South Ash Manor

South Ash Manor, Ash Lane, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN15 7EN.

Grade II* listed (Historic England Ref: 1275615)

The manor house is now owned by and situated within the confines of the London Golf Club. It is accessed via the golf club entrance from Stansted Lane, which is 0.8 miles south of the village of Ash. The main house lies on the boundary of the Parishes of Ash-Cum-Ridley (Sevenoaks District) and Stansted (Tonbridge and Malling District). Historical accounts indicate that three local parishes intersected at South Ash Manor before boundary changes, the third being a detached area of the parish of Kemsing.

South Ash Manorhouse is a tall 15th-century timber-framed house with vertical half-timbering and plaster infilling, built on stone foundations possibly dating back to the 12th century. It has a hipped roof and is two storeys high with attics above. There are two gabled dormer windows, five other windows, two small casement windows with small squared leaded panes and five large sash windows with glazing bars intact on each ground and first floor. The two-storey porch is a later addition, with its first floor oversailing with ornamental timbering and a gable over. Red brick extensions are on the ground floor at each end of the building. The interior has some 16th-century painted dining room decorations and early 18th-century plain panelling. The house was built by the Hodsoll family, after whom the local hamlet of Hodsoll Street is named. There is also the possibility that a building existed on this site at the time of the Domesday Book.

The London Golf Club plans to substantially refurbish the manor house as a wedding venue, and below-ground archaeological studies are planned prior to work commencing. These may reveal further insights into the property’s origins.

Over the past ten years, the exterior and interior of the manor house have significantly deteriorated and are currently best described as dilapidated. The original gardens and lawns, which have been untended for longer, are now completely overgrown.

The photograph highlights the property’s condition in 2014, when it was last offered for sale. In 1998, planning consent was granted for using the manor house and barn as offices, and from this date until 2014, a structural engineering company, John Allen Associates, occupied the manor house and related buildings. Whilst the structure of the building was maintained, some of the internal heritage features and wall paintings have suffered.

The Manor House was last used as a family residence by Kenneth Kingston between 1947 and 1989. The following link provides a photo gallery containing images of the house and gardens from the 1989 sale particulars, highlighting their prime condition in the 20th century.

The London Golf Club is undertaking a significant project to develop the facilities to host premier international tournaments. These developments include a 240-room hotel, spa facilities, accommodation lodges, an equestrian centre, racquet sports facilities, a new driving range, and an Elite Performance Centre. As part of this significant development, the manor house and associated buildings will be refurbished as a heritage wedding venue. The History Society is working with Selby Projects, the developers, to facilitate future public access to the manor house and promote its history and that of the surrounding area.

Section I: Origins

Manors originated in Europe in the early Middle Ages, particularly after the fall of the Roman Empire, and became a central feature of the feudal system. They were self-sufficient communities, often based around a manor house and a large area of land, with the lord of the manor at the top of the social hierarchy and peasants at the bottom. The manorial system was a way of organising land ownership, labour, and society, with the lord providing land and protection in exchange for loyalty and service from their tenants.

The following extract from Frank Proudfoot’s book ‘A Downland Parish – Ash by Wrotham in Former Times’ by W. Frank Proudfoot [Ref 2] suggests the following regarding the origins of South Ash Manor.

“In the mid-thirteenth century, one Thomas de Aesse, otherwise Ash, held a fourth part of a knight’s fee in the parish which pertained to the manor of Kemsing, of which latter the lords were Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and Eleanor his wife. Kemsing Manor formerly belonged to William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and de Montfort’s interest arose from his marriage to Eleanor, Pembroke’s widow. She was also Henry III’s sister, a relationship which did not prevent her new husband from becoming the King’s most rebellious subject. Thomas of Ash’s fee must, it is suggested, have been the nucleus of the estate for which John de Southesse paid two marks for the two parts of a fee at the knighting of the Black Prince and which was to become known as the manor of South Ash. It was recorded on that occasion that previously the same John de Southesse had held from the manor of Kemsing and that manor from the Earl of Leicester. At the time, the Kemsing manor was held by Sir Otho de Grandison, whose uncle of the same name had acquired it many years before.”

The Norman Conquest of 1066 formalised and institutionalised the manorial system, making manors a key part of the feudal structure. Manors were the primary administrative units of land ownership, with lords providing protection and managing the estate, while tenants provided labour and resources.

A manor house was historically the primary residence of the lord of the manor and the administrative centre of a manor. Manor houses often included a great hall where manorial courts, communal meals with manorial tenants, and lavish banquets were held.

The British Museum holds the earliest records relating to the manor of South Ash in the form of a charter bearing the reference B.M. Add Ch 16459, dated 1 November 1310, during the reign of King Edward II. The charter establishes John de Southesshe as the owner of the lands in the parishes of Stansted, Kemsing, and Ash and Lord of the Manor of South Ash.

Unfortunately, much of the parchment’s text has faded over the centuries and cannot be identified; in this case, the missing text is marked on the following transcript by ‘…’. Thanks go to Mrs. Zena Bamping of West Kingsdown for translating the document after viewing the original document in the British Museum.

“On the Feast of All Saints in the fourth year of the reign of King Edward son of Edward first after the Conquest John de Suth Essch..Margery de Peckham the said John has given & this present charter (confirms) to the aforesaid Margery all his manor of Suth Essehe with all its appurtances…..and all other tenements that Agnes mother of the said John held in dower in the same manor from the heirs/the inheritance of the said John the day of completion…rent….suits of court Reliefs….& all other…parishes of Kemeseynges North Essc North Essche and Asscheherst elsewhere..now belonging without any reservation in the same place. Having and holding the said Margery all the said tenements with all their appurtances..with aforesaid tenements which the aforesaid Agnes held in dower as above written…..(of the chief) lord of that fee by services therefore owed & accustomed For ever and paying therefore per annum to the said John & Elena his wife plus a certain Margery de Pacham (and the heirs of) John and Elena lawfully begotton…twenty pounds sterling paying at Easter ten pounds & at Michaelmas ten pounds for all services…. the said John and Elena auit of court to the heirs of the same John…said tenements..belonging For ever And the said John and Elena & the heirs (and assigns) warrant to the same Margery and their heirs & whoever their assigns all the tenements above written with their appurtances..royal suits & services therefore owed For ever in witness whereof both aforesaid John & Elena & aforesaid Margery This charter cyrographate…completed their seal alternatively affixed These being witnesses Sir Adam de Chivenyng William de Croyr & William de Chelesfend..John de Chymberham William de Chymberham Richard de Stansted clerk Achard de Aldeham John Soninord junior William de Eyneford Henry (Fremolyn) (one more name) Richard Eyncheman Ralph Freymolyn Richard Bryn & others Given at Aldeham on the feast of All Saints the year above written”.

In his book ‘The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 2’, Edward Hasted [1], suggests the family took its name from South Ash and that the manor was taxed at a rate that showed it was considered half the size necessary to provide income to keep a knight comfortably. The following is an extract from the section on the Parish of Ash.

“Adjoining to Ridley, westward, lies Ash, called in the Textus Roffensis, Æisce; and in Domesday, Eisse. Ash is situated on high ground among the hills. The soil of it is mostly chalk, and the greatest part of it unfertile, and much covered with flints. It contains about three thousand acres of land, of which about six hundred are wood. It has about eighty houses and four hundred inhabitants. There are two hamlets in it, Hodsoll Street and West Yoke. At the north-east boundary of it is Idley farm, belonging to Thomas Coventry, esq. of North Cray. It is shaped very irregularly, and bounds to no less than nine parishes. The church stands by itself, nearly in the centre of the parish, and about a mile southward from it, the manor and hamlet of South Ash. On the eastern side of the parish, on the decline of the hill, towards the valley, it is covered with coppice wood. It is not much frequented, and has nothing further worth mention in it.

At the time of taking the general survey of Domesday, this place was part of the possessions of Odo, bishop of Baieux, the king’s half brother. On the disgrace of bishop Odo, about the year 1084, the king seized all his lands and possessions, after which this place was granted to Hubert de Burgh, earl of Kent.

In the reign of King Henry III, this parish seems to have been separated into three different manors, one of which, being the most capital, was called the MANOR OF ASH, alias NORTH ASH, and in that reign was in the possession of Henry Pencombe.

The Manor of South Ash, the hamlet situated about a mile southward from Ash church, was formerly held by a family who took their name from it. In the 20th year of King Edward III, John de Southesshe was owner of it and then paid aid for it, as two parts of a knight’s fee, holding it of the manor of Kemsing and Seal, as that was again of the earl of Leicester.

After this family was extinct here, it came into the possession of the Huddysholes. William Huddyshole, alias Hudsoll, possessed it in the reigns of Henry V. and VI. Mr. John Huddyshole was owner of it in the reign of King Henry VII and was succeeded in it by his son of the same name, as he was by his son, Mr. William Hodsoll, gent, who died in 1585, and lies buried in this church, as do many of his descendants. The Hodsolls bear for their arms, Azure, a fess wavy, betw. three stone sountains or wells argent, which fess was not borne antiently by them. Philipott supposes that the three wells in their arms allude to the name of Halywell, or Holywell; perhaps they might take it from their being tenants to that priory, for their estate of Halywell in this parish. From Mr. William Hodsoll, this manor, as well as Hodsoll-street, in this parish, continued in an uninterrupted succession to his descendant, William Hodsoll, gent. of Dartford and South Ash, who died possessed of it in 1776, without issue, and by his will devised them (after his widow’s decease) to his cousin, Mr. Charles Hodsoll, of Ash, who is the present possessor of them.

There is a court still held for this manor, which is within the liberty of the duchy of Lancaster.”

To summarise, the manor came into the possession of the Huddyshole family in 1390. The Huddyshole family substantially developed the property during the late 14th century, with William Huddyshole recorded as the owner during the reigns of Henry V and VI (1413-1471). The Manor continued in the possession of this family, with uninterrupted succession to William Hodsoll, of Dartford and South Ash, who died childless in 1776. The Manor was left to his wife, and when she died, to William’s nephew, Charles Hodsoll.

Several members of the Huddyshole family are buried in Ash Church, and by this time, the family name had settled as Hodsoll. The Hodsoll family coat of arms included three white wells, which are thought to relate to the holy well situated just to the north of the village green in Hodsoll Street. The site is now the Holywell Residential Home.

To summarise, the manor came into the possession of the Huddyshole family in 1390 and remained with the Hodsolls for more than four hundred years.

Section II: Boundaries & Parishes

The division of Kentish land into Lathes and Hundreds dates back to Saxon times but was not fully established until the thirteenth century. Each hundred consisted of several parishes grouped together with a ‘court’ or meeting place where the inhabitants dealt with routine judicial, security and tenancy matters. The grouping of hundreds into lathes was for judicial purposes; the justices travelled around the lathe every three months to deal with more serious issues.

Historically, parishes were loosely defined groupings of manors, hamlets, and other residences. Ancient parishes are often described as ones which existed before the 1597 and 1601 Elizabethan Poor Law Acts. They frequently had detached parts that were not contiguous with the rest of the parish, and in other cases, an entire parish was in a detached part of the county to which it belonged. Parishes were exclusively ecclesiastical until the mid-19th century, when the 1866 Poor Law Amendment Act defined the concept of civil parishes.

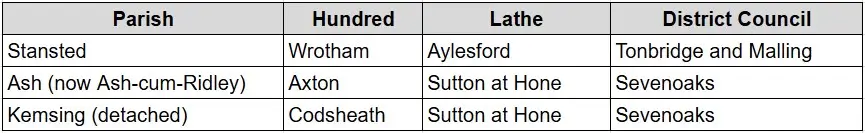

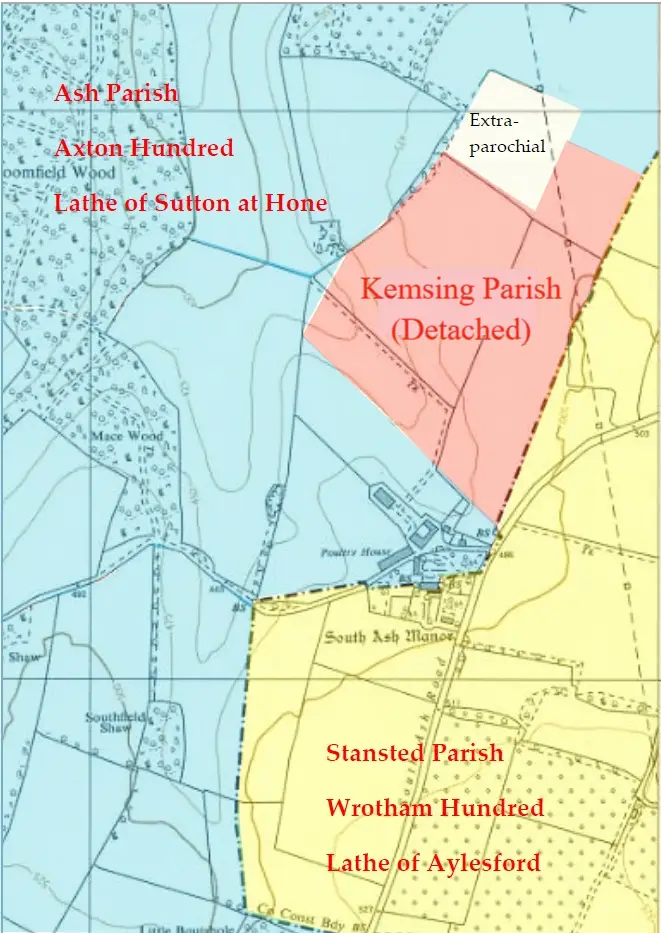

Historically, the lands forming the Manor of South Ash were in three parishes: Ash, Stansted, and a detached area of Kemsing parish. Illustration L3080-25 is an extract from a mid-20th-century Ordnance Survey map annotated to show how South Ash Manor stands on an ancient administrative boundary that separated the parishes and highlights the relevant ‘hundreds’ and ‘lathes’.

Historically, the same boundary separated the hundreds of Axton and Wrotham (Ash was in Axton hundred, and Stansted was in Wrotham hundred). A hundred consisted of a group of parishes, so each county would contain several hundreds. The word hundred, and the system’s origin, is obscure, but by the 11th century, hundreds had become established as a unit of organisation, including taxation. They survived for various purposes until the end of the 19th century. The same parish and hundred boundary was also contiguous with the lathe boundary, a lathe being a specifically Kentish layer of administration, and an addition to the hundred system, possibly dating as early as the 6th century.

The following table highlights the old and modern civil units of governance relating to South Ash Manor. Hundreds and Lathes have ceased to exist; the modern hierarchy ascends from Parishes to Districts and Counties.

There is a local peculiarity in that in the late 19th century, a detached portion of the parish of Kemsing existed within Ash parish, a short way to the north of South Ash Manor house. Kemsing was in the hundred of Codsheath, thereby introducing a third element of hundred-level regional control to the landholding of South Ash Manor. A parcel of land at the northern end of the detached area was extra-parochial, meaning it did not fall within the jurisdiction of any parish. Detached parts of parishes are not uncommon, and the extra-parochial regions are not unknown. They could arise for various reasons, sometimes in cases where a manor or estate physically crossed a parish boundary, or where a manorial holding in one parish was associated with another parish. Both reasons may apply in the case of South Ash Manor.

South Ash Manor was originally held of Kemsing and Seal Manor, in Kemsing parish, which was held of the Earl of Leicester in the 14th century. By the 19th century, the parcel of land within Kemsing parish had shrunk northwards, away from the manor house, as shown in Ordnance Survey maps. The detached part of Kemsing parish is now part of Ash parish.

The boundary most likely ran through the manor house in the 16th century for the reasons explained below. Speculatively, either the manorial holding or the parish of Kemsing (or both) may once have extended some way to the south in the more distant past. Illustration XXX shows a large old half-buried stone built into the wall beside the original doorway within the porch of the manor house. This is likely a parish boundary marker between Stansted and the original detached part of Kemsing parish, which was incorporated into the building when the manor house was originally built. The order of events is uncertain, but South Ash Manor certainly had a close and deliberate relationship with the longstanding administrative boundary on which it is sited.

Ecclesiastical records would support the view that the detached part of the parish of Kemsing originally extended southward as far as the South Ash Manor house, making a credible manorial estate with the manor house placed centrally between the extracted parish of Kemsing and Stansted parish.

Dr Paul Lee, in his thesis ‘Monastic and secular religion and devotional reading in late medieval Dartford and West Kent’ [Ref 3], provides records from the Rochester consistory court held on 26 July 1564. Dr Lee confirms that the following notes were taken from the record rather than transcription, and that no significant details were omitted. The original record combines English and Latin with surnames spelt as they appear in the original court papers.

“JOHN FREMLING of Kemsing, where he was born a yeoman of about 60 years, was examined on a matter exhibited by Richard Tebold of Kemsing. He deposed that the kitchen and the old hall of South Ash, as it was labelled 40 years previously, were within the parish of Kemsing. Further, he said that about 47 years ago, he was hired by the clerk of Ash to be the “Saynt Nicholas Bisshopp” for the parish of Ash. This clerk came to Fremling’s father’s house in Kemsing and took young John to the mansion house of South Ash. There they found one Markley, then a farmer, sitting on the high bench of the hall of the said mansion. The clerk told Markley, “I have brought this boye that shalbe bisshop of Asshe”. Markley took John Fremling by the hand, sat him down on the bench, and said, “Remember a nother day that thou sittest nowe in the parishe of Kemsing”. To the second article put to him, Fremling said he remembered that “old Hodsoll”, an old ancestor of William Hodsoll, with his wife, his man and his maid, did yearly at Easter or before, receive the sacrament at Kemsing parish church. Further about 20 years ago, one Burrowe, the farmer of South Ash did receive the sacrament at Easter at Kemsing parishioner as a parishioner of it. Fremling stated that he knew William Hodsoll, immediately after the death of his father, did cause two elms growing within his “churche marke” of Kemsing to be lopped and received money for the lops from the son of John (BLANK) of Kemsing. Fremling remembered hearing his father say on one occasion that there was a farmer dwelling in the mansion house of South Ash, having a man and a maid who went to Ash church to be married. The parson of Ash refused to marry them, so they were constrained to go to Kemsing parish church.

THOMAS HILLES of Kemsing, a yeoman born in that parish, who was aged around 49 years, was examined on the same matter exhibited by Richard Tebold, gentleman of Kemsing. He said that the west end of the house at South Ash was in Kemsing parish.

WILLIAM FREMLING, yeoman of Kemsing, where he was born, aged about 46, was examined as above and stated that he had heard that his ancestors said half the manor of South Ash was in Kemsing.

JOHN MUNKE an approximately 50 year old yeoman of Kemsing, where he had lived for ten years having been born at Worth in Sussex, stated that he had heard that from the “high dyes or benche in the hall of South Ash unto the end of the kitchen of the same” was in the parish of Kemsing. He had heard that the inhabitants and ancestors of William Hodsoll dwelling in the manor of South Ash did yearly like to receive the sacrament at Easter in Kemsing parish church.

JOHN MILLER a husbandman of Kemsing where he had lived for seven years, having previously lived at Hadlow for three years and before that at Horton (i.e. Kirby) where he was born, aged about 43 years, he had heard that the greater part of the mansion of South Ash was in Kemsing and that the inhabitants of the manor were counted as parishioners of Kemsing.”

The Fulljames survey of the Parish of Ash, published in 1792 [Ref 5], contains detailed Tithe maps of Ash parish and a description of the parish boundaries titled ‘A Perambulation of the Parish’. The text includes an interesting paragraph describing how the Ash, Kemsing, and Stansted parishes intersected in South Ash Manor’s kitchen. The following is a direct extract from the Fulljames survey:

“… continues up the Lane to the Corner of South Ash Farm Yard and then across the Stack-Yard to the North-East Corner of Pigeon-house, leaving that to the South as well as some part of the House, there being a Post in the Kitchen where the Parishes of Ash, Stanstead and Kemsyng meet, the part of House &c not in Ash are described on Plan by a dotted Line, The Bounds then goes from Corner of House in a direct line across the Orchard to the Gate, then crosses Lane to a Gate in Six Acre Field and from thence to the South-East Corner of Maggotty hill, and then the Bounds go Southward in a direct Line across South Field.”

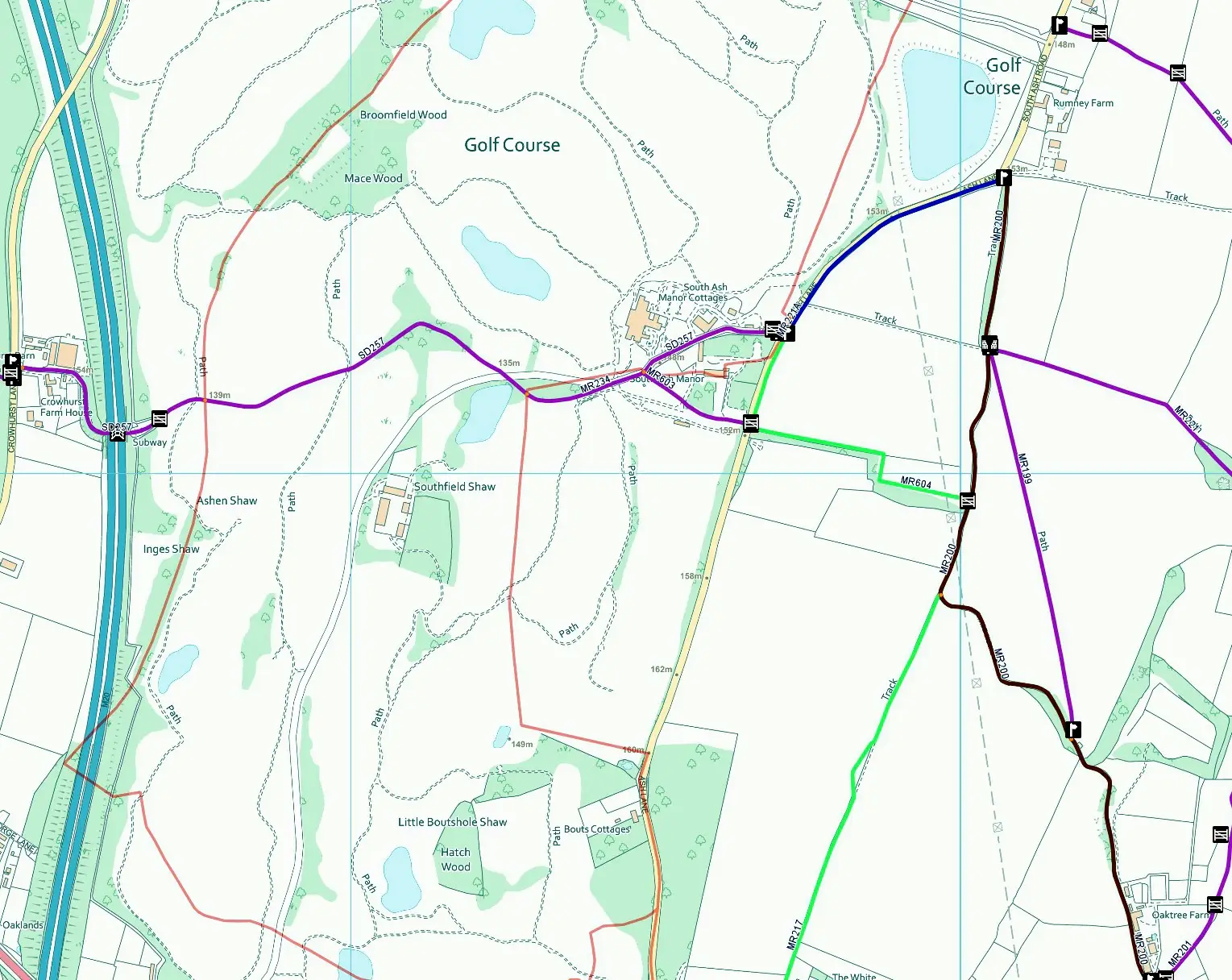

South Ash Manor was originally approached directly from South Ash Road, and a track shown on the tithe map of Ash ran westward through the landholding to connect with Crowhurst Farm. Crowhurst Farm consisted of some 130 acres of farmland adjacent to the land associated with South Ash Farm. The Hodsoll family, the then owners of South Ash Manor, purchased Crowhurst Farm in the 17th century. In the early 1830s, the Hodsoll family became bankrupt, and South Ash Manor and Crowhurst Farm were sold to London wine merchants John and William Wild. The land that originally formed Crowhurst Farm is now physically cut off from the golf course by the modern M20 motorway. The old footpath and private horse road that ran from South Ash Manor to Crowhurst Farmhouse still exists as a public footpath across the golf course and under the motorway. Other than that, the two areas of ancient farmland, which were farmed as one area at some stages in their history, are now entirely separate from each other.

The original entrance to South Ash Manor from South Ash Road, which is currently marked by a fine set of metal gates, is no longer in use. The manor house is now accessed via the main entrance to the London Golf Club in Stansted Lane. The new access road passes the main clubhouse and continues to the manor house.

Tithe maps suggest that the mid-19th-century extent of the landholding associated with South Ash Manor Farm was defined mainly on the east side by South Ash Road and on the south side by Stansted Lane. To the west, the edge of the manorial holding followed a series of hedges and shaws northward from

Stansted Lane to Mace Wood, which is still named on modern maps. The northern part of the landholding extended into the detached portion of Kemsing parish, and into a roughly triangular field called Wind Valleys to the north-west of the detached part of Kemsing. The 19th-century extent of the farm was much larger than the apparent original estate, and when sold in 1832, the farm consisted of 380 acres. Less than a decade later, that figure had fallen to 297 acres by the time of the tithe apportionments, suggesting that the landholding was reduced by about a fifth during the 1830s.

Two footpaths run westward from South Ash Lane on either side of the main manor house. Footpath SD257 is in Ash parish and runs for a short distance just to the south of South Ash Manor cottages, finishing to the east of the manor house and south of the golf clubhouse, where it merges with footpath MR603. Footpath MR603 is 194 metres long and starts on Ash Lane from a metal gate 100 metres from the end of Bridleway MR604. The path runs west, south of the manor house and joins footpath SD257. Footpaths SD257 and MR603 merge and continue westward across the golf course as footpath MR234. A small section of this path is within Stansted Parish. It runs for 203m to a point near the Golf Course lake, where it once again crosses the Parish boundary into Ash-cum-Ridley and continues west as SD257, passing under the M20 motorway to Crowhurst Farm and on towards West Kingsdown.

Note: This website’s ‘Environment’ section provides detailed information on the footpaths in Stansted parish.

Kenneth Kingston purchased the manor house and the surrounding farmland associated with South Ash Farm in 1947 and lived and farmed there until 1989. Subsequently, the home and farmland were sold to a Japanese consortium to develop the London Golf Club. The London Golf Club continued to purchase additional parcels of land along its current boundary with Stansted Lane, which now extends to some 700 acres. Historically, South Ash Farm has never extended east of South Ash Road.

As part of a significant development of the golf club and facilities, the club owners have acquired additional land east of South Ash Lane, which was part of Parsonage Farm. This additional area is planned to be used as a new driving range and Elite performance centre, with an underpass being built to connect these facilities to the clubhouse, the hotel and other new developments.

Note: A brief history of the London Golf Club and details of the future planned developments are available in Section VI: The London Golf Club.

Section III: The Chapel of St James

Whilst old maps or tithe drawings do not show a chapel or building in the manor house grounds, church records suggest that one existed there in the 16th century and that the building was subsequently converted and used as a dovecote.

In his thesis ‘Monastic and secular religion and devotional reading in late medieval Dartford and West Kent’ [Ref 3], Dr Paul Lee notes that the lack of coincidence of parish with manorial borders gave some parishioners freedom of manoeuvre. While the lords promoted their religious initiatives to recruit support from the inhabitants, this may have provided extra facilities for worship on the parish boundaries.

Dr Lee notes that the existence of a chapel at South Ash Manor is recorded in a case heard in the Rochester consistory court in 1564. Thomas Kettyll, a sixty-two-year-old farmer of the parish of Ash, testified that a dove-house in the manor used to be a chapel of St. James, and it was the vicar and clerk of Kemsing who celebrated mass and service there on St. James’ Day.

The following is an extract from the court proceedings (Rochester consistory court dispositions CKS DRb/Jdl ff142-143r, 149v-151r):

“Thomas Kettyll, a sixty-two-year-old husbandman (a farmer) of the parish of Ash, testified that a dove-house in the manor used to be a chapel of St. James, and it was the vicar and clerk of Kemsing who celebrated mass and service there on St. James’ Day (25th July). Kettyll himself had been used to assist the priest on a number of occasions. Thomas Burrowe, a husbandman of Ash, aged forty years, remembered that his father annually paid 8d to the clerk of Kemsing during matins and mass on St. James’ Day, and he continued to pay 4d to the clerk of Kemsing after services ceased in the chapel.”

Dr Lee surmises: “It appears from this that the chapel was staffed by Kemsing parish. In this case, manorial influence confused their sense of parochial loyalty to the extent that some did not even know which parish they lived in. These details of festival masses in the chapel and the continuing tradition of the boy bishop, however, suggest a picture of flourishing traditional religion before the Reformation, in this rural area, finding expression in parish churches and manorial chapels, depending on where one lived.”

The exact location of the chapel is unknown. Local history articles by Leslie Morgan, published on the website of St. Peter & St. Paul Church, Ash, suggest that the chapel was situated at the South Ash Road end of the estate, close to the manor house. Referring to tithe maps, two parcels of land on the east side of South Ash Road are named Upper and Lower Chapel Croft and could provide a connection. Evidence may be below ground, but confirmation would require significant archaeological effort to determine this.

Section IV: The Manor House

Historic buildings are classified in grades to show their relative importance:

Grade I – buildings of exceptional interest.

Grade II* – particularly important buildings of more than special interest.

Grade II – buildings of special interest warranting preservation

The earliest entry for South Ash Manor in the National Heritage List is dated 1 August 1952 (Entry Number: 1236122) and shows it within Stansted Parish (Tonbridge and Malling District). A second and later listing is dated 1 June 1967 (Entry Number: 1275615) and shows it within Ash Parish (Sevenoaks District). South Ash Manor is categorised as Grade II*.

List Entry Number: 1275615

Date Listed: 01-Jun-1967

South Ash Manor TQ 56 SE 6/25 1.6.67 II* 2. On the common boundary of the Parishes of Ash-Cum-Ridley (Sevenoaks District) and Stansted (Tonbridge and Malling District), previously listed in Stansted Parish on 1 August 1952. Tall C16 timber-framed house with vertical half-timbering and plaster infilling, built on stone foundations of the C12. Hipped tiled roof. Two storeys and attics. Two gabled dormers. Five windows. Two small casement windows with small squared leaded panes and five large sash windows with glazing bars intact on each of the ground and first floors. Two-storeyed porch, probably later than the main building, with its first floor oversailing, ornamental timbering and a gable over. Flanking the doorway on the ground floor are carved grotesque wooden figures, which are modern insertions, but the door is original. Ground floor addition in red brick at each end. The back is faced with red brick. The interior has some C16 painted decoration in the dining room and some early C18 plain panelling. The house was built by the Hodsoll family (after whom the hamlet of Hodsoll Street is named), who retained it until the C19.

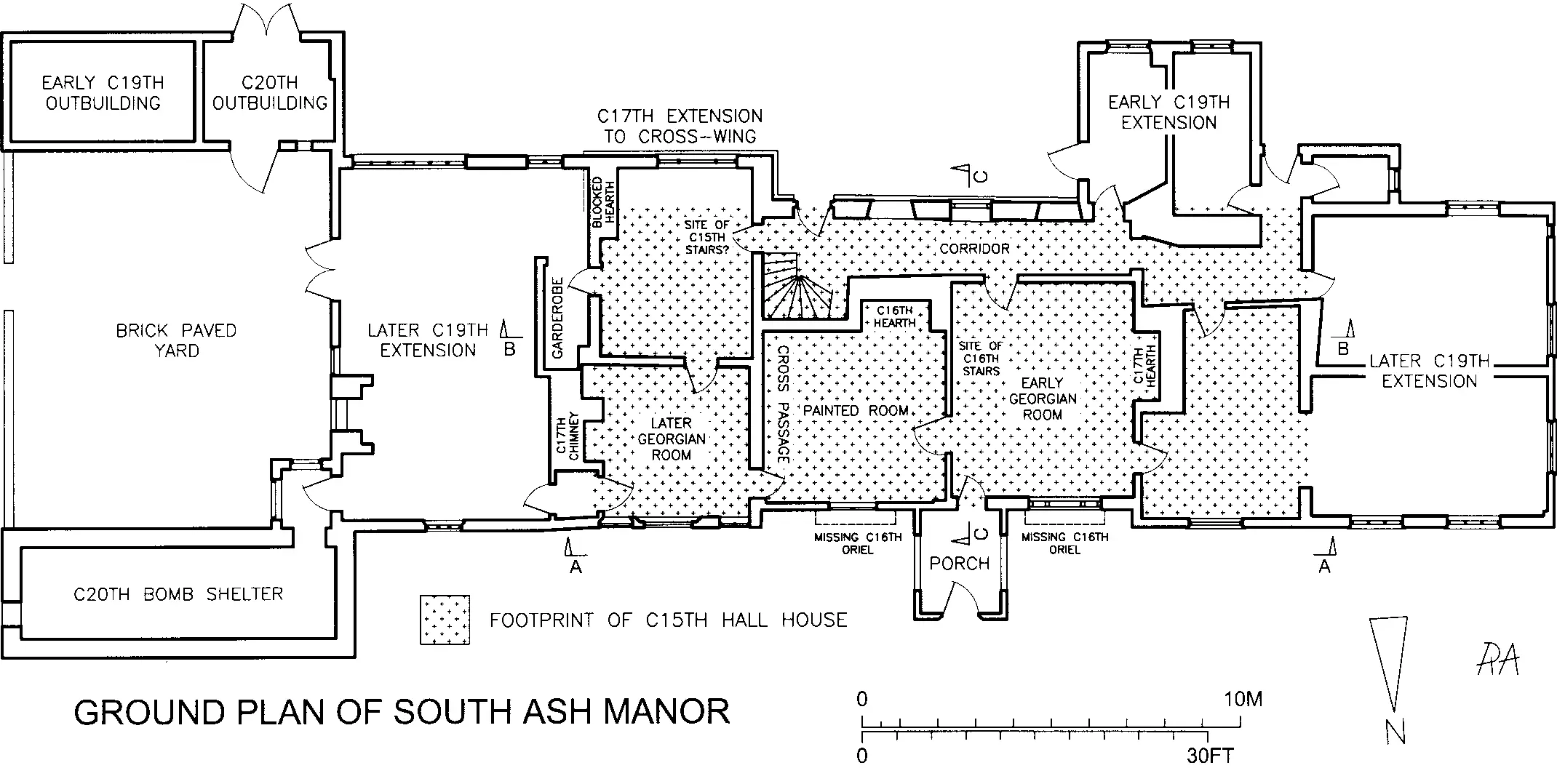

The house is a large and impressive timber-framed building with cross-wings, a two-storey porch and a former open hall, dating almost certainly to the 15th century. In its original form, South Ash Manor comprised a low two-bay open hall flanked east and west by taller two-storey cross-wings. This double-ended arrangement created an ‘H’ shaped building in plan, the jettied upper floors of the contemporary cross-wings projecting forward of the face of the hall. The original bays of the open hall and its roof have now been almost entirely rebuilt.

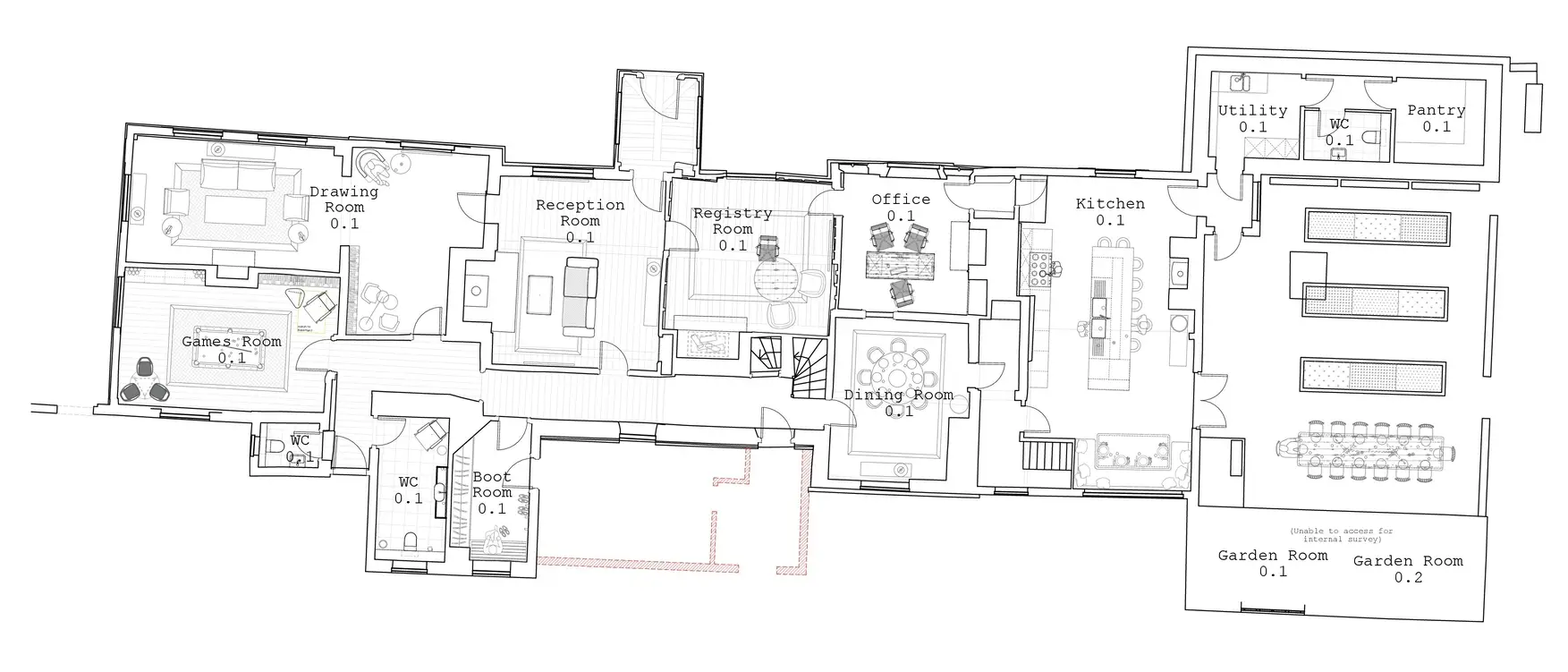

The floor plan illustration highlights the footprint of the original 15th-century hall house and the subsequent conversions and extensions. The manor house has been modified, enlarged and refashioned several times since it was first built. Modifications include the insertion of a first floor in the hall in two stages, the west bay, then the east bay, including the addition of a staircase, the rebuilding of the north front of the hall in the 16th century, the addition of wall paintings, mainly in the ground floor room in the east bay of the former hall, also in the 16th century, remodelling and alterations to the cross-wings, the addition of a two storey porch in c.1600, and the raising of the hall and its roof to make a true upper storey, and the reconstruction of the rear wall in brick.

The earliest house for which there is current evidence consisted of the surviving eastern and western wings and a hall, no longer existing, where the central section of the present house now stands. The smoke-blackened rafters, which have been reused in certain parts of the central section roof, point to such an earlier hall, open from ground to roof level, with a central fireplace but no chimney or flue. Traces of service doorways in the eastern cross-wing support this view as these would have given access to the wing from a cross-passage, sited within the earlier hall.

There is no record of a house at South Ash Manor at the time of the Domesday Book (1086), and no evidence of a previous building has been found above ground. The Historic England Listing suggests that the house was built on stone foundations dating back to the 12th century, and archaeological surveys undertaken in 1998 [Ref 4] and 2001 [Ref 7] reached similar conclusions. The London Golf Club are considering further below-ground archaeological surveys before the planned refurbishment work to the manor house is undertaken, and these may give more insight into the property’s medieval origins.

A timber-framed two-story porch is set centrally at the front (north) of the central section of the house. The upper storey is a jettied construction with dragon beams and has a jettied gable at the front. All the porch walls are close-studded, except for the upper front and the gable, which have square framing with a pattern of quarter-round braces.

From a construction perspective, the porch is not a part of the original house. It is held against the front wall by a pair of iron straps nailed to the wall plates, which turn at right angles to pass around posts within the wall of the house. At ground level, the porch gives access to the west ground-floor room. The first-floor level has doors to both the east and west rooms.

There are very few local examples of similar two-storey porches. One is at Lynsted Court, near Sittingbourne, listed as being built in the early 16th century, and another is at The Old Cottage, Bickley Road, Bromley, where the nearby brick gate arch bears the date 1599. The South Ash example was likely built soon after the central section of the house, before 1650. “The Porch Chamber” is also mentioned in the 1699 inventory of the then-owner, William Hodsoll.

As part of the Heritage Report produced by HCUK [Ref 6], Dr Andy Moir of Tree Ring Services was engaged to investigate the building. Unfortunately, the majority of samples failed to date, but Dr Moir was able to conclude as follows:

“Due to a lack of surviving or accessible timbers, together with very few timbers containing more than 40 rings, the dendrochronological potential to date most of the earliest elements of South Ash Manor, including the hall and both wings, was assessed as very poor. Samples taken from the earliest timbers in the hall, the east wing, the west wing and the porch, all failed to date. Two precise felling dates in the winter of 1559/60 provide evidence for a rebuild of the front of the hall in 1560, or soon after, while three samples dated from the west wing provide evidence for an extension at the rear occurring in 1590, or soon after.”

Although the dendrochronology survey did not make progress on the early dating of the hall and cross-wings, it helped date the rebuilding of the front of the hall to 1560 or shortly afterwards.

The extensive landscaped gardens and orchards that existed when Kenneth Kingston sold the property in 1989 have mainly disappeared and are now completely overgrown. A proportion of the original grounds was repurposed when the golf course and clubhouse were built. Based on the sales particulars, the following gallery contains photographs of the house and gardens from when the manor house was last used as a residential property in 1989. Photo Gallery

In summary, the historical timeline for the manor house is as follows:

- 1500 to 1540. Construction of open hall house with central fireplace, cross passage at the east end and cross-wings to east and west.

- 1600 to 1640. Demolition (or destruction) of the hall and replacement by a new floored-in central section with a brick chimney stack.

- 1600 to 1650. Construction of 2 two-storey porch at the front of the house. Fire / structural failure at the rear of the house and rebuilding in brick.

- Late 17th century. Widening of the front windows on both floors of the east wing.

- Later 18th century. Possible division of the large ground floor hall into two rooms. Panelling of the western and possibly the eastern ground-floor room. Framing and new plastering of all rooms, except where panelled. New sash windows at the front of the house, new doors, etc. Kitchen extension and cellar at the south end of the east wing.

- Early 19th century. Extension at the south end of the west wing.

- Late 19th century: Construction of the western cellar, further single-storey ranges at the house’s east and west ends, and the introduction of the present staircase.

- Early 20th century. Construction of a conservatory to the rear with reused timbers from the farm. Note: The conservatory will be removed as part of the planned refurbishments.

Medieval Carved Figures

Photographic evidence from the 1920s shows two carved figures placed upon wooden supports, on either side of the entrance porch. In archaeological terms, they are residual, so cannot be regarded as being of high integrity for dating the building as a whole. However, there are no other buildings of c.1300 in the vicinity, so the figures are likely to have been associated with the early history of the manor.

Dr Moir’s dendrochronology survey [Ref 6] included analysing a sample from the carved figures, which produced a felling date suggesting they were likely to have been carved between 1282 and 1314. This date range interestingly includes the year when South Ash Manor was first mentioned in the original Charter of 1310. These observations would indicate that they are of significant age and historical value, and the Society recommends that further specialist analysis of the figures be conducted to confirm the likely period during which they were created.

Whilst it is conjecture, the carved figures may represent the original Lord of the Manor, John de Suth Essch, and his wife, Elena, given that the suggested carving dates align with the establishment of South Ash Manor in 1310.

The Society has suggested to the London Golf Club that the two carved figures be professionally cleaned, restored, preserved, and placed on display in a protected environment within the manor house to support access for public viewing.

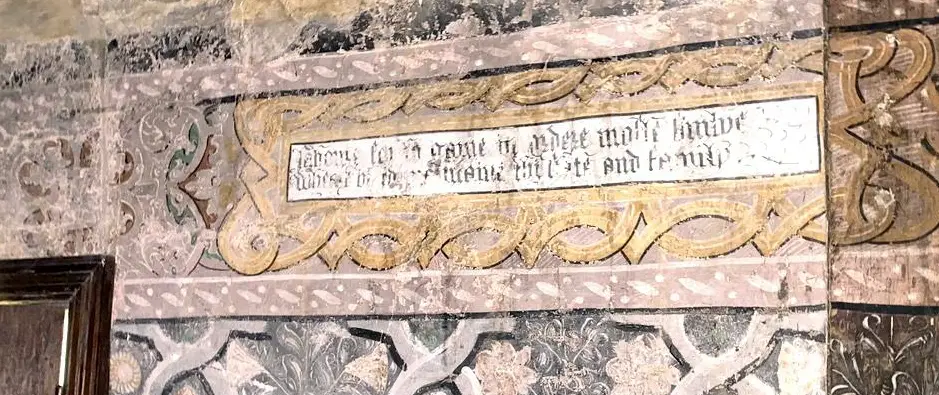

Wall Paintings

At ground level, the east bay of the hall features a collection of what are believed to be Elizabethan wall paintings. This room was used as a dining room when the property was last occupied as a residential home. The wall decorations include several inscriptions, including strapwork and floral forms. The paintings extend over much of the room, covering the chimney breast and the rebuilt façade.

Following the use of the manor house as offices and further neglect over the past thirty years, the wall paintings have further deteriorated, and additional consideration is needed as to how best to protect the remaining images for the future.

In January 2024, HCUK [Ref 6] invited Dr Kathryn Davies, a heritage specialist and visiting fellow of Oxford University, to study the wall paintings at South Ash Manor. The Society is grateful for Dr Davies’s insights, which are as follows:

“The painting scheme follows the typical late sixteenth/early seventeenth century arrangement of frieze and central panel, but there is no sign of a skirting or dado. This is not unusual as these are very vulnerable, and it may have been lost. The painting covers the brick stack, wattle and daub panels and timbers alike, where timbers have survived since the late sixteenth century, including a nailed-up door. This may, or may not, have fallen out of use before the painting was done. It was usual to paint doors as part of the pattern. The pattern has no relationship with the substrate.

Painting survives on three walls, north, south and east, mainly on the upper portions of the walls. The painting comprises a frieze of black letter texts in text boxes alternating with a complex strapwork design. The texts have not been deciphered but will most likely be godly texts reinforcing the new religion. The frieze is separated from the main panel by a simple band with a diagonal dash and dot design like a simplified guilloche band. The main panel comprises a simpler strapwork design with floral motifs. Unusually, the frieze has an additional upper band separating it from a further section of frieze of arabesque work.

The texts are in English. Despite damaged and missing letters, they can still be read in part, apparently being typical moral observations of the period set out in rhyming couplets. In other words, the texts were homespun exhortations from the head of the family to impress guests, educate children, and encourage servants, particularly those who could read fluently in English.

Further paintings of broadly similar date and type are on the upper floor of the building, but these appear to be simpler and without texts. The wall paintings are clearly an important feature of the building and are of considerable artistic significance. They are rare, but are not unique in buildings of this date and type.”

In a survey undertaken in 1998 by the Fawkham & Ash Archaeological Group [Ref 4], Roger Cockett notes the following:

“A particular feature of the eastern room is the painted plaster decoration of interlaced straps, flowers and foliage, which survives on the upper parts of its west and south walls, but not on the wall adjoining the west room. Its condition is now very fragile, with the paint and the plaster base having deteriorated for some time. It is reported that this room was, for many years, also lined with panelling like its neighbour, the ground-floor western room, and that the paintings were only revealed after its removal.”

The painted decorations include three narrow oblong panels, each containing two lines of verse. The illustration shows the one in the best condition when photographed as part of the 2024 HCUK survey. Although indistinct in many places, it has been transcribed as follows:

Laboure for to gaine in ordere moste simlye

Wherei bi to maintaine thi state and family

This is essentially moral or didactic advice encouraging one to work diligently and modestly, earn a living straightforwardly and adequately, and support oneself and one’s family. A word-by-word explanation is as follows:

- ‘Laboure for to gaine’ – Work (labour) to gain (earn or acquire).

- ‘in ordere moste simlye’ – Most simply or honestly (orderly and modestly).

- ‘Wherei bi’ – Whereby (by which means).

- ‘to maintaine thi state and family’ – To sustain your condition (status, livelihood) and your family.

Applying these explanations produces a modern English translation as follows:

Work to earn honestly and simply,

By which you may support your position (or livelihood) and family.

Section V: Ownership History

1310 to 1390 – John de Southesshe

In the mid-thirteenth century, Thomas de Aesse (Ash) held land equivalent to a fourth part of a knight’s fee in the parish that pertained to the manor of Kemsing. The lords of Kemsing were Simon de Montfort (Earl of Leicester) and his wife Eleanor (the sister of Henry III). Eleanor had previously married William Marshal (Earl of Pembroke), who owned Kemsing Manor.

The small amount of land belonging to Thomas of Ash (one quarter of the land which could support a Knight’s expenses) was likely the nucleus of the estate for which John de Southesse later paid two marks at the knighting of the Black Prince. By then, the land amounted to half a Knight’s fee and became known as the manor of South Ash. It was recorded that the same John de Southesse had previously held the manor of Kemsing from the Earl of Leicester.

The British Museum holds the earliest records relating to the manor of South Ash in the form of a charter, dated 1 November 1310 (during the reign of King Edward II). The charter establishes John de Southesshe as the owner of the lands in the parishes of Stansted, Kemsing, and Ash and Lord of the Manor of South Ash.

Whilst there is no definitive evidence of a building or house on the site at this time, archaeological studies undertaken in 1998 (Ref 4) and 2001 (Ref 7) suggest that the current manor house may have replaced an earlier stone dwelling. The Historic England National Heritage listing also indicates that the current building was built on stone foundations dating to the 12th century.

The Southesshe family died out in the late 14th century when the Hodeshole (Hodsoll) family took ownership of the manor and associated farmland.

1390 to 1831 – The Hodsoll Family

South Ash Manor came into the possession of the Hodsoll family sometime during the late 14th century. John Hodeshole’s death was recorded at South Ash in 1385, and his grandson, William Hodsoll (1395 – 1455), is considered instrumental in building the original manor hall-house. This was in the 15th century when William was recorded as the owner during the reigns of Henry V and VI (1413-1471).

The origins of the Hodsoll family can be traced to the village of Fawkham, in Kent, where John Hodesole’s father, Thomas de Hodeshole, was born in 1300, and his grandfather, Clement de Hodesole, was recorded as being born in Fawkham in 1280. The old English names of ‘Huddysole’ and ‘Hodshole’ gave rise to the surname ‘Hodsoll’ adopted in subsequent centuries.

Historical references to significant Hodsoll family members can be found in the areas surrounding Ash, including the parishes of Stansted, Wrotham, Ightham, Kemsing, and Plaxtol. Through marriage in the 16th century, a second significant branch of the Hodsoll family centred on Cowfold, in Sussex.

With the advent of transatlantic sea travel in the 17th century, members of the Cowfold branch of the Hodsoll family emigrated to America, with Bennett Hodsoll recorded as arriving in 1635, just 15 years after the Pilgrim Fathers first set foot in New England. In his book ‘The Hadsell-Hodsoll Genealogy’, published in 1956, Willard L Hadsell (Ref 8) researched the origins of the American ‘Hadsell’ family and traced their roots to the Hodsolls of Ash. Willard Hadsell travelled to England in 1954 and visited various churches and locations in the parishes surrounding Ash to establish further details on his Hodsoll ancestors.

The local hamlet of Hodsoll Street, in Ash-cum-Ridley is likely named after the family. The photograph shows the Green Man public house in Hodsoll Street in 1919. It was a popular local pub, but unfortunately, it was destroyed by fire in June 2021. A campaign was launched to rebuild the pub, and plans have been submitted.

The Manor continued in the possession of the Hodsoll family for some four centuries. Notable members of the Hodsoll family from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries lie beneath the stone slab memorials in the Hodsoll Chapel of St Peter and St Paul Church in Ash. A photographic gallery of the eleven memorial slabs can be viewed by selecting the following link:

Hodsoll Memorials at Ash Church.

The Hodsolls were gentleman farmers and, as Lords of the Manor, were significant community members. Notable family members relating to South Ash Manor were: John Hodsoll, who inherited the estate in 1663 and was a captain in the merchant navy. One of John’s sons, James (died 1710), was commander of HMS Squirrel in the Royal Navy. William, who inherited the estate in 1740, was a tanner in Dartford and a famous early Kent cricketer who played for England.

One of the bedrooms at the manor house is historically referred to as ‘The Captain’s Room’. James Hodsoll reputedly had the honour of rowing the then king, Charles II, on a ceremonial visit to the Fleet. To commemorate this event, he painted a picture depicting the scene, which used to hang on the wall of his room at South Ash Manor.

The Hodsoll family had an uninterrupted line of ownership/possession for over four centuries to Charles Hodsoll, who was confirmed to reside at South Ash Manor in the Fulljames survey 1792 (Ref 8). Charles Hodsoll’s son William [8] is the last member of the Hodsoll family to be associated with ownership of the Manor.

In 1770, William Hodsoll [7] Gent., owned the Manor of South Ash, and when he died in 1778, he left everything to his cousin, Mr Charles Hodsoll of Ash. In 1831, following poor harvests and financial difficulties, the following particulars of sale of the Manor and farmland, sold ‘with the concurrence of the mortgagees of Mr Hodsoll’ and comprising four farms totalling 577 acres, named South Ash, Little Ash, Crowhurst in Kingsdown, and Bakers Farm in Stansted, were advertised.

The unfortunate conclusion of the Hodsoll family’s involvement at South Ash came on January 26th, 1847, when an advertisement for a sale by auction of ‘Valuable Modern Household Furniture and Effects at South Ash Farm by order of the assignee of William Hodsoll, a bankrupt’.

1831 to 1926 – The Wild Family

It is currently unclear whether the Hodsoll estate was purchased as one or whether the various farms were sold to different parties. The 1841 Census confirms that John and William Wild, a family of London vintners, owned South Ash Manor. It was, however, occupied and presumably leased to William Hodsoll, who appears in the 1841 census as a farmer living at South Ash Farm House. As recorded in the census, two households were probably divided between the manor house and the Grade II listed building, South Ash Manor Farm Cottages. The principal household consisted of William Hodsoll and his wife Ann, five children and an elderly father. The secondary household was headed by Sarah Kettel, aged 80, possibly related to Thomas Ketyll mentioned in the earlier account of the Chapel of St James, in the 16th century. She was in charge of a governess for the children, three female servants, and four agricultural workers.

South Ash Manor remained in the hands of the Wild family into the early 20th century, when the Wild family had taken up residence, supplanting the Hodsolls. The 1901 census shows the owner as Robert Lewis Wild, but living at Hurstmonceaux, Sussex. In the 1911 census, the principal building was called South Ash House, and occupied by Charles Hillary Wild, who was recorded as ‘of independent means’. Charles Wild was a Major in the Royal West Kent Regiment and was the grandson of William J Wild (1794 – 1869), who originally purchased South Ash Manor in 1832.

The photograph shows South Ash Manor in 1924 and features, left to right, Reginald Hillary Wild (1910-1938), Vera Angela Wild née Verney-Cave (1881-1952), Major Charles Hillary Wild, seated (1880-1954), and Charles Edric Verney Wild (1906-1986).

Major Charles Wild lived with his wife, two young sons, and four servants in 21 rooms. Two cottages at the farm were occupied by James Stevens, a waggoner (household of seven people living in four rooms) and Spencer Ewen, a farm bailiff (household of four people living in six rooms). Charles Hillary Wild was the son of Charles Augustus Wild of Tansor Court, Northamptonshire. He married the Hon. Vera Angela Verney-Cave, daughter of Lord and Lady Braye of Stanford Hall, Leicestershire, in 1905.

The 1921 census for South Ash Manor records continued occupation by Charles Hillary Wild, who lived with his wife and two servants in 16 rooms. Two cottages at the farm were occupied by James Fowler, a shepherd with a household of five people living in six rooms, and Olive Stevens, widow of James Stevens and a household of five people living in four rooms.

In 1924, Major Wild placed the estate on the market, stipulating that unless sold as a single lot, he would retain the Lordship. In the event, the land and buildings were sold to Mr George E Leavey and the Lordship was retained by Major Wild.

At the time of the emergency census taken on the outbreak of war in 1939, South Ash Manor was occupied by Mr Leavey, whose wife had died in 1935. He was described as a ‘mixed farmer and director of a public engineering company [‘Smith and Nephew’]. He lived there with one of his two sons, a housekeeper (whom he later married) and three domestic servants. His two sons were Dennis and Tony. Both joined the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards; both were in active action throughout the war and were in Normandy after D-Day, where Dennis sadly was killed in action. Tony survived and went on to become a successful businessman and Member of Parliament.

There were four households in the four farm cottages, including what is now a single building, namely Mr. Walter Grimmer (a chauffeur/mechanic living with his wife, daughter and two other people), Mr. Henry Rogers (a horseman on the farm with his wife, son and two others), Mr. Charles Stevens (a farm labourer living with his wife), and Mr. John Ball (a groom living with his wife).

The sale of the physical assets to Mr Leavey led to the separation of the physical estate and the title of Lord of the Manor. The lordship of the manor was subsequently purchased at auction by Mr Leslie Morgan and continued entirely separately from the land.

In 1947, just after the end of World War II, the estate changed hands again. It was purchased by Mr Kenneth Kingston, who continued to use it as a farm for over 40 years. There are several newspaper reports relating to Mr Kingston winning pig farming and agricultural prizes in the 1960s. During his tenure as custodian of the manor house, the gardens were developed to a very high standard, and the house became a beautiful and comfortable residence. Mr Kingston’s grandson, David Lindsay, says, “In 1988/89, my grandfather was almost 80 years old and was ready to retire as a farmer. The family was advised that, in order to sell the farm, it would be best to sell the house and farm together. At that time, nobody wanted land, but houses were in high demand. A developer bought the house and farm and then sold it to a Japanese consortium, which went on to develop the London Golf Club.”

This heralded the end of 700 years of farming on the estate, with the Manor House at its hub. The London Golf Club secured planning consent for a change of use and developed a 36-hole golf course and clubhouse, which was opened in 1993.

In 1997, the Golf Club initiated a renovation project to bring the Manor House back into use, related to the golf club, and appointed John Allen Consulting Engineers to lead the project. The works contract commenced in October 1997 but was halted soon after, as it became apparent that the cost of the works would exceed the sale value of the renovated property. The un-renovated property was put up for sale in January 1988. John Allen Ltd was seeking a new corporate headquarters and decided that the Manor House was the ideal property. Thus it was that the property was purchased and used as offices until 2015.

In 2015, the Manor house was purchased by the London Golf Club, which, by this time, was itself under new ownership. Between the ten years it ceased to be used as offices and the date of this article (2025), the property has remained vacant.

The London Golf Club are planning to develop the Manor House and related buildings as a wedding venue as part of their ‘London Project’, details of which are included in the following sections.

Section VI: The London Golf Club

The London Golf Club now covers an area of some 700 acres and comprises two 18-hole championship courses, the International and the Heritage.

The Japanese businessman Masao Nagahara led a consortium that initially developed the golf club in response to a perceived need for a world-class golf course near London, purportedly with the support of Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of the UK from 1979 to 1990. Although the club was initially opened in September 1993 by Sir Denis Thatcher, the official course opening was in July 1994. A charity skins match marked the occasion on the Heritage course between three all-time greats of golf: Tony Jacklin, Seve Ballesteros and the course designer Jack Nicklaus.

The London Golf Club’s ownership changed in 2003 when it was purchased by the Bendinat group, which also owns the Royal Bendinat Golf Club in Mallorca. Since that purchase, the club has hosted numerous tournaments on the European Senior Tour.

In 2018, private American investors purchased the golf club, and Morningstar Golf & Hospitality now manages it on their behalf. Morningstar is an American company that operates golf clubs and courses in over 25 U.S. states, the UK, Europe, and Japan.

In August 2024, a public consultation was launched regarding the club’s plans to transform it into a world-class leisure destination, the first of its kind in Kent. The overarching aim is to create a venue capable of hosting events on a global scale.

The ‘London Project’ involves a new hotel and spa with 240 rooms at the forefront of planned developments, and 80 luxurious lodges are also intended to provide additional accommodation. The new centrepiece of the club’s sport and leisure offering will be ‘The Pavilion’, an ultra-modern hub with a restaurant, retail outlet, gym and creche. Facilities will include racket sports, equestrian facilities and a wild swimming lake. As well as leisure, the project will offer educational benefits to the local community through the proposed ‘Sports Turf Academy’, comprising training facilities, a workshop and classrooms. A new driving range and an Elite Performance Centre will be located east of Ash Lane, along with associated parking and landscaping.

Along with these significant improvements and developments, the manor house, the adjacent stables block, the barn, and the two sets of cottages will be developed into a notable wedding venue.

The History Society is liaising with Selby Projects, who are managing the project, to help preserve the manor house heritage, support public access to the building, and provide historical information and context to future visitors.

Section VII: Planned Developments

The London Golf Club has been granted planning permission to convert the Grade II* listed South Ash Manor and the adjacent stables block from office use to visitor accommodation as part of a project to develop a world-class wedding venue.

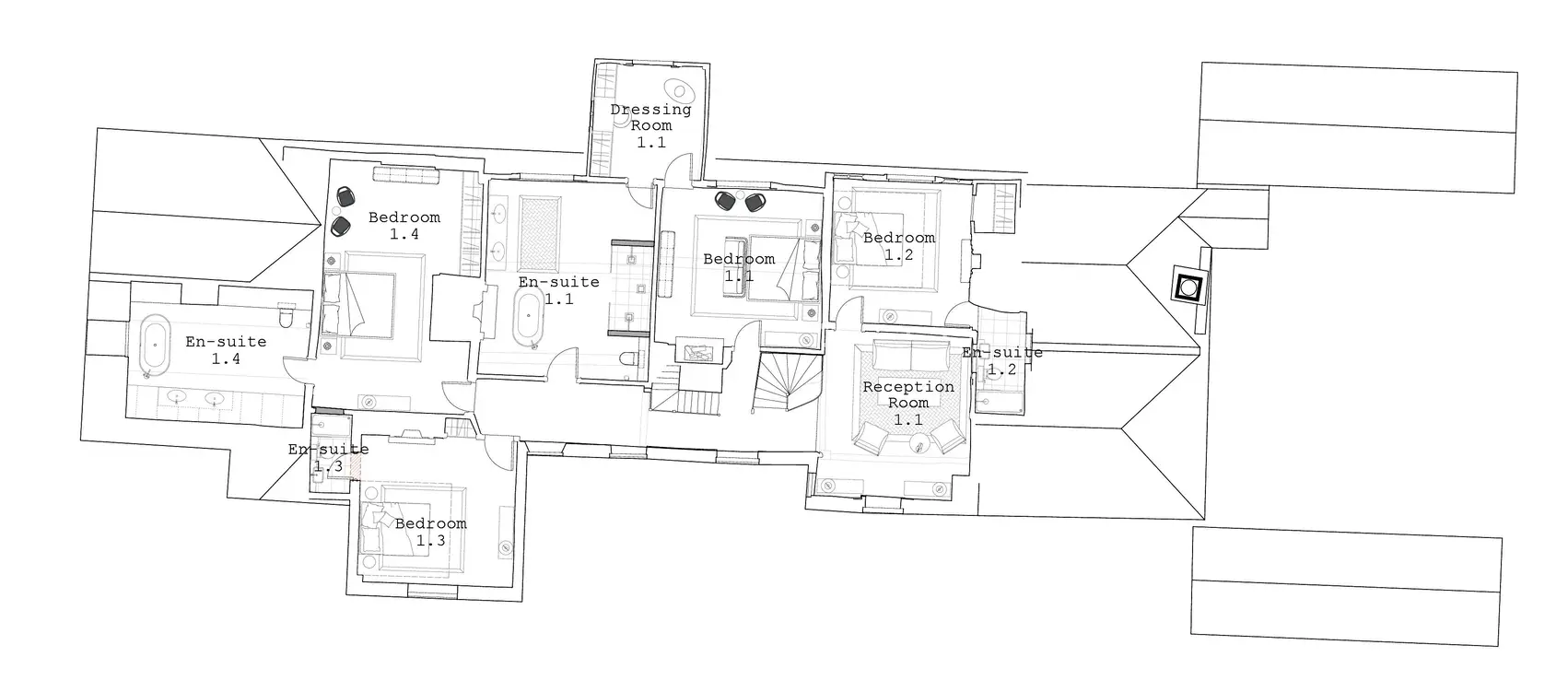

The proposed wedding complex is east of the main clubhouse in the northeast area of the golf club estate, bordering the northern boundary and Ash Road. South Ash Manor house will be substantially refurbished to form the central registry office with a bridal suite and additional wedding party en-suite bedrooms on the first floor.

South Ash Barn is northwest of the manor house and is planned to be converted and refurbished as the main wedding function room. The existing stable block, between the manor house and the barn, will be redeveloped as four luxury lodges for wedding guest accommodation. Further wedding guest accommodation will be provided in Kirby Cottages and South Ash Manor Farm Cottage.

Kirby Cottages have been unoccupied for many years and are in significantly poor condition. South Ash Farm Cottages were originally farm worker dwellings and numbered 3 and 4 Ash Road, with Kirby Cottages originally numbered 1 and 2.

South Ash Farm Cottages were Grade II listed in 1967 with the following description:

“C17 or earlier. Timber-framed building of 2 parallel ranges with thin framing and plaster infilling; the ground floor refaced with flints, red brick and grey headers. Hipped tiled roof. Two gabled dormers. Two casement windows. Simple right-hand cambered-headed doorcase.”

The London Golf Club substantially refurbished the manor farm cottages in 1993, reconfiguring the two cottages as a single residence. The property was then used as accommodation for the original Japanese owners when they were in the UK. Following changes in ownership, the property is now used as golf club staff accommodation and is planned to be repurposed as wedding guest accommodation.

In addition to developing the various buildings forming the wedding venue complex, parking for approximately eighty wedding guests will be provided in the northeast corner alongside Ash Road.

The conversion of the manor house and the associated wedding venue accommodation is due to start once planning consent has been granted for the significant growth and development of the golf club as part of ‘The London Project’.

Before the refurbishment work on the manor house starts, a series of further below-ground archaeological surveys are planned. The results will hopefully confirm whether an earlier building existed before the current manor house’s 14th-century origins.

South Ash Manor House

The following two illustrations show the proposed reconfiguration of South Ash Manor, with the ground floor serving as the central registry office and the first floor housing the bridal suites. The main entrance through the porch leads to the east and west rooms, which will be repurposed as a reception room and a registry office. The ground floor will also include a dining room and a drawing room.

The first floor will provide four en-suite bedrooms, with the master bedroom having a separate dressing room on the central porch’s upper floor.

Author: Tony Piper

Contributors: Dick Hogbin

Editor: Tony Piper

Acknowledgements: The London Golf Club, Selby Projects, HCUK Group, The National Portrait Gallery, Canterbury Archaeological Trust, Dr Kathryn Davies, Dr Andy Moir, Ted Connell, Hollaway Studios.

References:

1. Edward Hasted, Esq. F.R.S. and S.A. The History and Topographical Survey of Kent, 1793, 2nd Edition. Vol. 1–11. Canterbury: W. Bristow, 1797

2. A Downland Parish – Ash by Wrotham in Former Times by W. Frank Proudfoot.

3. Monastic and secular religion and devotional reading in late medieval Dartford and West Kent. Abstract of thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History at the University of Kent at Canterbury by Paul Lee, in September 1998.

4. Fawkham & Ash Archaeological Group, Survey of South Ash Manor House, 1998.

5. Fulljames Survey of Ash next Ridley, 1972 – by T. Fulljames and stored at the Medway Archives in Strood, Kent.

6. Heritage Impact Assessment Report (Ref 9455), Dr Jonathan Edis, HCUK Group, October 2024.

7. South Ash Manor – An Architectural Survey, Rupert Austin, Canterbury Archaeological Trust, March 2001

8. ‘For a Thousand Years, The Hadsell-Hodsoll Genealogy’ by Willard L. Hadsell, published in America in 1956.

Last Updated: 02 December 2025