WW2 Participants: Peter Nash

Pilot Officer Peter Albert Nash, Service Number 172182. Peter was a Lancaster pilot serving with 630 Squadron at RAF East Kirkby, Lincolnshire. The following narrative details the traumatic events leading up to his death aged 22 on 15 May 1944. He is commemorated on the War Memorial in Stansted, Kent, and is buried in Cambridge City Cemetery, Grave 14308.

Sheila Parker grew up in Stansted and remembers Peter Nash as a tall young man who moved to Parsonage Farm in Hatham Green Lane with his parents in the early part of the war, a memory corroborated by the 1939 Parish Register. He was born in 1922 in Lewisham, and his parents were Alfred and Muriel Nash.

However, his time in Stansted was brief, as he would have been eligible for call-up in 1940/41, and following basic training in the UK, would in all probability have undertaken his pilot training overseas. However, he indeed returned to the village, as he married Winifred Wesson at St Mary’s Church, Stansted, in August 1943. He then embarked on a hazardous career as a bomber pilot, which was cut short by a tragic accident in May 1944.

East Kirkby is a small agricultural village lying at the foot of the Lincolnshire Wolds just off the Sleaford to Horncastle road. With just one pub and a church, it is of similar size to Stansted, and if you ignore the infilling of more recent housing, it looks much as it did during the 1940s, which makes it difficult to believe that between 1943 and 1945 it backed on to an airfield housing around 2,000 RAF personnel. Instead of cattle grazing in the fields, the view from many a bedroom window was obscured by the brooding silhouette of a 20-foot-tall Avro Lancaster bomber parked on a concrete hardstand, its 102-foot wingspan overshadowing the garden. Most days, the silence of the countryside would be rent asunder by the sound of up to 112 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Merlin engines being run up preparatory to around forty of these aircraft being air tested. This would be repeated at dusk as they took off to bomb Germany and occupied Europe, and again in the early hours before dawn when they returned. However, on so many occasions, upon opening the curtains the next morning, sadly, the view would be of a desolate, empty dispersal pan, such was the rate of attrition.

Today, there is little to remind one of this hive of activity. Few buildings remain, and most of the mile-long main runway, dispersals and perimeter track have long since been removed for hardcore. Look closer, however, and the four potato cold storage units are recognisable as the aircraft hangars they once were. And if your visit happens to be on a Saturday or Bank Holiday, you may be forgiven for thinking you have entered a time warp, as the unmistakable crackling and popping of four Rolls Royce Merlin engines being started is a reminder that this is where the Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre is in the process of restoring to flying condition one of only three Avro Lancasters left in the UK. It was from here that in 1944 Peter Nash flew thirteen operations as a Lancaster pilot with 630 Squadron, 5 Group, RAF Bomber Command.

One man serving on the squadron at the same time as Peter was wireless operator Walt Scott. His time at East Kirkby left such an indelible impression, he penned a series of poems, one of which is narrated by fellow squadron navigator Michael Howley and played at the Service of Remembrance held in the hangar at East Kirkby during the annual reunion of the 57 & 630 Squadron Associations and the text is mounted on a memorial plaque near the entrance to the old guardroom.

Note: An audio recording is available in the ‘Poem’ section below this article.

Without Peter’s service record, we do not know where he trained. Still, quite probably, he would have undergone basic assessment at the Aircrew Reception Centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground, where he and his fellows would have been accommodated in the requisitioned luxury apartments surrounding Regent’s Park. There, he would have been graded as “PNB” – suitable for training as a pilot, navigator or bomb aimer. By 1941, the sheer numbers of aircrew trainees meant that all flying training was done overseas, where there was more airspace, better weather and no risk of enemy action. Almost inevitably, he would have been shipped to Canada, the USA, South Africa or Rhodesia before returning to the UK for advanced flying training. This would have been followed by a period of transitional training at an Operational Training Unit (OTU) and finally a posting to a Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU), and possibly a Finishing School (LFS) where he would learn to fly the Lancaster before joining an operational squadron. The whole process took over two years. At some stage, either during his initial training or on his return to the UK, it seems likely that Peter met his future wife, Winifred, as she was serving as a WAAF when they married at St Mary’s Stansted on 14th August 1943.

At his OTU, Peter would have formed the nucleus of the crew he would subsequently fly with on operations. Crewing up was a process unique to Bomber Command. Aircrew of all trades were left in a hangar and told to sort themselves out. Bomb aimer Miles Tripp described it as “being like girls at their first dance, with no one wishing to be left as a wallflower!” (Tripp, 1985)

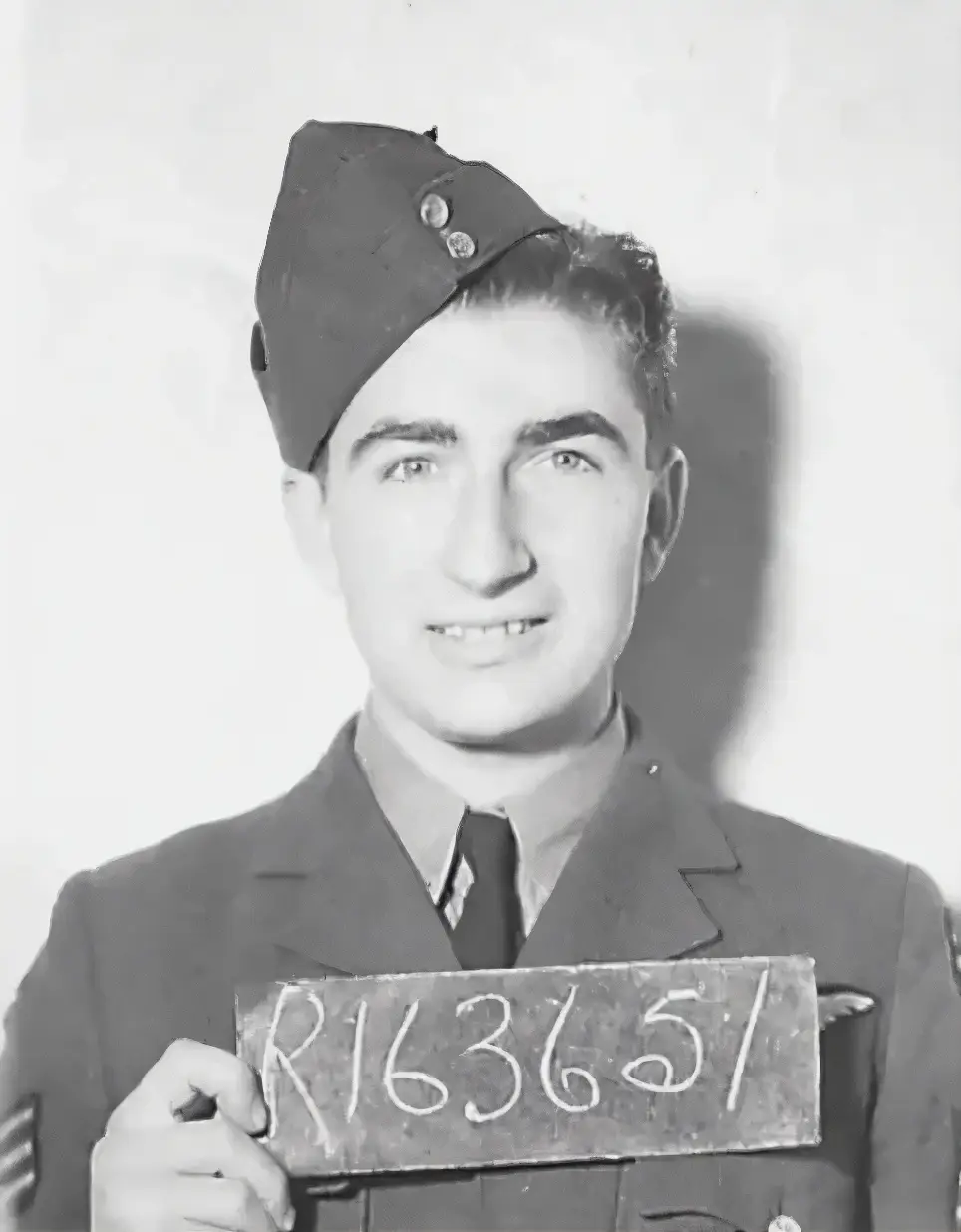

Upon being awarded his RAF Wings, Peter would have automatically been promoted to the rank of Sergeant. By 1944, he had attained the rank of Flight Sergeant, and in February, he was commissioned as a Pilot Officer. (The London Gazette, 10th February 1944). Although sometimes offered commissions during their tour, or upon its completion, most aircrew joining an operational squadron were NCOs, particularly those in the non-PNB category, i.e. the wireless operators, gunners and flight engineers. That said, informality was the norm, and although officers were separately accommodated, the inter-reliance required to make an effective team meant that crews were invariably on first-name terms both in the air and in the pub. One unusual feature of the RAF/RCAF/RAAF/RNZAF command structure compared to that of the Army and Navy was that, even if the pilot was an NCO, he remained the captain regardless of his relative rank to any of his crew, including any officers.

Zena Bamping’s biographies of the names on Stansted War Memorial cite Peter’s first operational posting as 57 Squadron at East Kirkby, following which he was transferred across the airfield on 15th November 1943, to become part of the newly formed 630 Squadron. Their motto was ‘Death by Night’. She then claims he flew with 630 Sqn on their first operation, to Berlin on 18th November. However, the 57 Sqn Operational Record Book (ORB) for Oct/Nov 1943 makes no reference to Peter in the six weeks before the creation of the new squadron. Neither does the 630 Sqn ORB for November list him as flying the Berlin trip, or on any of their subsequent four operations that month. In fact, Peter Sharpe’s comprehensive history of the squadron “Death by Night” confirms that Peter’s crew were one of three that joined the squadron on 28th February 1944.

Note: 22-year-olds also captained the other two crews: P/O Ron Bailey from Northampton and P/O Alan “Happy Jack” Wilson from Australia. One week later, they were joined by the crews of fellow Australian, 21-year-old F/Sgt Lionel “Blue” Rackley and former Edinburgh policeman, 30-year-old P/O John Langlands.

Peter Sharpe’s book, and the squadron ORB and related records, form the basis of the narrative that follows.

The casualty rate at this time of the War was so high that there was little opportunity for new crews to familiarise themselves with their new environment before being sent on operations. However, some pilots were allowed to fly one mission as a supernumerary “second dickey” with an experienced pilot before taking their own crew on operations. Peter’s two contemporaries, P/O Alan Wilson and P/O Ron Bailey, were immediately thrown into the fray on 1st/2nd March as second dickies to ‘B’ flight commander S/Ldr Roy Calvert and F/O David “Robbie” Roberts respectively. One aircraft failed to return.

Note: Founder 630 Sqn member Tanganyikan P/O Peter Piggin’s crew were all killed.

On 10th/11th March, the squadron dispatched eleven aircraft on a raid to Clermont Ferrand from which all returned safely. However, on the 15th/16th, two aircraft failed to return from an attack on Stuttgart.

Note: Of P/O Len Barnes’ crew, he and his flight engineer evaded capture, three were taken POW and two were KIA. Unusually, Len Barnes made it back to the UK to complete his tour with 630 Sqn. P/O Kenneth Rodbourne’s crew were all killed.

Interestingly, although Peter had yet to fly an operation, F/O Johhny Nall’s regular mid upper gunner, Sgt Dixon Burt, was unable to fly, and so Peter’s mid upper, (name redacted), flew as his replacement. Peter’s turn didn’t come until 18th/19th March when he flew as second dickey with Flight Lieutenant “Sam” Weller’s crew to Frankfurt.

Having a second dickey aboard was not popular with experienced crews, as Lancasters were only configured for single-pilot operation. Changing seats with the Captain was a convoluted two-stage process; hence, the second dickey would probably only be given the controls on part of the outbound leg, and similarly on the homeward leg, with the Captain doing the take-off and landing and flying the plane over the target. The second dickey, therefore, spent most of the flight perched on the flight engineer’s drop-down seat, necessitating the engineer to stand behind him or sit on the floor. And the odds against successfully abandoning a diving and spinning aircraft at night were already slim enough without an additional body in the cramped cockpit blocking the way to the forward escape hatch. New crews also feared the prospect of losing their skipper before they had even started, as quite probably they would then be broken up and forced to fly with strangers.

Peter’s first operation was not without incident: of the 37 aircraft dispatched from East Kirkby, that of New Zealander P/O Kenneth Orchiston failed to return. It was the crew’s second operation, and all were killed. F/Lt Ken Ames’s rear gunner was awarded an immediate DFM for shooting down a ME109 which attacked his aircraft over the target.

Note: The medal awarded to Sgt (later P/O) Richard “Paddy” Parle is now on display in the Lincolnshire Heritage Aviation Centre at East Kirkby.

In all probability, Peter’s crew would have stayed up to await his return and would doubtless have breathed a collective sigh of relief when B for Baker, christened by Weller’s crew “Britain’s Big Bertha” (after the WW1 German Howitzer), touched down safely in the early hours of 19th March.

The Nash crew’s operational debut together came four days later when Peter piloted F for Fox on a five-hour forty-minute trip to Frankfurt on 22nd/23rd March. Although all aircraft returned safely, the one flown by original squadron member Warrant Officer Jim White was attacked by a Ju88 and returned so severely damaged that the plane was out of commission for a month. Later that day, F/Lt Weller was notified of his award of an immediate DFC for safely bringing back his aircraft from the earlier Stuttgart raid on which “Britain’s Big Bertha’s” instruments and oxygen failed, as did one of the engines.

With just one day to recover, the Squadrons flew again on 24th/25th, this time to bomb Berlin. Recent arrivals, newly promoted F/O John Langlands and F/Sgt Blue Rackley, flew their second dickey operations with OC “B” Flt S/Ldr Calvert and F/Lt Weller, respectively. That night, Peter’s crew had their first taste of what aircrew referred to as a ‘shaky do’. Flying L for Love, they arrived over the target on time despite having received inaccurate wind broadcasts, which threw them off course and exposed them to flak from several well-defended areas. Over the radio, they would have heard the ‘Master of Ceremonies’ (MC) orbiting the target and directing the stream to bomb on the red target indicators (TIs) dropped by the Pathfinders. The MC had a distinctive Canadian accent, and other pilots remembered that night for no other reason than for his forthright language. Amongst other unprintable comments was his exhortation “These bastards wanted a war, now show them what war is like”. (Middlebrook, The Berlin Raids, 1988)

As Peter held the aircraft straight and level, his Canadian bomb aimer, F/Sgt Derek Todd, would have instructed him to open the bomb doors and begin calling out the minor course corrections required to bring the TI’s into the bombsight. Suddenly, the night sky would turn to daylight as searchlights coned them. When a searchlight locked on, terrifying as it was, the most effective evasive action was to dive down the beam. For the operators twenty thousand feet below, it was as if the aircraft simply vanished as they vainly continued to track an aircraft that had formerly been moving forward at over 200mph.

Blinded by the glare and unable to see the instruments, Peter would have been relying on instinct. He could not allow the speed to exceed 300mph, as the load on the controls would have made it impossible to pull out of the dive, even with the flight engineer furiously rewinding the elevator trim wheel. With the combined weight of the bomb load and half-full fuel tanks contributing to the speed build-up, Peter had to jettison the bombs. It must have been a terrifying and helpless experience for the crew as they became weightless when Peter pushed the nose hard down for what must have felt like an eternity. Each must have felt a palpable sense of relief that the wings did not come off when the G-force pinning them back into their seats indicated he had managed to pull out of the dive.

Note: F/Lt Ron Munday was a pilot from 57 Sqn at East Kirkby who was also coned that night but had a more lighthearted recollection. Although Lancasters had an Elsan lavatory, most pilots were reluctant to entrust the rudimentary autopilot for the length of time it took to trek to the rear of the aircraft and back, preferring instead to make use of a “pee bottle”. On this night, upon reaching the North Sea on the homeward leg, Munday’s crew relaxed, and the bomb aimer distributed the thermos flasks of coffee which had become mixed up in the dive. Unfortunately, he unwittingly allocated himself the one his pilot used for urine!] (‘Silksheen’ Copeman, 1989).

Even then, their ordeal was not over, as bad visibility at East Kirkby meant the squadron was diverted to the satellite airfield at Spilsby. After an incredible seven and a half hours airborne, Peter was the last to return, by which stage Spilsby was also socked in. With little fuel remaining, he must have been exhausted when he eventually landed at the unfamiliar airfield of Dunholme Lodge.

Overall, the raid had been the costliest for Bomber Command to date. The unprecedented 100mph jet stream scattered the bombers, making them easy pickings for night fighters. Of the total of 811 aircraft dispatched, 72 were lost, with 392 aircrew killed, 131 taken prisoner and just four who evaded capture. Between them, 630 and 57 Sqns had dispatched 32 aircraft from East Kirkby, with five failing to return. Of the fifteen dispatched from 630 Sqn, one claimed a ME109 probably destroyed and three were missing, including that flown by the veteran W/O Jim White DFM (KIA) and those skippered by F/Sgt Arthur Perry (POW) and P/O Cliff Allen (KIA).

Allen’s navigator was F/Sgt Tony Leyva. Following the briefing for the raid, he looked suspiciously at his parachute pack. The parachute section assistants smiled as he voiced an unfounded but nagging doubt. It was almost due for its regular airing and repacking, so indulgently they let him pull the ripcord. The counter became swathed in billowing silk, and he murmured his embarrassed apologies as they gave him another, complete, as they always said, with the guarantee “Bring it back if it doesn’t work!”. Hours later, as Leyva worked over his charts, the aircraft rocked violently, and cannon shells raked the cabin. The intercom went dead, and as he reached for his chute, he felt a blast of cold air from the front hatch. He thrust the pack up to the hooks on his chest, just as Allen, dead or wounded, slumped forward over the controls and the plane went into a power dive. Leyva was sent into a mad helter-skelter along the polished leather of his bench, down the floor into the nose and found himself falling through space. He pulled the ripcord, but this time nothing happened. Frantically, he tore at the flaps of his pack, and suddenly a white streak flashed past his face, and he was jerked into a lopsided suspension. Looking up he saw that only one of the two hooks was attached, but he landed safely. Quickly captured, he found he was the sole survivor. The bomb aimer or engineer must have opened the hatch. Had they both been thrown into the nose and been trapped? At daybreak, he was taken to where the wreck of the Lancaster lay in a bog. Still numb from shock, he gazed quite dispassionately at the burnt-out centre section and at the gunners who had been his friends, now dead in their turrets, before his captors led him away. (‘Silksheen’ Copeman, 1989).

At the post-operational breakfast that day, there were thirty-six fewer faces, as Jim White’s crew were also carrying a “second dickey”. That night, there was no respite, and the Nash crew were on the battle order again, back in F for Fox, this time undertaking an uneventful trip to Essen from which all aircraft returned safely.

The same could not be said of his next trip, his fourth as skipper, to Nuremberg on 30th March. This surpassed the Berlin trip as Bomber Command’s costliest operation of the entire war.

Note: At the briefing, 630’s South African CO, Wing Commander Bill Deas, named five crews to go on leave the following day. Not having been known to do this before, the superstitious crews considered this a bad move on his part, and there was a distinct hush. Of the five due to leave, two failed to return, two aborted, and only one completed the raid without trouble. (Middlebrook, The Nuremberg Raid, 1980).

The latter was almost certainly Peter’s crew, as by then, they would have been on the squadron for six weeks, the requisite period for a week’s leave.

Allocated Lancaster ND580, G-George, this aircraft had recently been returned to the Squadron following three weeks of factory repairs resulting from damage inflicted by an FW190 night fighter when flown by P/O Freddy Watts’ crew in late February.

Note: The Watts crew eventually transferred to 617 Dambusters Squadron, where they completed two tours of operations, including all three attacks on the battleship Tirpitz. F/Lt Watts was awarded the DFC and, after the war, flew the aircraft that scattered the ashes of the transatlantic pioneer pilot Sir Arthur Whitten Brown.

However, to say that Peter completed the trip “without trouble” might be considered an understatement, as evidenced by his air gunners’ combat report, which stated:

“At 00:47 hours flying at 21,200 feet, bomb aimer F/Sgt Todd RCAF sighted two ME109’s at 900 yards range on the starboard beam, one had its navigation lights on. The fighters instantly swung around onto the Lancaster’s starboard quarter, and the one without lights opened fire just as the “Monica” early warning system began to earn its keep. The tracer passed by above the bomber as it began to corkscrew to starboard, and the rear gunner, F/Sgt Goehring RCAF, opened fire. Sgt (name redacted) in the mid-upper turret found that his turret was out of action, and the electrical solenoids had failed at the critical moment. The fighters broke off the attack and were not seen again. The gunners made no claim.”

Another of those crews named by Deas at the briefing was that of Australian F/Sgt Lionel ‘Blue’ Rackley, whose crew had joined the squadron shortly after Peter’s. That night, they were flying on their second operation together, Rackley having been initiated on the Berlin trip as the second dickey by Peter’s mentor, F/Lt Weller in T-Tare. In Middlebrook’s book, Rackley described how his navigator came on the intercom to report trouble with his oxygen supply.

No one else was affected, so the flight engineer deduced it was either a problem with the navigator’s tube or the valve to which it was connected. A spare tube could have solved the problem, but they had not flown the aircraft before and did not know there was one on board. Having descended to assist the navigator with his breathing, Rackley realised they had lost too much time and height to continue with the operation and turned for home. However, the decision worried him because he reasoned that some would connect his early return with being on the leave roster, and accusations of lacking moral fibre loomed in his mind. His concern was not without foundation, as the next morning he had to confront his CO. Deas “tore him off a hell of a strip” because a length of spare tube had been found in the aircraft, but Rackley’s defence that he had no way of knowing that made little impression. (Middlebrook, The Nuremberg Raid, 1980)

An accusation of lack of moral fibre or “LMF” was the unspoken dread of aircrew in Bomber Command. All were volunteers, and as such, could not be forced to fly on operations. However, the RAF took a dim view of investing in two years of training only for someone to request a transfer on moral, stress or other grounds. To mitigate this, both carrot and stick were employed. The carrot was that aircrew were only required to fly a maximum of thirty operational sorties. After that, they would be posted to training units as instructors for a minimum of six months before returning for a reduced second tour of twenty operations. The stick was blatantly psychological and used at the discretion of squadron commanders. Unless proven medically unfit by the Station Medical Officer (SMO), transgressors would have their records stamped “LMF” and would be posted off the squadron so as not to “contaminate” others. As a further disincentive, they would be assigned menial duties, and NCOs would be reduced to the lowest rank.

In theory, the same rule applied equally to men who may have wobbled after their first operation, and those who had survived horrific crashes, bailed out or cracked under the strain on their penultimate trip. S/Ldr Jack Currie (Currie, Lancaster Target, 1980) remembered his whole squadron being paraded to witness the discomfiting sight of the Station Commander ripping the chevrons and aircrew brevets from the battledress of two Sergeant gunners, and F/Sgt Miles Tripp was told of a Warrant Officer pilot who hanged himself, such was the extent of his shame. (Tripp, 1985) Understandably, the threat of such treatment was enough to dissuade the vast majority from giving up. Still, many undoubtedly “pressed on” long after they had ceased to function rationally, placing an added burden on their crew.

Rackley’s harsh treatment was echoed by another 630 Sqn crewman who flew that night. Flying B Baker, aka ‘Britain’s Big Bertha’, the aircraft in which Peter had first flown as a second dickie, was P/O Freddy Watts, who had also previously flown Peter’s G-George. His wireless operator was Sgt Dennis Cooper.

Following an earlier raid, Cooper had broken out in boils around his crotch and buttocks, but the SMO still passed him fit for flying. Consequently, his parachute harness crushed the boils, and after debriefing, he fainted when the SMO lanced them with a scalpel. However, he was still required to fly the following night. (Middlebrook, The Nuremberg Raid, 1980)

Much has been written about the Nuremberg raid, which many surviving aircrew believed should have been cancelled due to the weather conditions. A full moon with no cloud cover meant that the bombers were clearly visible to both night fighters and ground defences, and the air temperature caused contrails all the way to the target, making the Luftwaffe’s job even easier. The clear visibility meant that crews, who were commonly used to flying in or above clouds, were unnerved at seeing so many aircraft being shot down around them. Peter’s debriefing report attests to that, citing that, in addition to being attacked himself, he saw tracer from many air-to-air combats from the cockpit of G for George.

Although Peter would have been unaware of it, the RAF had a wireless intercept station less than two miles from his home, at Hollywood Manor, School Lane, West Kingsdown.

Note: One of the WAAF officers at West Kingsdown was Assistant Section Officer Jean Conan-Doyle, daughter of Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who rose to Air Commandant and Director of the WRAF and became an Aide de Camp to the Queen. Post-war, Hollywood Manor was the home of criminal Kenneth Noye and was where he fatally stabbed undercover Detective Constable John Fordham, to whom a memorial exists in School Lane.

Its task was to record German night fighter communications for subsequent analysis at Bletchley Park. It also had a high-powered radio transmitter and three 60-foot aerials, enabling German-speaking operators to issue countermands to frustrate the controller and confuse the pilots. That night, the unit heard the night fighter pilots announcing their victories. Upon shooting down a bomber, the German pilot would call “Sieg Heil” followed by his aircraft call sign.

There were many Sieg Heils that night as ninety-six bombers failed to return, including four from East Kirkby. Those from 630 Sqn were skippered by F/Sgt Ronald Clark on his first trip; Peter’s contemporary, F/O John Langlands, on his third and founder squadron member P/O Allan “Johnny” Johnson from Nassau in the Bahamas on his nineteenth. Night fighters downed all.

Langlands was fortunate to survive being taken prisoner and went on to have a successful police career after the war. However, three of his crew were killed (Sgt George “Jeff” Jeffrey, F/Sgt Alan Drake, Sgt Harry “Bud” Coffey in the above photo) together with ten men from the other two crews, including Clark and Johnson.

Note: F/Sgt Clark was posthumously commissioned. F/O Langlands was flying T Tare, the aircraft in which F/Sgt Rackley flew his second dickey trip with F/Lt Weller.

One of those killed in Johnson’s crew was his navigator, F/Sgt Ernest Farnell, who coincidentally came from Ash near Stansted, Kent, and lived at 4 Billet Cottages at the foot of Billet Hill.

It must have been a very shaken Peter Nash who later that day went on leave.

By that stage of the war, for every two new crews joining a squadron, only one could expect to return unharmed from a tour of thirty operations. The ‘chop rate’ was highest among new crews on their first five trips, when some 40% of all losses occurred. After that, it fell as crews became more experienced after seeing what they were up against. It then began to rise gradually after the twenty mark, when crews realised that they might, after all, survive, and a state of anxiety replaced fatalism. (Middlebrook, The Nuremberg Raid, 1980). Another way of looking at it is that from the beginning of February to the end of March, 630 Sqn lost its entire complement of sixteen aircraft. To survive their second month on operations, the Nash crew would require substantial input from Lady Luck.

We can only surmise, but with five “ops” under his belt, including two “shaky do’s”, and another twenty-six to complete, Peter may have spent the next week in Stansted with Winifred pondering his chances of survival.

On his return, his spirits would have surely been lifted by the news that the Squadron had flown two operations in his absence without incident, but also that Bomber Command was now focusing on shorter-range operations to bomb tactical targets in the occupied countries. However, like all aircrew, he would have been dismayed by the news that these short-duration flights to ‘soft’ targets would only count as a third of an operation, potentially further lengthening the odds against survival.

With no time for reflection, Peter was back on the Battle Order on 10th April. However, it may be that his navigator, F/Sgt Raymond Coates, and bomb aimer F/Sgt Derek Todd had an extended leave, as they were temporarily replaced on this trip by the navigation leader, F/Lt Bob Adams DFC, and F/Sgt George Whitby. Whitby had been P/O Allan “Johnny” Johnson’s bomb-aimer for all their previous nineteen operations, but did not fly on the Nuremberg raid, which claimed his crew (see above). Of somewhat greater significance is that Peter’s flight engineer (name redacted) was also absent from the Battle Order, and for whatever reason, was posted from the Squadron. Instead, Peter was tasked with breaking in a new man, Sgt L. Meace. So, with three relative strangers in the crew, Peter took W-William on an uneventful six-hour trip to Tours and back, all aircraft returning safely in the early hours of the 11th.

That night, with Coates and Todd back in the crew, and with Meace again by his side, they were on again in W-William this time to Aachen. All aircraft returned safely, but several reported seeing fighter activity on the homeward route. In the understated manner of all entries in the squadron ORB, that against Peter’s name states simply: “On leaving the target, the aircraft was attacked by an enemy aircraft and badly damaged by cannon fire but successfully returned to base”. However, the actual combat report contains the following detail:

“Flying at 20,000 feet at 23:02 hours soon after bombing Peter Nash’s ND797 “W-William” was shot up and badly damaged by cannon fire incoming from port quarter down from an unseen night fighter, he made a violent corkscrew to port as their rear gunner Flight Sergeant Ed Goehring RCAF returned fire (130 rounds) into the blackness where he suspected the enemy aircraft to be, his night vision momentarily destroyed by the cannon flashes. The mid-upper gunner Sergeant (name redacted) was unsighted and unable to assist. The Lancaster made it home with damage to its elevators, flaps, the port inner engine and port radiator. No claim was made of damage to the enemy aircraft.” Peter was the last to land at 0059hrs.

Whilst the ORB entries record instances of aircrew being killed in flying accidents or enemy action, those wounded or otherwise scarred do not merit inclusion. What we do know is that, like the Nuremberg trip, this operation resulted in more departures from his original crew. Three were never destined to fly with him again. Navigator F/Sgt Raymond Coates and rear gunner, Canadian F/Sgt Ed Goehring, were off operations for over a month. Although both eventually returned to fly with other pilots, his mid-upper gunner, like his original flight engineer, was subsequently posted from the Squadron. It, therefore, seems reasonable to assume that this ‘shaky do’ surpassed their previous coning by searchlights as their Lancaster commenced 17 days of repairs on-site at East Kirkby.

A week elapsed before the squadron operated again, this time to Juvisy on the 18th. Peter was back in G-George, the aircraft he had flown to Nuremberg, but of his original crew, only his bomb aimer, F/Sgt Derek Todd, and Sgt John Pulham, his Wireless Operator, remained. Sgt Meace, well and truly blooded by two operations in 24 hours, was duly returned to his crew, skippered by P/O Hawker. In his place was another new man, Sgt David Haig. Replacing Peter’s mid-upper gunner was Sgt J Dixon-Burt, who had previously flown at least six operations with F/O Nall, and whose place in Nall’s aircraft on 15th March was taken by the man he was now replacing. He had since flown one operation as a stand-in gunner for P/O Hill, and two for Peter’s contemporary P/O Ron Bailey. Occupying the navigator’s seat was Sgt Charles Wright, and manning the rear turret was Sgt Bill “Taffy” Davies. Wright had already flown several trips with the CO, W/Cdr Deas, but Davies was only on his second operation. His first, in February, was traumatic.

Taking off bound for Stuttgart, his aircraft swung on take-off and careered across the Stickney road at 100mph, causing the undercarriage to collapse. The bomb load exploded immediately with a blast that broke windows in Skegness, fifteen miles away. One of the few parts of the plane intact was the rear turret, from which Davies was helped, miraculously unharmed, the only survivor. Davies had spent two months recovering from shock before bravely returning to operations. (Copeman, 1989).

The following morning, all aircraft returned safely and reported a successful attack on the railway marshalling yards, albeit Peter’s was the only one to encounter flak over the target. In fact, one stick of bombs fell wide, demolishing a block of flats. As this happened to be the local HQ of the German Army, the citizens of Juvisy credited the RAF bomb aimers with a little more skill than they may have deserved! (Copeman, 1989).

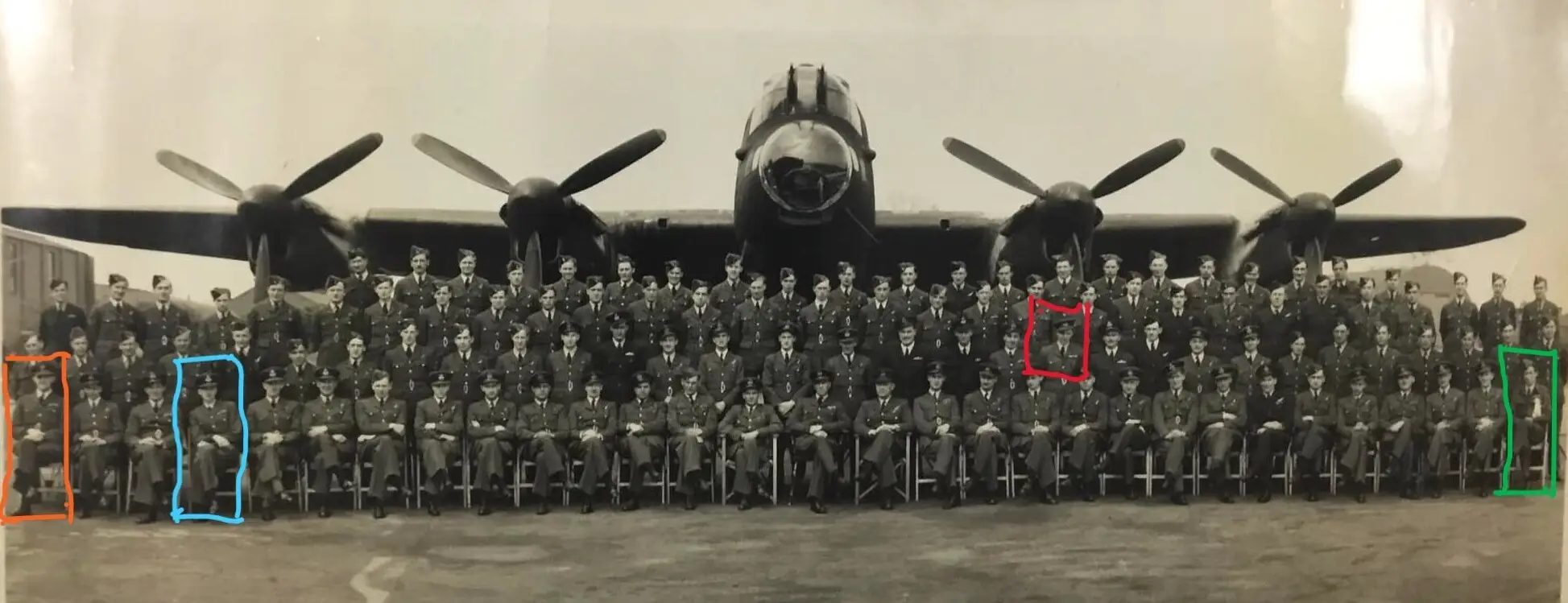

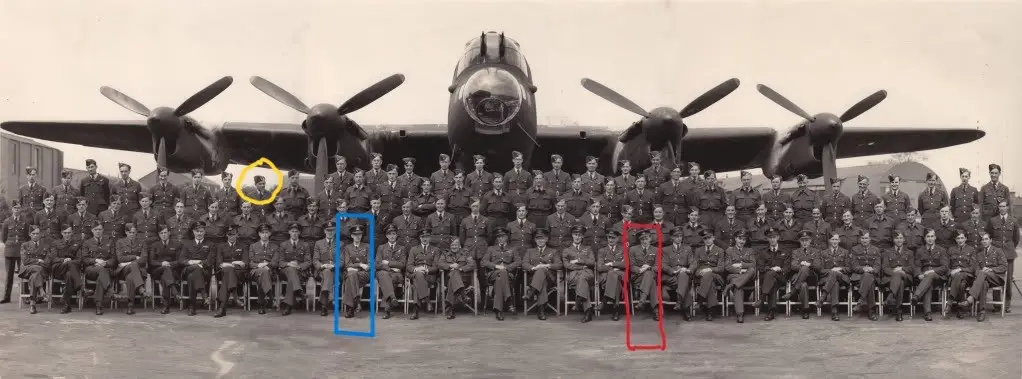

The following 630 Squadron photographs are thought to have been taken on the Squadron’s return from Juvisy on 19th April 1944.

Railway marshalling yards were again the target on the 20th, this time the Gare du Nord at La Chapelle, Paris. Again, all aircraft returned safely, with Peter in G-George reporting one heavy explosion and the target well alight.

On the 22nd, the squadron returned to deep penetration raids into Germany (which counted as a full operation) with a raid on Brunswick. Peter’s crew, along with that of his mentor, the veteran F/Lt Weller, nearing the end of his tour, although listed on the original Battle Order, appear to have been given a short respite, and were sent instead to drop mines in an estuary on the Danish coast on 23rd. Mining sorties were regarded as ‘easy’ trips, as the aircraft did not fly over enemy-held territory and were sometimes allocated to new crews to give them experience, or as a ‘reward’ to crews who had gone through a rough patch.

Alongside Peter for this trip was Sgt Harold Owen, Sgt Haig having rejoined his own new crew under the captaincy of RAAF F/Sgt Vivian “Buster” Brown. Owen had previously flown at least seven ops with P/O Kilgour, but for whatever reason, possibly through sickness, had not flown operationally with him since the trip to Essen on 26th March. Sickness may also have prevented Derek Todd from flying that night, as his place in the nose compartment was again taken temporarily by F/Sgt Whitby, still flying as a “spare bod” after losing his crew over Nuremberg. Aboard Weller’s aircraft as stand-in engineer was Flight Engineer Leader F/Lt Freddie Spencer.

With both aircraft successfully returning the next morning, Peter may well have been grateful that, unlike his contemporaries P/O Ron Bailey and F/Sgt “Blue” Rackley, he was not rostered to fly that night on another deep penetration raid to Munich. As the aircraft took off, Ron Bailey suffered an engine failure and was unable to gain height. He commenced a circuit with the intention of landing, but on the way around, the port outer engine cut out, and he was forced to crash-land on the edge of the airfield. Fortunately, the bombs did not go off, and although the aircraft caught fire, it was quickly put out, and the crew was rescued. Nevertheless, Peter’s new mid-upper Sgt Dixon-Burt must have been thankful he was not in Bailey’s aircraft that night.

There was also fighter opposition over the target that night. F/O Nall’s gunners successfully drove off a Focke-Wulf 190, but “Blue” Rackley was less fortunate, being coned by searchlights, hit by flak and attacked by an enemy aircraft which set the port inner engine on fire, heavily damaged another and cut off the intercom.

With both outer engines shut down, bombs jettisoned, the fire extinguished, and the intercom restored by the Wireless Operator, Rackley decided to head for neutral Switzerland before baling out.

“Unable to gain enough height to clear the Alps, he turned instead towards the Mediterranean, hoping to make southern Italy, which was in Allied hands. In the event, he found an airfield at Borgo, on the east coast of Corsica. As he went into land, he lost one other engine. In the ensuing heavy landing in which the undercarriage collapsed, he swung off the runway, the tail hit another plane, and the rear gunner, F/Sgt Maxwell Dunbar RAAF, was killed when he was thrown out of the open doors of the turret, which was turned to port. The ORB states bluntly that orders had been given for a crash landing and that the gunner should have been at his crash station in the middle of the aircraft, not in his turret.” (Copeman, 1989)

The surviving crew were eventually flown back to the UK via Algiers and Casablanca, mainly by their own initiative, as stranded Bomber Command aircrew were something of a novelty to the authorities in the Mediterranean theatre.

Upon returning to East Kirkby after his enforced three-week sojourn in warmer climes, Rackley was given a hard time by his flight commander, S/Ldr Butler, who, unusually, was a navigator rather than a pilot. According to Rackley, he viewed pilots as a lesser species, and those from the Dominions even more so. Rackley had recommended his wireless operator for a gallantry award for fixing the intercom, but this was not pursued. This was the second time Rackley’s judgment had been questioned. In addition to Rackley’s plane, another did not make it back to East Kirkby, having sustained damage over the target. By contrast, P/O Bob Hooper was awarded an immediate DFC for getting it, and his wounded rear gunner back to Thorney Island in Sussex, something Rackley, in his memoirs, felt to be an example of the prejudice as mentioned above.

On the 26th, the target was Schweinfurt, which was to be the last of the deep-penetration raids, as shorter nights meant aircraft would otherwise be returning in daylight. Flying G-George again, and with Charles Wright continuing as navigator and Harold Owen as flight engineer, the only member of Peter’s original crew was wireless operator John Pulham. With Derek Todd still absent, bombing leader F/O Harker replaced him in the nose, and Peter also had two new gunners. Given that neither Dixon-Burt nor Davies had started their tour with Peter, it may be that they were due for leave and/or were looking to join a crew who had completed the same number of operations as them in order that they could finish their tour with the same pilot.

The new men, Sgts Leonard Page (mid-upper) and Roland Locke (rear), would have been known to Charles Wright, the navigator, as they had previously flown with him as part of the Wing Commander’s crew. Their first trip with Peter, however, was not without incident.

“The raid ran late because of unexpectedly strong winds. All returning pilots reported intense fighter activity from the moment they crossed the French coast on the outward flight. F/O Johnny Nall reported 20 bombers shot down before even reaching the target. In G-George, on track at 0210 hrs, and flying at 15,000 feet, Roly Locke in Peter’s rear turret sighted a twin-engined fighter at 400 yards range below and to starboard. Shouting an instruction for a corkscrew to starboard, he opened fire with a 160-round burst. The fighter broke off its preparation to attack and disappeared as mid-upper Lenny Page turned from his search of the port side. The fighter was not seen again.” (Death by Night, Peter Sharpe 2024).

However, their ordeal was not over, as “George” suffered flak damage once again.

The next morning, three aircraft were missing from East Kirkby. One was skippered by flight engineer Harold Owen’s previous pilot, P/O Joe Kilgour. All on board were killed when the aircraft Peter flew on the mine-laying sortie was shot down – another shaky-do.

A day’s interlude preceded the next operation, to Clermont-Ferrand. With Derek Todd back in the crew and Charles Wright now commissioned as a Pilot Officer, Peter had an uneventful trip in G-George, the aircraft that was now his regular mount. Not so for F/Lt Weller, who was flying his usual “Britains Big Bertha”, the plane in which he took Peter on his second dickie trip. Reacting to a call from one of his gunners, “Sam” Weller threw the aircraft into a corkscrew to port.

“As the FW190 fighter closed for attack, gunnery leader F/Lt Tom Neison in the mid-upper turret fired a three-second burst, with bomb aimer F/O Andy Kuzma contributing a 60-second burst from the front turret and Sgt Howell Jones adding 160 rounds from the rear turret. As the fighter attempted to attack a second time, Neison fired a second three-second burst, which caused it to explode and fall, disintegrating into the Channel, followed by another burst from the nose turret. Witnessed by the entire crew, the claim “Destroyed” was accepted. Neison was awarded an immediate DFC for shooting it down.” (Death by Night, Peter Sharpe 2024).

The raid on Clermont was, in fact, a defining moment for 630 Sqn as it marked the completion of thirty trips for the crew of F/Lt David “Robbie” Roberts, the first crew to have completed a tour having joined the squadron straight from training. On their return, they were interviewed by BBC correspondent Richard North. Roberts was subsequently awarded a DFC, and some members of his crew the DFM.

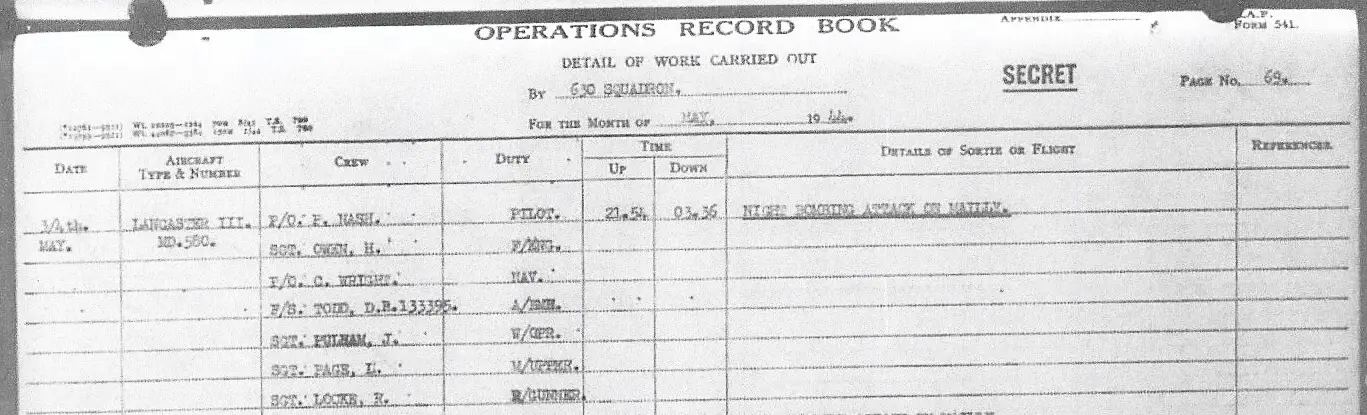

On 1st May, the squadron again bombed the aircraft factory at Tours near Paris, with all aircraft, including Peter, in G-George returning safely.

At 03:36 hrs on 4th May, Peter made a radio call “Silksheen from Gauntley G-George, permission to pancake over” and, upon receiving affirmation, touched down at East Kirkby after a raid on the Panzer Tank training depot at Mailly le Camp. It was his twelfth operation as Captain. It had been the third aircraft to take off from a total of twelve dispatched by the Squadron the previous evening, and the eighth to land. All aircraft returned safely, except for one from 57 Sqn.

The 630 Sqn ORB notes that “the bombing, which took place between 00:07 hrs and 00:30 hrs, was well concentrated, despite smoke obscuring the target; the flak was very accurate, but fighter opposition was intense, with a bright moon working in favour of the defenders on the ground and in the air.” This, frankly, understates what historians now believe to be one of Bomber Command’s biggest blunders of the war, in a raid that was almost as costly, in percentage terms, as Nuremberg.

Both raids had a common factor: clear moonlit skies that gave the night fighters a significant advantage – but the controversy surrounding Mailly was that the planning was overly complex and the crews were inadequately briefed. Unlike previous targets, there were to be two aiming points, each marked by flare-dropping pathfinders. These were to be bombed in quick succession by two different waves of aircraft. As both targets were close together, the second was not to be marked until the first attack was well underway to avoid distraction. Marker aircraft, which flew well below the height of the bombers, would have cleared the first target before the bombs started falling. However, on this occasion, they would need to mark the second target before the bombing on the first had been completed. This required the Master of Ceremonies (MC) to halt the bombing temporarily. However, the MC’s aircraft could only communicate with the Pathfinder leader and the Main Force Master Bomber, whose job it was to relay these instructions to the Main Force. Note: The Pathfinder leader that night was W/Cdr Leonard Cheshire of 617 Sqn, who had succeeded W/Cdr Guy Gibson as CO following the Dambusters’ raid of the previous year. His deputy that night was F/Lt Dave Shannon, and both Shannon and his navigator, F/O Len Sumpter, were survivors of the Dams Raid.

Usually, this would have been by voice command. Still, because it was erroneously believed that some of the Main Force aircraft tasked with the second attack could not receive on the same VHF frequency, these instructions were to be instead transmitted in Morse code by the Master Bomber’s wireless operator. If this long-winded added link in the chain were not enough, few of the Main Force wireless operators recall being briefed to listen out for this, and as it transpired, the instructions were transmitted on the wrong frequency anyway. In a further surreal twist, those second-wave pilots expecting to be called in over the VHF were instead treated to recordings of American dance music, believed to be transmitted for the benefit of the vast numbers of GIs awaiting D-Day in the southern counties of the UK.

Although the initial attack started well, and the first wave obediently obeyed the VHF order to cease bombing, the subsequent commands transmitted in Morse went unheard, resulting in over one hundred Lancasters orbiting the target waiting for instructions. They could see the primary target burning, and they could see flares going down on the second aiming point, but instead of the expected instructions, all they could hear was the strains of ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas’ over the VHF. Meanwhile, the night fighters got stuck in with a vengeance, shooting down bombers left, right and centre. To the circling crews, it was a horrific sight. As Lancasters exploded all around them in giant balls of orange flame and clouds of oily black smoke, some pilots made up their own minds to go in and bomb, and others continued to orbit waiting in vain for commands that did not come. Their frustration and fear manifested themselves when some broke the golden rule of maintaining radio silence.

The following text is taken verbatim from S/Ldr Jack Currie’s book (Currie, Battle under the Moon: The RAF raid on Mailly le Camp May 1944, 1995). Currie had been a Lancaster pilot who had finished his first tour of operations the previous year. “Two of my crew are dead already”, someone shouted, “for Christ’s sake, do something, or we’re all going to die”. Out of the flash-broken darkness came a dusty answer, delivered in a harsh Australian twang: “Die like a man then you yellow bastard. And do it quietly”. That may have raised a sardonic chuckle in some aircraft, but it didn’t stop the protests or the reprimands. “If this is a third of an op”, growled a Canadian voice, “I’m halfway to going LMF” “Shut up”, came a rebuke. “What are the Jerries going to think of the RAF, hearing all this?” “xxxx you, and the RAF. I’m RCAF!” In the POW camps, there was a stock question aircrew asked of each other on arrival. “What was your worst trip?” One man who asked this of his new companion was a navigator who returned from Mailly-le-Camp but was shot down at the end of the month. Expecting a dissertation on the respective claims of Berlin or Nuremberg, his companion, a second tour rear gunner, answered without a moment’s hesitation: “Mailly le Camp”.

Although it would not have been apparent to Bomber Command aircrew for some time, the “chop” rate after Mailly began to fall as the war turned in the Allies’ favour. Some glimmers of hope began to emerge. The recent focus on short-range targets in occupied France and the imminence of D Day gave rise to the possibility that aircrew might now stand a much greater chance of evading capture if shot down. As a result, around this time, sidearms were issued. Whether any training was given is unknown, but in Geoff Copeman’s book (Silksheen: The History of East Kirkby Airfield), he observed:

“….these caught the imagination of most of the younger members, devotees of Wyatt Earp and other Western heroes. It was as well that ammunition was limited to a dozen rounds per man. However, they soon discovered that Sten gun ammo was more readily, though illegally, available and fitted – more or less – the 0.38 Smith & Wesson. However, being rimless, these rounds would slide out of the muzzle unless aimed ‘uphill’. It was rumoured that the local wood-pigeons took to roosting on the ground until the novelty wore off!”

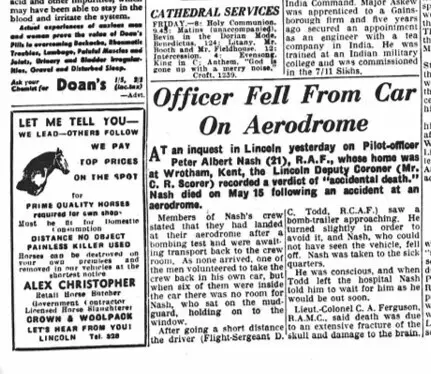

Despite this and given what he had endured in his 13 operational flights, it seems very unlikely that Peter would have felt anything other than the pessimistic fatalism that many Bomber Command aircrew adopted halfway through their tour. So what happened to him between returning from Mailly on 4th May and his death eleven days later on 15th May is a tragedy. The Lincoln Deputy Coroner states the cause of his death as “Head injuries and fractured skull caused by a fall from a motor car. Accidental Death.” The location of his death is given as a military hospital. The 630 squadron research group accessed the adjutant’s report, which baldly stated: “On Saturday, 6th May 1944, he was severely injured when roaring along the perimeter track out to dispersal, he fell from the running board of a small car into which his entire crew was crammed and landed badly. Despite treatment in the Station Sick Quarters and a prompt transfer to Lincoln Military Hospital, sadly, he died as a result of his injuries on 15th May, leaving his crew without a captain. They were split up and became ‘spare bodies’.”

Note: Adjutant F/Lt Charles Martin was a seemingly colourful character. Decorated for bravery as a Lance-Corporal in WW1, he was heavily involved in motor racing at Brooklands between the wars. Commissioned into the RAF at the outbreak of WW2 as an air gunner, he was injured on operations before transferring to admin duties. A General Court-Martial subsequently cashiered him for allowing crew members access to service vehicles and fuel for recreational use.

A coroner’s inquest was held, and the press cutting reveals the whole sad story.

It is almost beyond comprehension to think that Peter brought his aircraft back from the carnage in the skies over Mailly, only to die because of an accident. And a tragic irony that, having returned his crew safely from twelve operations, the purpose of his last flight was to test the proficiency of his bomb aimer, who was driving the car from which he fell. He lies buried alongside many of his contemporaries in Cambridge City Cemetery in the section used by the RAF for casualties from its East Anglian airfields. His inscription reads:

HE PASSED THE WAY OF HEROES. WE MISS HIM EVERY DAY. WE ARE ALWAYS REMEMBERING THE THINGS HE USED TO SAY.

His hospitalisation and subsequent death must have been a great shock to his crew, who now faced the unpopular prospect of flying with other pilots as the need arose, which is precisely what happened.

Just one day after the accident, for the next op to Tours on the 7th, Peter’s navigator, Charles Wright, and gunners Lenny Page and Roly Locke were re-assimilated back into W/Cdr Bill Deas’s crew. Deas apparently invited the Base Commander and former CO of neighbouring 61 Sqn at Coningsby, W/Cdr Stiddolph, to take flight engineer Harold Owen, and bomb aimer Derek Todd as part of his crew.

Note: Squadron COs were only obliged to fly one operation a month, as the risks to the senior command structure were too significant. That night, one of the Flight Commanders, S/Ldr Calvert, was also flying, so Deas must have had a good reason to risk three senior officers flying on the same raid. That said, it was not unheard of for neighbouring squadrons to plug gaps or share expertise, as was the case one month later when W/Cdr Guy Gibson temporarily transferred from Coningsby to East Kirkby to fly two refresher trips with a 630 Sqn Flight Commander following his return from rest after leading the Dambusters raid.

All squadron aircraft returned safely, as they did from the next raid on Annecy, albeit none of Peter’s crew participated.

However, the Bourg Leopold trip on the 11th cost the Squadron two aircraft out of the nineteen dispatched. One was G-George, Peter’s regular aircraft, and the one in which he had brought his crew back safely from Nuremberg and Mailly. Skippered by P/O Alfred “Bob” Jackson, the names of the crew appear on the RAF Memorial to the Missing at Runnymede. Among them is Sgt Harold Owen, aged 25, Peter’s flight engineer. Whether Peter knew, we will never know, as just four days later, he too was dead. Neither will we know if he was aware, but the controversial third of an op rule for French targets was abandoned five days earlier. (Currie, Battle under the Moon: The RAF raid on Mailly le Camp, May 1944, 1995)

Note: Research by the pilot’s nephew, Jack Porter. Capt. RN (Retd) concludes that G-George was shot down by a Heinkel 219, flown by pilot Hauptmann Ernst-Willhelm Modrow and his Wireless/Radar Operator, Feldwebel Peter Erich Schneider. Both men survived the war, and Modrow was highly decorated for his 34 victories. He died in 1990, and Schneider in 2006.

Although their luck held for a little longer, other members of Peter’s crew and some of those he knew well also paid the ultimate price. Two died less than a week later. Having recently returned to operations following the disastrous Nuremberg raid, his first navigator, F/Sgt Raymond Coates, aged 21, was killed on 22nd May, in F-Fox, the aircraft in which he had navigated Peter to Essen. Also shot down and killed that night together with his entire crew was Peter’s contemporary, P/O Ron Bailey.

Note: Ron Bailey’s flight engineer was P/O Max Whiting. (See “B” Flt photo). After the war, Whiting’s widow remarried, becoming the second wife of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding who commanded RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain.

The following night, Peter’s first temporary flight engineer, Sgt David Haig died along with his recently commissioned skipper, P/O “Buster” Brown and the entire crew on a raid to Brunswick. They were shot down over the North Sea and are all commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

On the night of “D” Day, W/Cdr Deas led the Sqn on a low-level mission in support of the Allied bridgehead in Normandy, targeting the Caen bridges just ahead of the advancing forces. P/O “Happy Jack” Wilson, who joined the Sqn at the same time as Peter, was killed, along with three of his crew, victims of a prowling nightfighter.

One of the other pilots saw their demise: “…we watched the flames and saw the parachutes open one by one. Jack stayed at the controls and saw his crew out safely, not being able to get out himself before he ploughed in”. (Source: “Death by Night, Peter Sharpe 2025)

Two weeks later, four more were dead, all killed on the same raid to Wessling. It was East Kirkby’s worst ever raid with eleven aircraft failing to return from the thirty-seven dispatched. Gunnery leader F/Lt Tom Neison DFC died with the entire crew of P/O Bob Hooper DFC. Of those who flew with Peter, F/Lt Bob Adams, the navigation leader, was killed with the whole crew of the new flight commander, S/Ldr Foster DFC. Peter’s original rear gunner, Ed Goehring, now a Warrant Officer, having been transferred to 57 Sqn, also died with his entire crew. And destiny finally caught up with recently commissioned P/O Bill “Taffy” Davies, who briefly replaced Goehring prior to Roland Locke joining the crew. After leaving Peter’s crew, Davies became “Blue” Rackley’s rear gunner, replacing Max Dunbar, who was killed in the crash in Corsica. That night over the Dutch coast, Rackley, now a Pilot Officer, and flying a replacement G George, was attacked by a Ju88.

With very little available directional control, Rackley decided to jettison his bombs and return to base. Over the Channel, it became clear he would not be able to make a safe landing, and it was decided the crew would bale out as soon as they reached England. Unfortunately, Davies’s parachute had been damaged in the fighter attack. Without hesitation, the bomb aimer volunteered to take him on his own chute. A length of rope was found, and the two men tied together, but when the chute opened, the makeshift lashings failed, and Davies fell to his death, the fate he had so narrowly avoided when he was the sole survivor of the crash back in February. (Copeman, 1989).

Bomb aimer F/Sgt Doug Morgan RAAF was awarded the BEM for his bravery. Rackley sustained arm injuries in the bailout over Luton when his parachute got caught in a London-bound express train. His wireless operator (whom he had previously recommended for a medal) was so shaken that he refused to fly again and was accused of LMF.

Note: Rackley’s recommendation was subsequently taken on board as in recognition of this man’s previous trips with P/O Kilgour (KIA), and P/O Ron Bailey (KIA), he was actually commissioned and completed his tour with the crews of Sgt Mallinson, W/O Nunns (from whose aircraft he was forced to bail out a second time) and P/O Clifford. To hear F/O Lionel Rackley DFC’s account of his RAAF career, including this and his subsequent operations with 630 Sqn, the author commends the reader to visit http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/853-lionel-rackley for a compelling illustration of just what it was like to be a Bomber Command Lancaster pilot on the same unit and at the same time as Peter Nash.

Subsequently promoted to F/O, Rackley didn’t return to East Kirkby until November 1944, when he was awarded the DFC, put on light duties, and told he was not required to complete his remaining 15 operations. He was repatriated to Australia in Spring 1945.

On 8th July, W/Cdr Bill Deas, Charles Wright, Roly Locke (by this stage commissioned P/O), Lenny Page, and all but one of their crew were killed. It was Deas’s 69th operation. (Copeman, 1989)

Note: Sole survivor of W/Cdr Deas’s crew, wireless operator and Signals Leader F/O Wally Upton suffered ill-treatment at the hands of the SS and Gestapo, including being threatened with imprisonment in a Concentration Camp.

In less than three months since the camera shutter clicked on 19th April, half of the men pictured had disappeared. The only man who flew every single operation with Peter was his wireless operator, Sgt John Pulham. The Operational Record Book states that following Peter’s death, Pulham flew with P/O Faulkner’s crew. Faulkner was lost on 11th September 1944, but Pulham was posted from the Sqn that August, having completed his tour. After the requisite six months spent instructing, he bravely volunteered for a second tour of operations with the elite 83 Pathfinder Sqn. Tragically, he was admitted to RAF Military Hospital Rauceby dangerously ill on 9th May 1945, just one day after VE Day, where in a bizarre coincidence, he died the next day of a subarachnoid haemorrhage, almost precisely one year after his former skipper died of brain damage in the same hospital.

For anyone with a modicum of imagination, disused RAF Bomber Command airfields are undoubtedly places that evoke the tenuous link between the living and those taken violently before their time. A crumbling concrete dispersal pan still provides a tangible link between the current day and the many men for whom it was their last contact with earth. Little wonder that so many are reputed to be haunted, and none more so than East Kirkby, from where 845 young men failed to return. Anyone with an interest in the paranormal may view the video following this article in which controversial medium Derek Acora apparently makes contact with some spirits who either occupy or return to the place that retains a link to their mortality. Among them is Sgt John Pulham. The dialogue runs as follows:

“My name is John Pulham. Everyone forgets me. Why do you forget me?

Dearing (indistinct) comes here too. My good friend Dearing (indistinct) comes here too.

He had strength. He had bravery. He helped us”

Could “Dearing” be “Goehring”, Peter’s Canadian rear gunner who twice successfully defended them from fighter attack? Who may have held the crew together in difficult times? Who was quite possibly wounded but returned to operations only to die with another pilot?

Note: A film clip is available in the ‘Video’ section below this article.

Of the six aircraft Peter flew operationally, only L-Love, the plane in which he had been coned, survived the war. (Robertson, 1964) Following the loss of Peter’s much-repaired G-George, and then that of Rackley’s, the code was applied to two more aircraft, both of which were also destroyed. In total, the squadron had lost more G-Georges than any other code to the extent that by 1945, crews began to regard it as a jinx, and it was never used again. (Copeman, 1989)

Peter’s name is the last of six inscribed on the Stansted War Memorial, which is logical given the alphabetical order of his surname relative to the others. However, it appears to have been added as an afterthought, as the Stansted War Memorial is unusual in that, except for Peter’s placement, all names are actually listed in descending rank order rather than alphabetical order. Neither was he the last to die, nor was he (in the context of the First World War names) the only person to die in an accident, which in any event occurred whilst on active service. Adherence to the rank protocol should therefore have placed Peter’s name as third, rather than sixth, i.e. after Wing Commander Hohler and before Petty Officer Hooper.

Regardless of his tragic accident, by virtue of his age, Peter Nash had the misfortune to complete his training and join a Bomber Command squadron at the tail end of the worst time in its short history.

Radar-directed defences were at their peak, with night fighters particularly effective, able to approach unseen beneath a bomber and fire obliquely upwards at the fuel tanks, causing a conflagration. Following on from “D” Day, the nightfighter defences gradually weakened due to shortages of aircrew, aircraft and fuel; flak positions retreated, and many Bomber Command air gunners completed their tours without ever firing a shot in anger. The Bomber Command loss rate improved accordingly, and by 1945, crews stood a much better than even chance of completing their tour and/or evading capture.

However, of the four pilots who joined the Sqn at the same time as Peter, two survived, but neither completed a tour. Bailey and Wilson were shot down and killed. Langlands was shot down and became a POW, and Rackley lost two crew members in two different incidents and suffered injuries sustained in bailing out of his doomed aircraft over England. In theory, even with the poor odds of early 1944, of those four pilots, at least two should have completed their tour, but neither did.

Over the years, Bomber Command’s targeting of the civilian population has received significant criticism on both moral grounds and as to whether it was militarily justified. This controversy was doubtless behind the decision not to award the aircrew a campaign medal after the war, an omission only recently rectified, far too late for most of the survivors. What cannot be challenged is the bravery of men who faced impossible odds, and the stress they faced living a surreal double life: able to enjoy the normality of an English pub one night, whilst having to contend with the prospect of violent death, injury and/or captivity the next. Fifty-five thousand of them died. Death is a terrible prospect, but to be trapped in a burning aircraft, or to fall twenty thousand feet without a parachute, must have been their worst nightmare. Many were never able to come to terms with their experiences and suffered in silence for the rest of their lives, refusing to talk. “Awesome” is now a much-devalued adjective, but it seems singularly appropriate to describe the exploits of a twenty-two-year-old man who single-handedly flew a thirty-ton, four-engined unpressurised aircraft with no power-assisted controls, loaded with high explosive, at night on instruments, for six or seven hours, on thirteen occasions, including three of the RAF’s worst raids of the war.

Note: Two Victoria Crosses were awarded to aircrew who flew on two of the raids flown by Peter: One, to flight engineer W/O Norman Jackson for his gallantry on the 26th/27th April raid on Schweinfurt, the other, posthumously, to P/O Cyril Barton for his efforts in getting his battle-damaged Halifax back from Nuremberg on 30th/31st March.

After the war ended, Sheila Parker believes the Nash family moved from Parsonage Farm. However, she thinks that after leaving the WAAF, Winifred went on to live in one of the Horse and Groom Cottages and was an occasional teacher at the School. It would appear she never remarried, as the probate office records Winifred Nash dying in Eastbourne in 1980, aged just 62. According to Aspects of Kentish History, neither did Ernest Farnell’s widow, Alfreda, who moved to Hartley and died in 2007. Although Peter had two younger brothers, Ancestry records the youngest, Norman, dying aged twelve as an evacuee in Wales. Middle brother Derek appears to have followed his older brother Peter into the RAF, as his address in 1955 is given as Station Workshops, RAF Honington, Suffolk. He and his wife both died childless in 1991.

Lionel Rackley died in 2019. Sadly, no one is left who could either produce or corroborate a photo of Peter that would definitively preserve his memory on this website. However, as indicated earlier in this article, 630 Sqn historian Peter Sharpe believes him to be one of the four pilots outlined in orange, green, red and blue in the three squadron photos earlier in this article.

The author believes these four can be narrowed down to just two. We know that “Sam” Weller was definitely in “A” Flight as he is named by several independent sources in both the whole squadron and “A” Flight photos. We also know from his own account that “Blue” Rackley was also in “A” Flight under S/Ldr Butler. As both “Blue” and Peter flew their “second dickey” trips with Weller, it is reasonable to assume that Peter served in “A” Flight, and is therefore either the pilot outlined in red, or the one outlined in blue.

The one on the left has dark rings around his eyes, possibly a result of little sleep after returning from Juvisy; has his top button undone “fighter pilot style”, wears his cap at a jaunty angle and appears to have removed the peak stiffener to give it the coveted “50 mission” look. The other appears older than twenty-two and is more composed, possibly from being in a ground staff role, but the reader must make their own judgement.

Ultimately, in remembering Peter’s accomplishments, it is fitting that the statue under which his name is engraved on Stansted War Memorial was sculpted by Faith Winter, the artist who also created the statue of his Commander in Chief, Sir Arthur Harris, outside the RAF Church of St Clement Danes at the junction of the Strand and Fleet Street. Although Peter’s association with Stansted may have been fleeting, it is sobering to walk the footpaths he may have walked and look at the unchanging landscape and not be moved by his bravery and sacrifice.

Poem - The Old Airfield

‘Old Airfield’ by former 630 Sqn wireless operator Walt Scott, and narrated by fellow squadron navigator Michael Howley. “SILKSHEEN” was East Kirkby’s call sign. It is played at the Service of Remembrance held in the hangar at East Kirkby during the annual reunion of the 57 & 630 Squadron Associations and is mounted on a memorial plaque near the entrance to the old guardroom.

Video - RAF East Kirby

The Angry Ghost of A WW2 Airman Awaits the Crew: RAF East Kirkby, Most Haunted, S2E11, published by the Documentary Vault channel. At 14:25 seconds from the start, Medium Derek Acora apparently makes contact with Peter’s Wireless Operator John Pulham and possibly Peter’s rear gunner, Edward Goehring.

Abbreviations / British Army equivalent

Sgt – Sergeant

F/Sgt – Flight Sergeant / Staff or Colour Sergeant

T/Sgt – Technical Sergeant (USAAF) / Staff or Colour Sergeant

Flt/O – Flight Officer (USAAF) / Warrant Officer or Sergeant Major

W/O – Warrant Officer / Warrant Officer or Sergeant Major

NCO – Non Commissioned Officer

P/O – Pilot Officer / Second Lieutenant

F/O – Flying Officer / First Lieutenant

F/Lt – Flight Lieutenant / Captain

S/Ldr – Squadron Leader / Major

W/Cdr – Wing Commander / Lieutenant Colonel

G/Capt – Group Captain / Colonel

Sqn – Squadron

Flt – Flight

OC – Officer Commanding

CO – Commanding Officer

RAFVR – Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

RCAF – Royal Canadian Air Force

RAAF – Royal Australian Air Force

RNZAF – Royal New Zealand Air Force

USAAF – United States Army Air Force

DFC – Distinguished Flying Cross / Military Cross

DFM – Distinguished Flying Medal / Military Medal

BEM – British Empire Medal

KIA – Killed in action

POW – Prisoner of War

Author: Mike Goddings

Editor: Tony Piper

Acknowledgements:Bennett, T. (1986). 617 Squadron: The Dambusters at War. Patrick Stephens. Copeman, G. D. (1989). Silksheen: The History of East Kirkby Airfield. Midland Counties Publications. Currie, J. (1980). Lancaster Target. Goodall Publications. Currie, J. (1995). Battle under the Moon: The RAF raid on Mailly le Camp May 1944. Air Data Publications. Middlebrook, M. (1980). The Nuremberg Raid. Penguin. Middlebrook, M. (1988). The Berlin Raids. Penguin. Robertson, B. (1964). Lancaster: The Story of a famous Bomber. Harleyford Publications. Sharpe, Peter. (2025). Death by Night. (Aviation Books Ltd.). The London Gazette. (10th February 1944). Supplement. Tripp, M. (1985). The Eighth Passenger. Macmillan.

Last Updated: 11 December 2025