minutes was regarded as unlikely by the subsequently convened Air Assessment Board, and his claim was reduced to a probable four.

All of the surviving aircraft had landed back at Kenley by 1220, albeit those flown by S/Ldr Starr and P/O Samolinski were badly damaged. But the fighting was not yet over, as the undamaged aircraft scrambled again during the afternoon and were involved in combat with Me109s over Dungeness. In this combat, Sgt Dickinson bailed out but was found dead on landing near Woodchurch, and F/O Wedgewood brought back a severely damaged aircraft. (Ref: Battle of Britain Then & Now: Winston G Ramsey 1980)

Thus, the squadron accounted for five enemy aircraft shot down, and three probably shot down, for the loss of four of their own aircraft and three pilots. Whilst they had succeeded in preventing an attack on their own airfield, the Squadron tasked with defending Biggin Hill arrived too late to prevent a devastating attack by Ju88s that was the worst of the war, smashing the workshops, barrack blocks, MT Section, WAAF quarters, the transport yard, storerooms, the armoury, both officers and sergeants messes three hangars and on top of all that telephone and communication lines were severed, gas and water mains were ruptured.

Thirty-nine people were killed, and twenty-six were injured. Elspeth Henderson was one of only six WAAFs throughout the war to be awarded the Military Medal for her bravery that day. Detling was also hit. Oil tanks were set ablaze, the main electricity cable was severed, cutting the power to all buildings and hangars and roadways were cratered. (Ref: Eagle Day: Richard Collier 1966)

Overall, that day, the RAF shot down forty enemy aircraft for the loss of twenty-four of their own, with nine pilots killed, three of whom were from 253 Sqn. The Sqn, therefore, accounted for 12.5% of the days ‘kills’, suffered 16.7% of the aircraft losses and 33% of pilot losses, one of whom was Colin Francis, who died in Stansted. The next day, Stansted was again in the thick of it when a ME110 belly-landed at the Court Lodge with its gunner mortally wounded and two Me109s crashed nearby, one in West Kingsdown and one in Knatts Valley.

253 Sqn also lost their CO, S/Ldr Starr, at 08:25, who fell dead at Eastry, apparently machine-gunned by a German fighter as he dangled helplessly beneath his parachute. S/Ldr Gleave assumed command for no more than a few hours before he too had to bail out of his blazing Hurricane over Cudham, from where he was admitted to Orpington Hospital with grievous burns. He was later treated by Sir Archibald McIndoe at Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, where he became one of the first “Guinea Pigs” for plastic surgery. Of the 17 pilots that survived the fighting on 30th August, only 10 survived the war, with 4 killed in September, and another 3 over the ensuing two years. P/O Carthew was so devastated by his experiences that day, and by the loss of his friend Francis, that he never flew again.

Although Colin Francis is not recorded on Stansted War Memorial, Geoff Allgood felt his sacrifice should not be forgotten by the Parish, and in 1987, erected a plaque in his memory close to the crash site on the footpath that leads from Wrotham Hill Road to Coldharbour and each year he places a poppy cross in his memory.

Pilot Officer Colin D Francis was finally laid to rest at the War Graves Cemetery in Brookwood near Woking in September 1981. The RAF provided a full military ceremony in honour of Colin Francis. His coffin was attended by members of the Queen’s Colour Squadron from RAF Uxbridge, and the ceremony was conducted by an RAF chaplain. Three volleys were fired over the grave, which is in a plot reserved for RAF officers.

The following additional articles relating to memorials and commemorations for Pilot Officer Colin Francis are available in the ‘Events’ section of the website and can be viewed by selecting the links below: