WW1 Airfield

Shortly after the Millennium, dog walkers were often treated to the incongruous sight of a 40-tonne articulated lorry attempting a three-point turn around the War Memorial to the accompaniment of a plaintive request from the hapless driver along the lines of “Where’s the airport, Guv?”

It didn’t take long for villagers to realise that the introduction of SatNav was the underlying reason behind these regular occurrences, as a less than punctilious search for Stansted Airport could easily misdirect a foreign driver, and the recently erected sign at J5 on the M25 would reinforce the belief they were close to their destination when “Stansted” appeared just to the east of J4 on their display. A quick whiz down the M20, and hey presto, they were there, with the bonus that they were an hour early! Happy days! Although if the two tight turns by the Hilltop didn’t give them cause to question their whereabouts, the steep descent into the village would certainly have got them wondering, hence their perplexed expressions!

Neither was confusion limited to the roads: incredibly, for a brief period, even British Airways’ in-flight passenger moving map displays also showed an imminent landing on the wrong side of the Thames, resulting in Stansted being featured on national TV! Roxana Brammer, the Clerk of Stansted Parish Council in Kent, made the most of the error by highlighting the tourist attractions of the village.

“Tourists would enjoy themselves in Stansted,” she said. “We’ve got St Mary the Virgin church. That’s medieval. Worth a visit. And there are three pubs. And we’ve got a hotel – the Hilltop. They do bed and breakfast and Sunday lunches.”

So it is ironic that, despite its hilly location and the aeroplane’s preference for large flat unobstructed areas for take-offs and landings, according to the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust (ABCT), Stansted was in fact once home to an airfield in the earliest days of aviation!

It was in 2020, when out of the blue, the Parish Council were approached by ABCT, who advised that a 2nd Class Night Landing Ground existed in Stansted during WW1 and was officially known as Royal Flying Corps (RFC) Station South Ash (Wrotham). It was operational between 3/10/1916 & 15/5/1919 as part of a network of Home Defence aerodromes in Kent & Essex. Further, they wished to install a plaque to commemorate this fact and sought the Council’s help in determining a suitable site.

The Parish Council was understandably surprised, as no one was old enough to have had any direct recollection of anything like this existing, or of where it could have been. ABCT were unable to furnish photographs and was only able to quote from Air Ministry documents, which described “a 35-acre site some 4 miles from Fawkham Junction (Longfield Station) between Bakers Wood and Rumney Farm and encompassing a minimum take-off and landing run of 500 x 350 yards.”

Village elders were consulted, and gradually some sketchy information came to light.

Tom Brooker remembered his father, John, ploughing one of the fields in front of Rumney Farm and referring to it as the “Flying Field”, and Mike Goddings recalled a conversation with Fred Hohler in which Fred mentioned that his Uncle Craven had his own light aircraft between the wars and flew it from the surrounding fields.

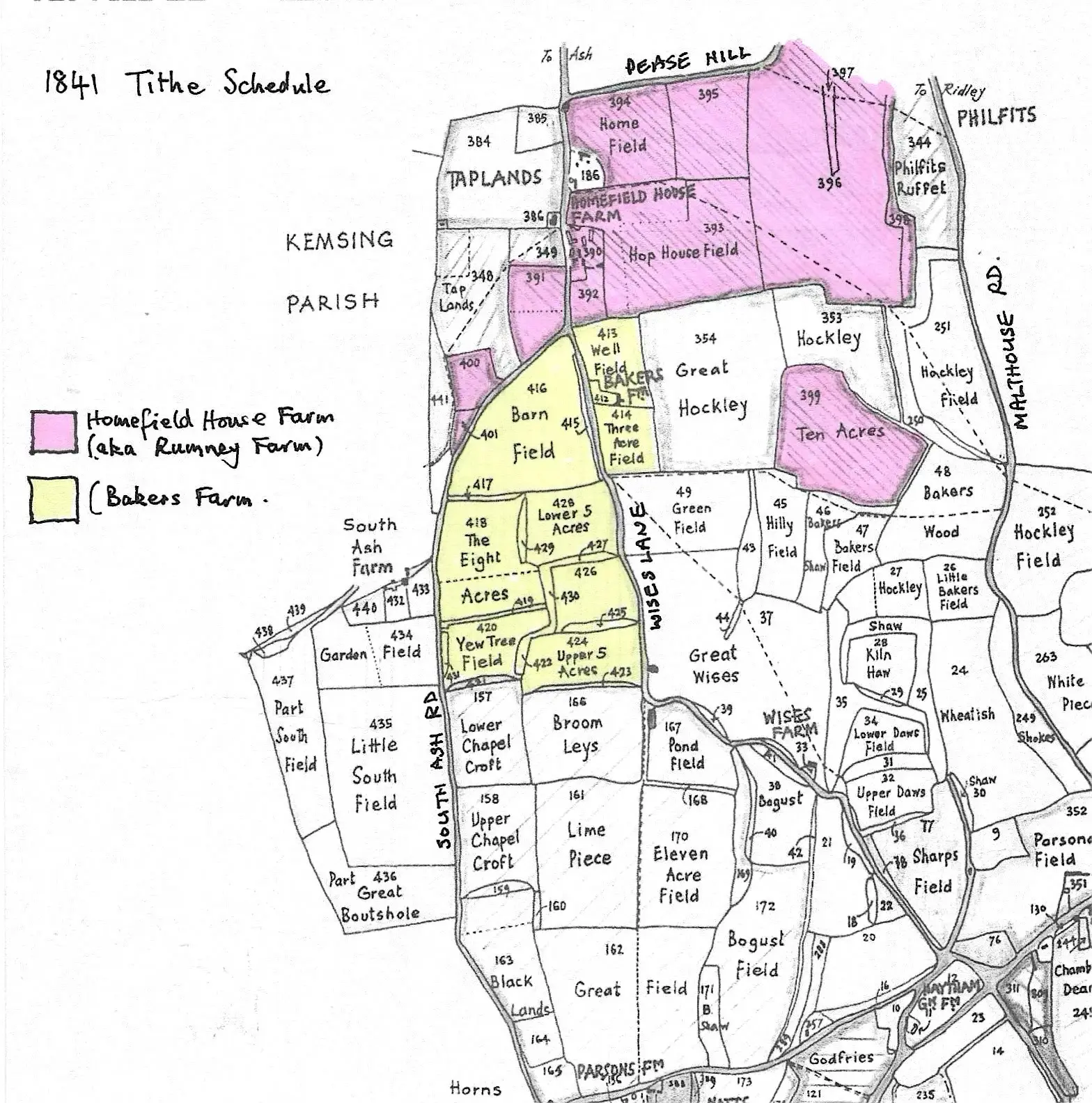

The 1841 Tithe Map shows three possibilities for the “Flying Field” based on the field boundaries that existed in 1841.

Rumney Farm was known as Homefield House Farm, and by WW1, Bakers Farm had ceased to exist. Between Homefield House (Rumney) Farm and Bakers Wood, the only flat fields are Great Hockley, Hop House Field and Home Field. At their eastern boundaries, the land falls away sharply to Bakers Wood/Malthouse Road, as does the land to the south of Great Hockley. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the “Flying Field” could have been any one, or a combination of any of these three fields.

That said, the Air Ministry dimensions of 35 acres/500 yards x 350 yards would rule out the possibility of just one field being used as the Landing Ground, as none are individually large enough: The Google Earth measuring tool shows that Great Hockley is 19 acres with a maximum length/width of 335 x 273 yards, Hop House is only 16 acres with a maximum length/width of 258 x 330 yards and Homefield is just 11 acres with a maximum length/width of 185 yards x 293 yards. (N.B. These measurements are slightly different from the area defined by the Tithe Map as they are based on the layouts since 1940, which exclude the residential curtilages of Homefield House (Rumney Farm) and the former Anchor & Hope PH. Consequently, the Landing Ground must have been created by merging some of these fields.

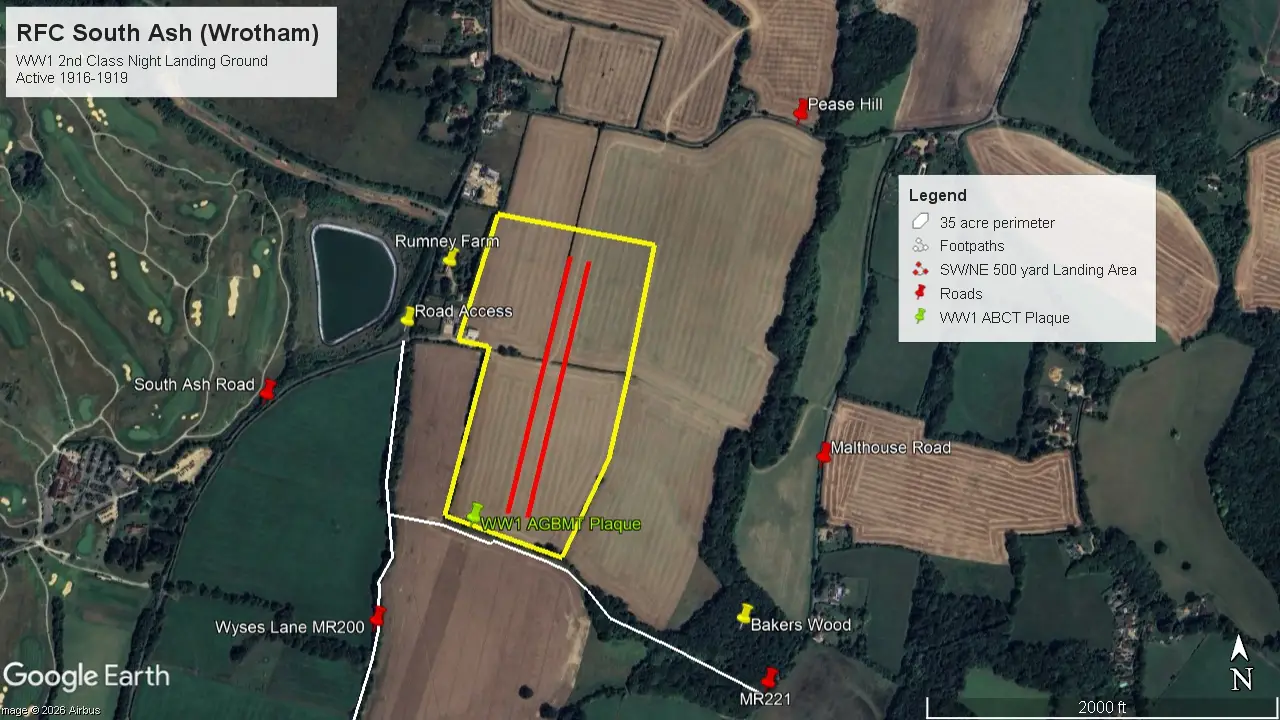

An obvious conclusion is that this would have been Great Hockley and Hop House Fields, as their combined area is exactly 35 acres and their combined dimensions represent a maximum length and width of approximately 598 yards and 330 yards respectively, i.e. somewhat longer but a bit shorter than the stated Air Ministry particulars. The satellite image shows what this would have looked like.

The area bounded by the yellow line is exactly 35 acres. The access road to the current industrial warehouses at the junction of Wyses Lane and South Ash Road is approximately 4 miles from Longfield station, whilst the two red parallel lines represent the take-off and landing minimum run of 500 yards into the prevailing wind direction. (N.B This predominant SW/NE directional runway alignment can also still be seen at the other North Downs airfields of Kenley, Biggin Hill, Romney Street and Rochester.)

Hence, there is a strong likelihood that Great Hockley and Hop House Fields were merged to form the Landing Ground and that the dividing hedgerow was either not planted at that time or was grubbed up to allow an uninterrupted landing run. The still obvious gaps in the mature trees on both southern boundaries would also have facilitated this. Interestingly, Hop House Field is now divided into two with the hedgerow following the take-off and landing direction.

In December 2021, a flint cairn and plaque were erected by Tom Brooker adjacent to the southern boundary alongside Footpath MR221.

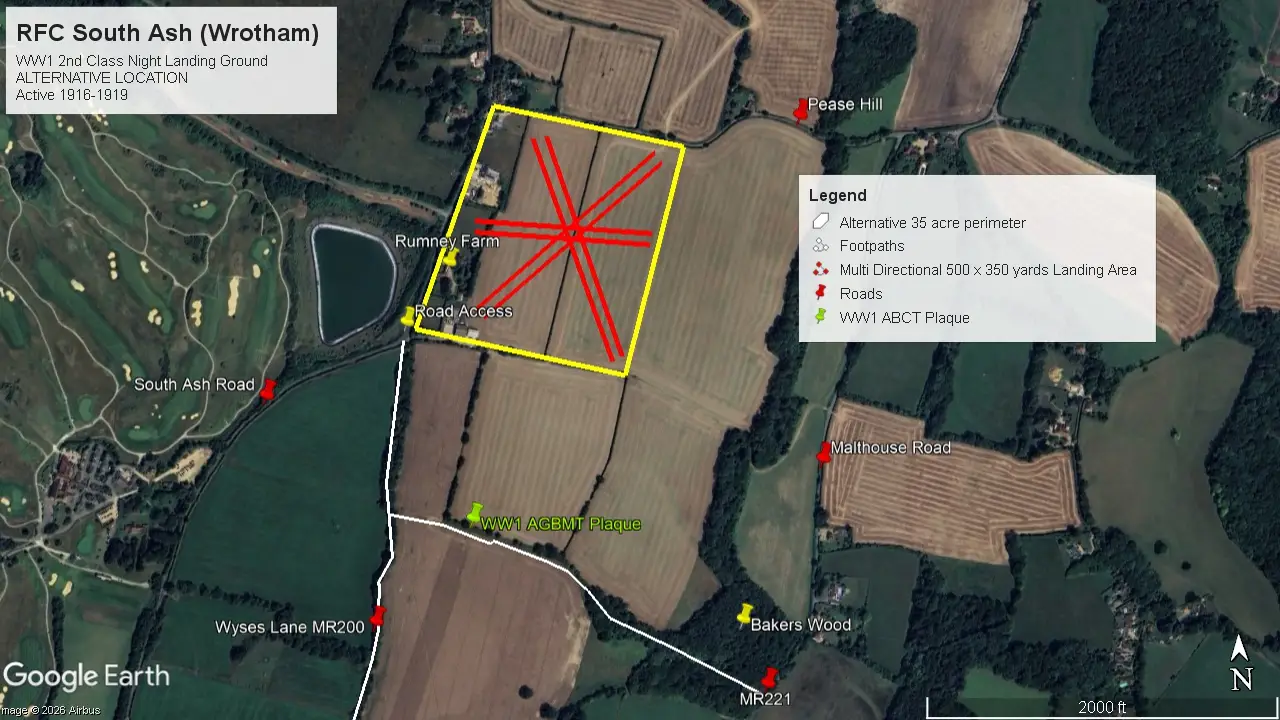

However, there is another possibility. By combining the Rumney Farm and former Anchor and Hope PH curtilages with both Hop House Field and Homefield, the Google Earth measuring tool also calculates this area as 35 acres. Moreover, the merger of Homefield with Hop House Field provides not only a SW/NE landing strip of 500 yards but also a similar-length strip in the SE/NW direction, and the increased width of 380 yards provides an E/W strip of 350 yards. This is evident in the satellite image.

In fact, were it not for the more recent division of Hop Field and the construction of the industrial units at the entrance road, it must be said that if a surveyor were looking to create a landing strip for light aircraft today, this would certainly be the preferable alternative.

If this were the location in WW1, the placement of the plaque along MR221 would be somewhat misleading, but then hindsight is a wonderfully exact science!

Regardless of its actual location, what exactly was the purpose of a 2nd Class Night Landing Ground in WW1 and what went on at RFC South Ash (Wrotham)?

Sadly, there are no specific references or accounts in published documents or books covering that period of history, beyond which units flew from there.

Whilst it is well known that Britain came under heavy aerial attack in WW2, it is perhaps less well known that this also happened in WW1, albeit on a much lesser scale. Although the main military activity was centred on the Western Front in France, Kent coastal towns came under attack from shelling, and from 1916, an increasing number of airborne attacks were made on London, the eastern coastal towns and the southeast from Airships (Zeppelins), and later Gotha and Giant aircraft based in Belgium. In this part of Kent, Swanley, Sevenoaks, Dartford, Rochester, Chatham, Tonbridge and Gillingham all suffered damage.

At that time, the Royal Air Force (RAF) had yet to come into existence, and Britain had two Air Arms: the RFC, commanded by the Army, which was responsible for repelling attacks over land, and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), commanded by the Senior Service and responsible for any attacks over the sea. It was these airborne attacks that forced both the RFC/RNAS to switch their focus in the UK from purely training to establishing a network of Home Defence units to counter this threat. They were supported by anti-aircraft guns around the major conurbations and military establishments, together with searchlights, as the attacks were increasingly made at night.

As a 2nd Class Night Landing Ground, South Ash only ever accommodated a single flight of two or three aircraft, with the other Squadron flights dispersed elsewhere. (The suffix of Wrotham was probably to prevent confusion with Ash near Canterbury.)

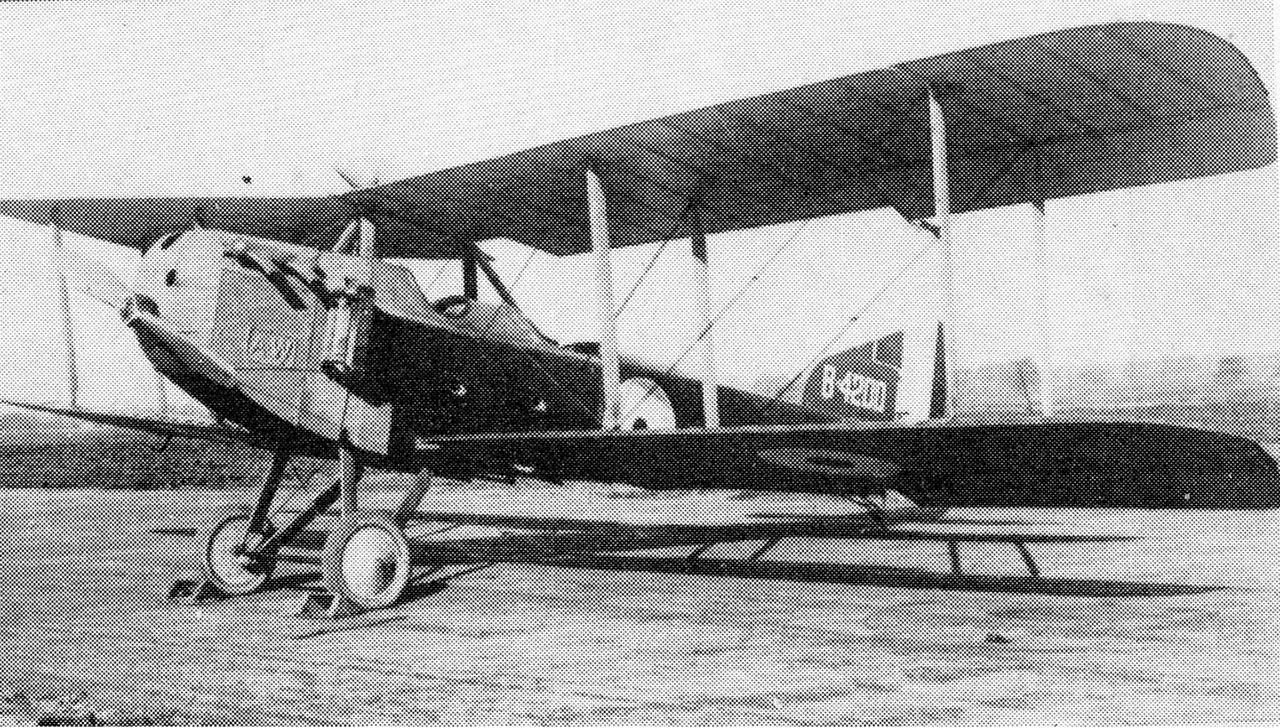

The first occupancy was a flight from 50 Squadron, based at Bekesbourne (Canterbury), which arrived on 3rd October 1916. The other Flights were based at Harrietsham (Frinsted) and Bekesbourne. There were no permanent structures: any accommodation was probably tented, and if a hangar existed, it would likely have been a temporary wood-and-canvas Bessoneau structure similar to the included image.

It may be that part of Rumney Farmhouse was requisitioned to provide water and electricity and used as an office or for officer accommodation, but administration and overall command were run from Bekesbourne. Quite likely, aircraft would be flown to Bekesbourne for maintenance during the day and return in time to be refuelled for a night patrol.

To put this into context, it is worth remembering that flying was still very much in its infancy: the first ever powered flight had taken place just 13 years earlier, and the first ever cross-Channel flight (over which there were now daily flights) a mere 7 years previously.

Flying at night was particularly perilous and could only be done in clear moonlit conditions with the aid of paraffin flares lining the grass “runway”. Flying in the darkness in a freezing open cockpit, finding your target and shooting it down whilst it was trying to shoot you down was, to say the least, extraordinarily challenging. It is therefore unsurprising that one of the pioneers, Lieutenant Leefe-Robinson, was awarded the Victoria Cross for shooting down the first Zeppelin in 1916 whilst flying from the Home Defence Landing Ground at Suttons Farm (Hornchurch) just across the Thames Estuary.

50 Squadron operated a mixture of BE2 and Armstrong Whitworth (AW) F.K.8’s, which were largely obsolescent training aircraft. However, in response to a raid on 7 July 1917 in which bombs from 22 Gotha’s inflicted 57 deaths and 193 injuries in London, a 50 Squadron AW F.K.8 shot down a Gotha bomber off the North Foreland of Kent. (The location of the interception would suggest the aircraft was not from South Ash).

In February 1918, 50 Squadron departed South Ash (Wrotham) to re-equip with the Sopwith Camel. Its then Commanding Officer was Major Arthur Harris, later to receive notoriety as Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Harris, Commander in Chief of RAF Bomber Command in WW2 and whose statue outside the Central Church of the RAF St Clement Danes in the Strand was sculpted by Faith Winter, who also sculpted Stansted’s War Memorial figure. They were replaced by a Flight from 141 Squadron based at nearby Biggin Hill flying the Bristol F2b Fighter.

The last and largest aeroplane raid of the war took place on the night of 19 May 1918, when 38 Gothas and 3 Giants took off against London. Six Gothas were shot down by night-fighters and anti-aircraft fire; a seventh aircraft was forced to land after being intercepted by a Bristol Fighter of 141 Squadron from Biggin Hill. Lieutenant Edward Turner and Lieutenant Henry Barwise fought a long engagement with the Gotha. This was the first victory of the war for Biggin Hill, for which Turner and Barwise were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. There is every possibility they flew from South Ash at some point.

The hastily cobbled-together Air Defence strategy between 1916-18, and the lessons learned, were directly responsible for bringing about the merger of the RFC and RNAS to create the RAF as a single unified fighting force in 1918.

Following the Armistice, there was no future for most of these small Landing Grounds. A few became permanent RAF establishments (e.g., Suttons Farm/Hornchurch), and a few still survive (e.g., Frinsted) as private airstrips. Stow Maries, just the other side of the Dartford Crossing, is unique in having preserved all its WW1 infrastructure and continues to operate period historic aircraft. South Ash (Wrotham) closed in 1919 and was returned to agriculture.

No independent corroboration exists as to whether Craven Hohler subsequently based a light aircraft there, but he was an officer in the Auxiliary Air Force from 1932. As a member of the exclusive 601 “Millionaires Squadron”, he would have been no exception to the generally stated belief that membership criteria required that you owned your own aircraft, but regardless, it isn’t beyond the realms of possibility to imagine he may have occasionally found an excuse to “drop in” whilst flying locally.

In 1940, the Landing Ground was once again the focus of a fleeting but tragic military connection when the shattered body of Unteroffizier Kurt Hausburg was found embedded in one of the fields in front of Rumney Farm. He was the observer of a Dornier 17 and, along with another crewman, had bailed out after it had been damaged by RAF Fighters. Unfortunately, his parachute failed to open. He was buried in St Mary’s Church, and rested there until 1962, when his remains were exhumed and reinterred at the German War Cemetery at Cannock Chase, Staffordshire. The full story of this incident and the tragic aftermath when his aircraft crash landed in Barnehurst can be found here and also in Sheila Parker’s recollections of growing up in WW2.

German air raids on Britain cost between 1400-1500 lives and 3,400 injuries during WW1, and whilst this pales into insignificance when compared to the devastation wrought by air raids in WW,2 it is extraordinary to think that sleepy Stansted played a pioneering role in the Air Defence of Great Britain.

Author: Mike Goddings

Contributors: Dick Hogbin

Editor: Tony Piper

Last Updated: 29 January 2026