Luminaries: Sybil Thorndike

Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike CH DBE was an English actress who toured internationally in Shakespearean productions, often appearing with her husband Lewis Casson. Bernard Shaw wrote Saint Joan especially for her, and she starred in it with great success. She was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1931 and Companion of Honour in 1970. She and her husband owned and lived at Cedar Cottage, Wrotham Hill Road, Stansted, Kent, from 1950 to 1960.

Sybil Thorndike was on stage for 65 years and played well over 300 roles. She appeared in many theatrical genres: Greek tragedy, drawing-room comedy, revues, poetic drama, farce, and others. Her record indicates her remarkable versatility and her desire to take on every kind of role. John Gielgud described her as “one of the rarest women of our time”. She became a national institution, loved, admired, and respected. Her dedication to her work and her profession was legendary, as was her unstinting support for good causes and her steadfast socialist and pacifist beliefs.

Sybil was born on the 24th October 1882 in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, to Arthur John W. Thorndike and Agnes Macdonald Bowers. Her father was a canon of Rochester Cathedral. She was educated at Rochester Grammar School for Girls and first trained as a classical pianist, making weekly visits to London for music lessons at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

Her childhood home in Rochester has been renamed in her honour. She gave her first public performance as a pianist at the age of 11, but in 1899 was forced to give up playing owing to a wrist injury. At her brother Russell Thorndike’s instigation, she trained as an actress under Elsie Fogerty at the Central School of Speech and Drama, then based at the Royal Albert Hall, London.

At the age of 21, she was offered her first professional contract: a tour of the United States with the actor-manager Ben Greet’s company. She made her first stage appearance in Greet’s 1904 production of Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor and went on to tour the U.S. in Shakespearean repertory for four years, playing some 112 roles.

In 1908, she was spotted by the playwright George Bernard Shaw while understudying the leading role of Candida on a tour directed by Shaw himself. There she also met her future husband, Lewis Casson, and they were married in December 1908, having four children: John (1909–1999), Christopher (1912–1996), Mary (1914–2009), and Ann (1915–1990). Lewis’ brother’s son was Sir Hugh Casson, the architect.

Jonathan Croall, in his detailed book “Sybil Thorndike – A Star of Life”, wrote “Shortly before a trip [to Ireland in 1908] they had spent a day with Barker [Harley Granville Barker] at Court Lodge, his small Elizabethan house in Stansted in Kent. Sybil had played on his pianola, a gift from Shaw [George Bernard Shaw], and then on his piano, Barker telling her, “I don’t want any expression, I only want notes.” This curious request may have caused what Sybil later described as “a tremendous argument about music.” Now in Dublin, they met him once again. Barker had contracted typhoid fever from drinking infected milk, collapsed and nearly died. On recovering, he met Sybil and Lewis, and Sybil played Bach to him. The company then moved on to Cor,k where, because of a tight schedule, they had to speed up the last performance, reducing Candida to an hour so that they could catch their train and boat connections to be home in time for their wedding.”

She joined Annie Horniman’s company in Manchester (1908–1909 and 1911–1913), went to Broadway in 1910, and then joined the Old Vic Company in London, playing leading roles in Shakespeare and in other classic plays. After the First World War, she played Hecuba in Euripides ‘The Trojan Women” (1919–1920), then from 1920 to 1922, Thorndike and her husband starred in a British version of ‘France’s Grand Guignol’ directed by Jose Levy.

Her husband, Lewis, and her brother, Frank, served in WW1. Lewis became a Major in the Royal Engineers and won the Military Cross. Unfortunately, her brother died from wounds sustained during the Passchendaele offensive in 1917, and Sybil’s father never recovered from the news of his son’s death. Two weeks before Christmas, accompanied by his wife and Sybil, he attended evensong at the church. He sang the vestry prayer, and as the choir sang Amen, he suffered a heart attack and sadly died. Arthur Thorndike was buried in Aylesford at the church where he had been the vicar for seven years, and where Sybil and Lewis had been married.

With the death of Canon Thorndike, the vicarage passed to the next incumbent. While they looked for a home they could afford, Sybil and Lewis rented Holly Tree Cottage, one of two seventeenth-century brick and stone cottages in West Kingsdown. In her book ‘West Kingsdown – The Story of Three Villages in Kent’, Zena Bamping says, “One Kingsdown observer of the time was the writer, John Casson, the son of Lewis Casson and Dame Sybil Thorndike. In his book ‘ Lewis and Sybil’, the writer, who was living from 1915 to 1918 at both the Old Cottage and Stacklands Cottage, School Lane, discusses how his father Lewis had joined up in August 1914, was wounded in 1916 at the front, and spent some of his invalid leave in Kingsdown. The whole family found the quiet of Kingsdown a change from the Zeppelin raids on London and the horrors of the Western Front.”

Their options in London were limited, and they had to settle for a tiny house at 35 Wood Street (now demolished) in Westminster behind Millbank Gardens. It was a slum area…the house was a converted shop over an archway…it had been damaged by a bomb, leaving a hole in the roof and through every floor, and the windows were either boarded or bricked up.” Fortunately, some close friends offered them a house in Kensington rent-free. New House was a vast building with forty-two rooms, located on the corner of Airlie Gardens and Campden Hill. The family stayed for nine months and, with the help of Lewis’s wealthy aunt, obtained an eleven-year lease on a Victorian house at 6 Carlyle Square, Chelsea.

In 1919, Sybil experienced “the most thrilling day of my life so far” when, at the Guildhall in Rochester, with her mother, husband, and brother in the audience, she received the freedom of the city of her childhood.

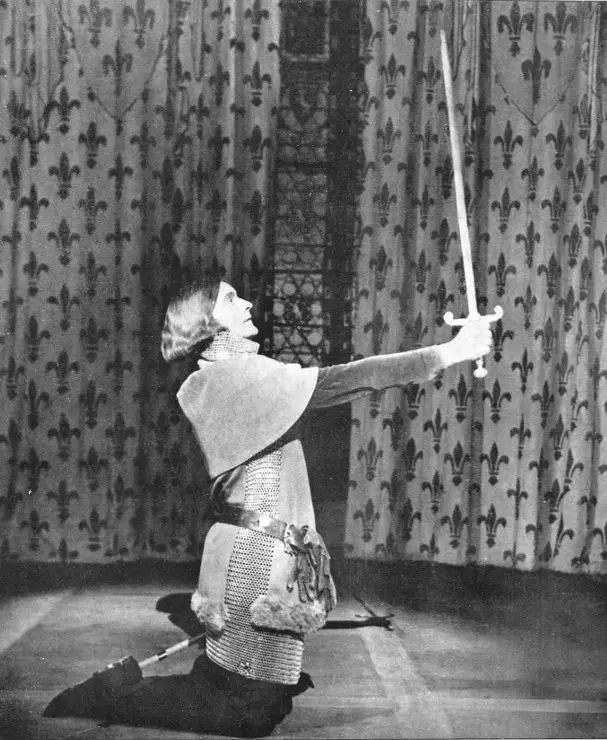

She returned to the stage in the title role of George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Saint Joan’ in 1924, which had been written with her specifically in mind. The production was a huge success and was revived repeatedly.

Both Sybil and her husband, Sir Lewis Casson, took a keen interest in politics and were supporters of the Popular Front government in Spain during the Spanish Civil War, which was fighting against the Nazi-supported forces of Francisco Franco. She joined Emma Goldman, Rebecca West, Fenner Brockway and C.E.M. Joad in establishing the Committee to Aid Homeless Spanish Women and Children. Both she and Lewis held strongly left-wing political beliefs and were active members of the Labour Party, to the extent that, when the 1926 general strike cut short the run of “Saint Joan”, they remained strongly on the side of the strikers. On a trip to South Africa in 1928, she and Lewis aggressively fought segregation so that black theatregoers could attend their performances.

Dame Sybil and Sir Lewis had a loving but sometimes stormy relationship. Once, when asked whether she had ever considered divorcing him, she replied: “Divorce? Never. But murder often!”

She was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1931. During the Second World War, she was a pacifist and raised money for the Peace Pledge Union by giving theatrical readings across the UK.

The photograph is of the Old Vic Travelling Theatre Company, taken in Wales in 1941. Ann Casson (standing left), Dame Sybil Thorndike (seated centre) apply stage makeup as they prepare for a performance of ‘Medea’ at the Settlement Hall in Trealaw.

During the Second World War, Thorndike and her husband toured in Shakespearean productions on behalf of the Council for the Encouragement of the Arts, before joining Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson in the Old Vic season at the New Theatre in 1944. At the end of the Second World War, it was discovered that Thorndike was on “The Black Book” or Sonderfahndungsliste G.B. list of Britons who were to be arrested in the event of a Nazi invasion of Britain.

Following VE Day in 1945, Sybil, together with Olivier, Richardson and 62 other members of the Old Vic company, undertook a post-war tour of Europe. They travelled first to Antwerp, Brussels, Bruges and Ghent, and then on to Germany, where they played at the Belsen concentration camp, before ending in Paris.

Jonathan Croall continues that in 1950, “The time had now come to sell Bron-y-Garth [their home in Wales]. While Sybil loved the place, Lewis found it increasingly depressing; at one point, he considered having the house exorcised. As Diana Devlin put it: ‘It had a powerful and brooding atmosphere, which either enveloped you in a romantic attachment to the place, or drove you to black, despairing moods and melancholy’. Mary and Patricia had left during the war and moved to Surrey, and with the family using it less frequently, they now sold it for £5,000 and instead bought Cedar Cottage, near Wrotham, in Kent.

Croall describes it as “A charming, secluded and somewhat ramshackle early 17th century cottage with ancient beams, it stood on a hilltop overlooking a heath and fields. It had three bedrooms and a ‘sunroom’ where the grandchildren could camp out. Within a reasonable distance of London, it became a convenient family weekend and holiday bolt-hole for many years. Sybil even had visions of making it their permanent home while they continued to work in London. They got to know the local people, and when Sybil heard that £600 was needed to repair the church tower at nearby Stansted, she gave a recital to raise the money. ‘She came in flowing robes, and held us absolutely spellbound for two hours,’ one villager remembered.”

The Parish Notes for July 1952, written by the Rev R.G. Coulson, record, “Our thanks are due to … and to Dame Sybil Thorndike for her recital of poetry at Tonbridge which brought in the handsome sum of £43 7s 6d after paying all the (quite heavy) expenses. The Recital was an unforgettable experience. It is very seldom that one has the privilege of hearing a great artist perform a perfect work of art, and we owe Dame Sybil deep thanks, not only for helping us so materially with the money but what is infinitely more valuable for giving us an extremely rare aesthetic treat. And all on her only free evening of the week!”

A footpath at the side of Cedar Cottage leads to Stansted by way of Coldharbour, where Colonel Alfred Wintle and his wife Dora lived. In his autobiography, Col Wintle recalls his neighbours in 1955: “One wet and miserable day, I invited to Coldharbour for lunch, Dame Sybil Thorndike, Sir Lewis Casson and Mays. Next to my wife, they were my stoutest supporters. The rain was coming down in torrents, and it occurred to me that they might have decided not to come after all. But the bell rang, I walked to the front door, and there was Dame Sybil. I’m not sure whether she was seventy-seven or eighty-three at the time, but there she was, bless her, with a kind of transparent tarpaulin over her head, a sturdy Macintosh covering most of her and Wellington boots to boot. In her arms, she clutched two useful-looking bottles. She was singing at the top of her voice….’ I’m singing in the rain, I’m singing in the rain, what a glorious feeling, I’m happy again…’ She had just walked through two miles of mud. I welcomed her, enquired after her health – a superfluous question, as she was always a picture of health and vigour – and then asked where Lewis was. “He won’t be long,” she replied. “He was repairing the roof when I left.” You see, one of the tiles has gone awry, and this dreadful rain might get through. He won’t be long, my dear.’ I’m not sure whether Sir Lewis was seventy-seven or eighty-two at the time, but between them, this magnificent pair has a joint age of around 160. Sir Lewis came along shortly, and he thought it nothing out of the ordinary to have been working at the top of a 42-rung ladder in the pouring rain. That’s the way to live your life – at the beginning, in the middle and at the end.”

Jonathan Croall wrote of this time, “In her offstage role as grandmother, she enjoyed weekends in the Kent countryside, taking the grandchildren on adventurous outings. ‘We had a jolly weekend at Cedar”, she told John in 1950. ‘Jane, Diana and I did one of my awful walks when we all came home bleeding from scratches and brambles! Great fun.’ She and Lewis would take long walks along the Lanes and across the hills, she striding a little way ahead of him. One local man recalled, ‘They would learn their lines as they went, and stop and admire the animals, which she loved, especially the pigs and cows. They invited us into their cottage, where she would sit on one side of the fire and he on the other. You never had to talk; she did all the talking. He’d fall asleep and she’d say, ‘Look at Lewis, what is he doing?!’ A woman who let Sybil and her family use their swimming pool remembers the first time she saw her famous neighbour: ‘She was standing on the garage roof, saying how beautiful the view of the pool was, and reciting Shakespeare.’

Sybil continued to have success in such plays as N. C. Hunter’s ‘Waters of the Moon’ at the Haymarket in 1951–52. She also undertook tours of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

Croall writes, “On their return to England [from a tour of Australia, New Zealand and a holiday in Canada in 1957/8] she experienced a rare black moment, brought on by Lewis’ depression and a visit to Cedar Cottage. ‘It left us both suicidal,’ she told John. ‘The garden was a wilderness and the house looked dark and boring…I have not had such a depression for years, and I wanted to pack up and go off on the boat to Australia, where we never felt that sort of depression… As for Lewis, he was in Hell’s own depression. His eyes are too bad to risk driving, besides his deafness and age. In his own work, he is only 60, but cars, cottages, any sort of responsibility, and he’s 83 at once.’ She wondered about getting a smallish house in Chelsea. John suggested they sell the cottage and simply enjoy living at Swan Court, and a year later, they did so. She and Lewis now sold Cedar Cottage, in about 1960. ‘I feel the most enormous weight off me,’ she admitted to John. ‘It’s a new start we will all be making.’ With the rent at Swan Court suddenly increasing substantially, she wondered if they should consider a move.” Lewis’ health at this stage was failing rapidly.

In 1962, Dame Sybil played again with Laurence Olivier in Uncle Vanya at Chichester. She made her farewell appearance with her husband in a London revival of Arsenic and Old Lace at the Vaudeville Theatre in 1966.

Her last stage performance was at the Thorndike Theatre in Leatherhead, Surrey, in ‘There Was an Old Woman’ in 1969, the year her husband Lewis Casson sadly died.

The Thorndike Theatre, now known as the Leatherhead Theatre, is a Grade II listed building in Leatherhead, Surrey. Roderick Ham designed the theatre for Hazel Vincent Wallace within the shell of the disused 1930s Crescent Cinema. The building also included a studio theatre, the Casson Room, for smaller-scale performances. Named after Dame Sybil Thorndike, the theatre was opened on 17 September 1969 by Princess Margaret.

The theatre closed in 1997 after the loss of public funding. A charitable trust was set up to operate it, and the theatre re-opened in 2001, with seating reduced to 495 plus three wheelchair places.

Her final acting appearance was in the TV drama ‘The Great Inimitable Mr Dickens’, starring Anthony Hopkins, in 1970. That same year, she was made a Companion of Honour. She and her husband, who was knighted in 1945, were one of the few couples who both held titles in their own right. She was also awarded an honorary degree from the University of Manchester in 1922 and an honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of Oxford in 1966.

Always a healthy, vigorous woman, she died of a heart attack on June 9, 1976, at the age of 93. She was survived by four children and a number of grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Dame Sybil’s ashes are buried in Westminster Abbey.

The following video interview was made in October 1969, the year of Sybil Thorndike’s last stage performance at the Thorndike Theatre in Leatherhead, Surrey, in ‘There Was an Old Woman’, a play by John Graham. Sybil was aged 87 when this interview was filmed.

Author: Dick Hogbin, Tony Piper

Editor: Tony Piper

Acknowledgements:John Oxley Library, Queensland. “Sybil Thorndike – A Star of Life” by Jonathan Croall. Wikipedia.

Last Updated: 08 November 2025