Luminaries: Alfred Wintle

Colonel A D Wintle featured on the BBC Radio 4 programme Desert Island Discs, originally broadcast in 1962, and was interviewed by Roy Plomley.

The programme was archived without his selected music tracks which are not part of this recording.

Colonel Alfred Daniel Wintle, MC, better known as A.D. Wintle (30 September 1897 – 11 May 1966), was a British military officer in the 1st The Royal Dragoons who served in the First and Second World Wars. He was the first non-lawyer to achieve a unanimous verdict in his favour in the House of Lords and is considered one of London’s greatest eccentrics. He was a long-term resident of Stansted, Kent, living at Coldharbour, Wrotham Hill Road, from 1930 until he died in 1966.

Note: The Royal Dragoons were a heavy cavalry regiment of the British Army. The regiment was formed in 1661 as the Tangier Horse. It served for three centuries and was in action during the First and Second World Wars. It was amalgamated with the Royal Horse Guards to form The Blues and Royals in 1969.

The son of John Edward Wintle, a diplomat, by his wife Emma Teresa (née King), Alfred Daniel Wintle was born in Mariupol, East Ukraine, in 1901. The family moved to Dunkirk, and he was subsequently educated in France and Germany, becoming fluent in both French and German. Alfred Wintle’s grandfather had married twice, having four children with his first wife and three with his second. One of his four children with his first wife had three children (‘Kitty’, ‘Millie’ and Arthur) and one of his three children with his second wife (Alfred’s father) had seven children, including Alfred. The relationship (half-cousin) between Alfred and Kitty was to be the cause of perhaps his greatest achievement, unanimously winning a case in the House of Lords as a non-lawyer.

At the outbreak of war, 16-year-old Alfred Wintle was in Dunkirk and claimed to have “irregularly attached” himself to Commander Samson’s armoured-car unit, witnessing Uhlans being shot in Belgium.

Note: In 1914, Uhlans were German light cavalry armed with lances, sabres and pistols. After seeing mounted action in the early weeks of WW1, they were dismounted to serve as ‘cavalry rifles’ in the trenches. All 26 German Uhlan regiments were disbanded in 1918-19.

Wintle wished to see military action, and in summer 1915, his father agreed to his son’s early entry into the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He was commissioned in less than four months (Service no 14308) and, less than a week later, he was at the Front. On his first night, a shell burst near him, splashing over him the entrails of his sergeant (to whom he had just been introduced). Wintle later admitted to being petrified. As the bombardment continued, he dealt with his fear by standing at attention and saluting. As he later wrote, “Within thirty seconds I was able to become an Englishman of action again and to carry out calmly the duties I had been trained to perform”.

The incident was typical of both a series of amazing escapes and his pride in being an Englishman (as opposed to being born “a chimpanzee or a flea, or a Frenchman or a German” – as he later said). He saw action at Ypres, the Somme, La Bassée and Festubert. His luck ran out during the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917 as he helped to manhandle an 18-pounder field gun across a “crater-swamp”. The gun carriage wheel hit an unexploded shell, and he woke up in a field hospital without his left eye, left kneecap and several fingers. At age 19, Wintle’s right eye was so damaged that he had to wear a monocle with 5x magnification for the rest of his life.

He was sent back to England to convalesce by the “infernal quacks”, and it appeared that his war was over…but Wintle had other plans. He was soon organising his escape from the Southern General Hospital back to the front, attending a nurses-only dance in their billets (disguised as a nurse) before finally making his escape. He recorded that his monocle was a dead giveaway, and a particularly unpleasant matron was unimpressed with his antics.

Wintle was entrained for France with a warrant signed by a friend of his father’s. He had a “moderately successful year of action” with the 119th Battery, 22nd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (RFA). His Military Cross was gazetted in the London Gazette of 2 April 1919, and he received his medal the same day. He said in his autobiography: “I received through HM registered post, a small box. It contained a Military Cross; I was quite astonished.”

The citation, which accompanied it, read: “For marked gallantry and initiative on 4th Nov. 1918 near Jolimentz. He advanced with the infantry to gather information and personally accounted for 35 prisoners. On 9th November, he took forward his section well in front of the infantry and throughout the day he showed initiative of a very high order and did excellent work.”

Wintle said, “And, d’you know, for the life of me, I could not remember with any distinctness the two incidents referred to. They had merely been part of an exciting, ever-changing pattern of a soldier’s life in the last few weeks of the War. Dammit, that was when we were really moving forward at last”.

The following are the only two entries in Wintle’s diary on two days in June 1919:

- “Great War peace signed at last.” (19 June 1919)

- “I declare a private war on Germany.” (20 June 1919)

According to his autobiography, he “knew that the war with Germany was not over. They were merely lying low … and the curtain would go up on Act Two” when the Germans were ready. He was outspoken about politicians and bureaucrats who “had had a very easy war and were intent on having an even easier peace”, and was frustrated at the lack of action to prevent the rise of Germany’s military might.

In 1920, just before his 23rd birthday, Wintle was posted to Ireland as an officer in charge of Intelligence in the Limerick Brigade Area. This was during ‘The Troubles’ and “murders, lootings, ambushes, searches and patrols kept us on the alert”. The same year, his Cavalry posting to the 18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary’s Own) took him to Secunderabad in India, where he spent just over two years.

Note: Secunderabad is now part of Hyderabad in central India.

In 1923, he was posted to Cologne as Assistant Garrison Adjutant, attached to the GHQ Staff of the Rhine Army. It was here that he was strengthened in his belief that the ‘English did not take a strong enough line with the Germans in the ‘twenties’ and ‘thirties’ …and the result of our collective weakness was Hitler’s War.”

Late in 1923, Wintle got “his heart’s desire” when he was posted to First, The Royal Dragoons – “The Royals” for short – Britain’s First Cavalry Regiment of the Line and “the finest in the World” and was stationed at Aldershot. He had been posted to ‘C’ Sabre Squadron and took over the 3rd Troop of about thirty troopers. Again, his lasting impression was that no one in authority was taking training and preparation for another war with Germany at all seriously.

By 1927, Wintle was a Captain and was briefly stationed in Cairo before being sent back to London to join the German Section of Military Intelligence at the War Office. He later said: “The more I look back on that period from 1927 to 1929, and the events that followed it, the more I realise what a complete waste of time it was.” “Ten years after World War One, it should have been obvious, even to a one-eyed ignoramus of a Cavalry Captain, that a resumption of war with Germany in the late ‘thirties was inevitable.”

Wintle’s unhappiness at the War Office was reciprocated, and late in 1929, he was told to rejoin his Regiment in India. Once there, he got septicaemia and returned to England to get well. During a long period of convalescence in 1930, he decided to buy a house. In his autobiography, Wintle recalls:

“Perhaps subconsciously, I had formed ideas about the home that I wished to have. I knew that it had to be English and reasonably remote; a place of beauty and tranquillity; one conducive to thought where I could write without undue interruption. I found Coldharbour. I bought Coldharbour, my still-dearly beloved home in the Weald of Kent, and began to rebuild it. I knew all about it at the very first glance. I knew immediately that I should spend my declining years there and would never want to wander again. Coldharbour, Wrotham, Kent. What could be more English? It is also a remote, beautiful and peaceful – four and a half miles from the nearest village and nearly 2 miles from my nearest neighbours and staunch friends, Dame Sybil Thorndike and Lewis Casson.”

Note: The listing details for Coldharbour Farmhouse off Wrotham Hill Road: 16th century, restored. Redbrick ground floor, rendered on the first floor, timber-frame exposed to the north. Plain tiled roof with ridge stack off-centre to the left and south, and a stack with a projecting breast. 2 stories. Irregular fenestration of three windows on the 1st floor, 2 windows on the ground floor, and a casement. Gabled weather porch with a door at the entrance right.

“Coldharbour is not on the way to anywhere. It stands in a cul-de-sac at the end of the deep-rutted lane, arched and bowered with ancient English trees. Its haunting charm has withstood the ravages of time. Its open fireplaces are large enough to roast an English ox in each. Though overgrown, its grounds were fertile and offered a challenge.

Coldharbour has many rooms and many doors of solid English oak, each with solid oaken latches. All the windows are mullioned, their diamond-shaped panes winking welcomes. Stairs are sturdy, creaky and crooked, again of the finest oak in the world. Some of the floors are paved with stone slabs; others are of Elizabethan tiles.

I walked around Coldharbour, saw the rich soil in the adjacent fertile fields and apart from its natural thrush and blackbird symphony, I heard its magnificent silences. It was the first and only home of my own.”

Note: In 1930, Alfred Wintle bought and moved to the Grade II listed Coldharbour Farmhouse and still lived there when he died on 11th May 1966. It is ironic, given his animosity towards the German race, that he died just 10 weeks before the England football team beat West Germany 4-2 in the final of the World Cup.

“Much work to be done before my study could be brought to writing order, a much more work before I could plant English flower seeds in Crystal Palace – as I immediately christened my greenhouse– and before I could erect my flagpole which would fly the flag of The Royals.”

“When I first found Coldharbour, I noticed –on a little triangular patch of grass at the meeting of three side roads near a pub called the Horse and Groom–a signpost pointing in my direction which read, ‘To Labour in Vain – 1 mile’. This was such an appropriate, if sinister portent that I have always regarded it with a certain amount of sympathy.

It was, in fact, the name given to a small group of houses which had been fashioned from a rambling tavern long since disappeared, and for which the sign had been a white woman scrubbing a little nigger boy. Apparently, this was not an unusual inn sign in England at that time. Many of my friends who came to see me noticed it and, in view of the Herculean task I had undertaken to restore the place, insisted it was ominous. I did, however, manage to get Coldharbour straightened out in time.”

I kept several ponies at Coldharbour and took part in the local activities in this respect. People, like Descartes, who say that animals are incapable of reason might well consider the following incident involving my old dog, Jumbo. When I first found Coldharbour, it was almost in ruins. There was an enormous amount of work to be done in the place. As soon as I could, I straightened up one of the rooms and used to go there and camp out while I worked. Jumbo would sleep there some nights.

I had a helper, Cox, who used to come every day to assist me, arriving at 8 o’clock in the morning. He lived in an old Army hut in a field about half a mile from Coldharbour. He would cut across from his hut, climb a stile and join my lane about 400 yards away.

Jumbo used to hear Cox the moment he got into the lane. I would usually be asleep and always in bed at this hour. And as soon as Jumbo heard Cox, he would wake me up by growling and keep growling until I reassured him by showing signs of life and telling him that all was well and that I, too, had heard the footsteps.

At two o’clock in the afternoon, when Cox returned from his midday meal, Jumbo would again hear him 400 yards away. This time, he would merely stand the open door wagging his tail expectantly. Never in the afternoon did he bark or growl, thus showing me that, as I was up and awake, it was not necessary to warn me.”

Cox continued to help with the improvement work at Coldharbour and, indeed, stayed for many years. One of his tasks was to build a woodshed, “To accommodate the logs for my fireplace, allowing sufficient space for me to saw logs undercover, to the precise dimensions required. But first, these have to be sawn from fallen tree trunks in the various copses and hedgerows in the environs of Coldharbour. This is quite a task in itself and one which I usually perform in late summer or early autumn before carrying the resulting great logs upon my shoulder to the final sawing point. I have no power-driven saw, but I am the proud possessor of several handsaws of various shapes and sizes, each able to cut through sturdy oak, elm and ash – all good burners and heat producers”.

“Apart from the welcome exercise, I gain many benefits from the sawing of logs. There is the pleasant smell of the wood itself; there is a fine, soft carpet of sawdust to rest my feet, and I tend to hum or whistle whatever favourite hymn or march tune comes to mind and suits the rhythm of my sawing.”

Photo: P1026-08 Logs at Coldharbour

Wintle moving logs at Coldharbour Farmhouse in the 1950s

From 1931 to 1935, Wintle served as an instructor at the French Staff College (École de Guerre) at Saint-Cyr, Paris. He was particularly disparaging of the French, including the following remarks:

“Even at the height of French greatness, under Louis XIV, they were never as mature as we were and are. And they have only been a little nation since 1918…a mean, little nation playing at being a first-class power. What impudence. And what fools we have been to be taken in by their posturing.”

“The trouble with the French is that the boys are never beaten at school and consequently, they have never really become housetrained. The result is that one sees grown and elderly men exhibiting all the tricks of the untrained and immature infant. They pick their noses, they play with their knives and forks, they draw with the tip of their teaspoon on the tablecloth, they make designs with the spoon in the salt cellar and worst of all, they practice indiscriminate evacuations of their bowels in the manner of public functions. These are all the tricks that one finds in the nursery in an untrained child, but which training at home with an occasional swift clout at school later on quickly eliminates.

I have yet to meet one Frenchman in whom the cloven hoof or hairy heel has not sooner or later become apparent. Not even the lowest caste Hindus abandon themselves to such excess of unrestraint as the French. To interact with French people, even in France, is a constant strain on one’s self-respect. It is also a matter of anxiety and uncertainty, and should the party be accompanied by children, this strain is immeasurably increased.

Wintle returned to London in 1935 and observed that “it was peacetime soldiering at its cushiest, this even though the second half of the German war was only four years away. Life revolved around polo, children, pony clubs and other such irrelevancies.” By 1938, Wintle was with the Air Ministry whilst officially being on the strength of Military Intelligence at the War Office, and he shuttled between the two places. He was unimpressed by England’s preparations for War:

“Our slowness during the year we gained at Munich was appalling. The net result was that, although we were less unprepared, we were in the worst position relative to Germany. If our leaders had been deliberate traitors, they could not have played Germany’s game better than they did. If anything is worse than treachery in such matters, it is ignorance and stupidity. That Chamberlain could not face the realities is as apparent then as now. But that his advisors bungled the situation is criminal.

Alas, the system in vogue at that time encouraged inaction and dithering. It was typical of the way things were that we did not consider setting up a board to plan the mass production of tanks until May 1940. “It was the pitting of amateur players against professional gangsters. It was a period when worthy but uninformed, unprepared and untrained laymen were improvising and muddling in the face of the organised ruthlessness of professional maniacs.”

When World War II began in September 1939, Wintle tried everything to persuade his superiors to allow him to go to France. When they refused, he planned to resign his commission and form his own army “to take the war to the Hun”.

After the French surrender, Wintle demanded an aircraft (with which he intended to rally the French Air Force to fly their planes to Britain and continue fighting Germany from British airbases); when refused, he threatened an RAF officer (Air Commodore A.R. Boyle) with a gun. As Wintle says in his autobiography:

“I saw all right. I saw red and cursed him fluently. ‘While you sit there,’ I concluded, ‘blood is flowing in France, not ink. And I am deadly serious. I then drew my revolver and waved the muzzle under his nose like a warning finger. ‘You and your kind ought to be shot,’ I snorted. And I named a few top people who deserved it as much as he did. I then broke my revolver, spilt out the bullets to show I had not been bluffing and left him shaking with fright. I returned to my unit in the North that night. Next morning, I was arrested.”

It was alleged that he had threatened to shoot himself and Boyle, and for this, he was imprisoned in the Tower of London. On the way to his prison, a young soldier escorted the lieutenant colonel via a train. The soldier is reported to have lost the travel warrant; disgusted, Wintle declared the man incompetent, told him to wait where he was, and went to get a new warrant. Since there was no other officer of higher rank at the warrant office, he signed the paper himself. As he recalled in his autobiography:

“This must surely make me the first, and only, prisoner who has ever signed his own travel warrant to the Tower of London”.

Of his time in the Tower, he wrote: “My life in the Tower had begun. How different it was from what I had expected. Officers at first cut me dead, thinking that I was some kind of traitor; but when news of my doings leaked out, they could not do enough for me. My cell became the most popular meeting place in the garrison, and I was as well cared for as if I had been at the Ritz.”

“I would have a stroll in the (dry) moat after breakfast for exercise. Then, sharp at eleven each morning, Guardsman McKie, detailed as my servant, would arrive from the officers’ mess with a large whisky and ginger ale. He would find me already spick and span, for though I have great regard for the Guards, they have not the gift to look after a cavalry officer’s equipment.

The morning would pass pleasantly. By noon, visitors would begin to arrive. One or two always stayed for lunch. They always brought something with them. I remember one particularly succulent duck in aspic, which gave me indigestion, and a fine box of cigars brought by my family doctor.

Tea time was elastic and informal. Visitors dropped in at intervals, usually bringing along bottles that were uncorked on the spot. I don’t recall that any of them contained tea.

Dinner, on the other hand, was strictly formal. I dined sharply at eight and entertained only such guests as had been invited beforehand. After a few days of settling in, I was surprised to find that – as a way of life – being a prisoner in the Tower of London had its points.” When his case was heard in 1940, Wintle was read the three charges against him.

- The first was that he had feigned defective eyesight (and infirmity, to avoid active duty). This charge was dismissed after Wintle’s defence provided evidence that he had volunteered for active service several times and had, in fact, pretended not to be blind in an eye that was blind.

- The second charge was assaulting Air Commodore Boyle. This was reduced to a charge of ordinary civil assault during the proceedings, and on this lesser charge, Wintle was found guilty and sentenced to a severe reprimand.

- The third charge was conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline in that he had produced a pistol in the presence of Air Commodore Boyle and had threatened to shoot himself and the said to the Air Commodore words to the effect that certain of His Majesty’s Ministers, all officers of the Royal Air Force above the rank of Group Captain and most senior Army officers ought to be shot. Far from denying this, Wintle admitted the act and produced a list of people whom he felt should likewise be shot as a patriotic gesture. The list must have been a topical one; after he had read out the sixth name upon it (Hore-Belisha, then Secretary of State for War), that charge was also dropped.

On 4th October 1940, Wintle was sent abroad to rejoin his old regiment (1st The Royal Dragoons) and went into action gathering intelligence and coordinating raids on the Vichy French in Syria. After the Allied victory in Syria, Wintle was asked to go to Vichy France in disguise to determine the condition of British prisoners-of-war held there. While waiting to make contact with sympathetic elements of the Vichy French government in October 1941, Wintle was betrayed, arrested as a spy and imprisoned in Fort Ste Catherine in Toulon.

During his captivity, he informed his guards that it was his duty as an English officer to escape; he succeeded once by quickly unhinging his cell door, hiding in a sentry box, and slipping out quietly, but was betrayed and recaptured after a week. Wintle’s guard was doubled from this point on.

He responded by going on a 13-day hunger strike in protest against the “slovenly appearance of the guards who are not fit to guard an English officer!” He also informed anyone who would listen (including Maurice Molia, the camp commandant) exactly how he felt about their cowardice and treachery to their country. He informed them that he still intended to escape and that anyone who called himself a Frenchman would come with him.

Shortly after, he sawed through the iron bars of his cell, hid in a garbage cart, and slipped over the wall of the castle, making his way back to Britain via Spain.

Molia later claimed on Wintle’s This Is Your Life programme in 1959 that shortly after the escape, “because of Wintle’s dauntless determination to maintain English standards and his constant challenge to our authority,” the entire garrison of 280 men had gone over to the Resistance.

Wintle spent the rest of the War most actively, fighting in the Middle East, Burma and Italy, and – for the second time – in occupied France.

From this time up until the end of his life, he was a regular at The Horse and Groom, The Vigo and The Bull public houses. As he said in his autobiography, “Pubs and clubs – those gloriously English institutions – are two of my passions. I think of Sam Gould, the publican at the Horse and Groom at Wrotham. He was a Guardsman of the Grenadiers. If ever I had had any doubts about the Guards, he would have dispelled them.”

In 1944, Alfred married Dora Burgess. He said of their relationship:

“My darling Dora – the best friend I have ever had, male or female. I had known her since 1915, when my father had taken me to visit her family on our way back from The Shop after my first interview. As she lived at Bromley, I had been able to visit her there from Woolwich fairly frequently and over all the years until our marriage in 1944, at St. Margaret’s, Westminster, we had corresponded constantly. I should add that our maternal grandmothers were sisters, which backs up the view I have always held that you should never marry a stranger.“

Note: Dora Elizabeth Burgess (born 1893; died 1974). ‘The Shop’ is a nickname for The Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, SE London.

After the war, aged 48, he stood as a Liberal Party candidate for the 1945 General Election at Norwood. The seat had little Liberal voting tradition, and he finished third with about 11% of the vote. He later said, “When I retired from the Army in 1945 by becoming a Liberal Parliamentary candidate for West Norwood, I knew what I was doing. Further promotion was being denied me because of my unconventional actions in the war and my disrespect for many of my so-called betters. When I retired, I did not expect to win in Norwood. It was a quick and cheap way of getting out of the Service.”

Of Coldharbour, he said: “In settling at Wrotham, I certainly was not escaping from life. I was moving into a new and wonderful one. Around me were some of the most fascinating of God’s creatures, with much to teach me that I had neglected to learn while travelling the world.

First, there were my wife’s Dogs. Sally, her golden copper bitch, had a coat of burnished gold. She would come at my whisper. She was devoted, loyal and fully obedient without being unduly submissive.

Then there was Dinah, my cat. She was pure Persian and had a pedigree as long as the Edgware Road. Unlike inferior cats, and possibly all other cats, she never curled contentedly for wasted hours before my log fire. Dinah had more useful things to do in the great outside, and there was a great deal of the great outside in Coldharbour. There were ploughed fields, wooded lanes and undulating meadowland, all abounding with potential prey for Dinah.

Coldharbour would have been a less pleasant place without Hugo, of whom I was particularly fond. He always reminded me of the Lord Chancellor of England and wore a feathered hood upon his clover head. Like the Lord Chancellor – who was to come out on my side, bless him, in the House of Lords – Hugo was a wise old bird. He was, in fact, an owl and lived in Coldharbour’s roof.

We were then much consoled by Micky’s attendance in the evening. Each evening, without a visiting card or a by your leave, he would drop in on us for a spot of warmth and conviviality and would squat upon his diminutive haunches before my log fire. Micky always came alone, and for that we were glad. He was a field mouse– no, a mouse and a half. Micky more than made up for all the other mice who might have wished to be present. In the depths of winter, braving ice, snow, sleet and hail, he would attend on time, and never a squeak of complaint about all that he had endured. Mind you, I should have been astonished had a squeak of any kind come forth from Micky. From him, I should expect nothing less than a roar.

Micky was an English Field Mouse, a Mousey Field Marshall and superior by far to his Scottish cousins who – so rightly – were once described by some ploughing, poetical person or other as: ‘Wee, sleekit, cowerin’, timorous beasties’. I liked Micky. He sometimes nodded off to sleep – then so did I.”

“I had many good friends in the Wrotham area and would ride over to see them, as a relief from the rebuilding of Coldharbour. Among them were the Gordon-Browns, who lived in some style at Wrotham Hill Park. One day, Gordon-Brown, in going around his estate, concluded that the apples in his orchard were not producing all they might. I should mention here that Gordon-Brown always had at the back of his mind the hope that it might be able to offer a drink to whoever might happen to come along. In the same way that the suspicious countryman, upon seeing the stranger, thinks that the best thing to do would be to heave half a brick in his direction, I should imagine Mr Gordon Brown’s mental processes worked something like this: ‘Hullo, a stranger. Let’s offer him a drink and then a meal with perhaps a second drink between the two, not to mention some wine with a meal and a glass or two of port at the end.’

So that, when Mr G-B. saw all those apples, probably going to waste, he immediately thought of cider. He set to work rounding up the apples and sending them for me. Together, we mobilised every basin, pot, jug, tub and barrel we could lay hands on in the cellar. Old trouser presses were pressed into the service of the cider. And, eventually, innumerable apples were pulped, pressed, squeezed, and their juice dripped from basin to pot, from pot to pan and jug and tub, until finally we filled a couple of barrels with the health-giving liquid. Then we adjourned, and the barrels were left to themselves in the cellar. We had done all we could, and it was now up to them.

Nevertheless, Mr Gordon-Brown went on turning over the subject of cider in his mind and, one day, happened on a book that went into the subject more fully than either of us had ever done. In particular, this book pointed out that, while nature was wonderful, art or artifice might help. It is recommended to add a small amount of alcohol to the maturing cider to assist fermentation. Gin, in particular, the book said, was a desirable additive. This seemed to G-B such good common sense that he immediately took two bottles of gin and poured one into each barrel.

The next day, he wondered if he had not, perhaps, been a little niggardly in the matter of gin-adding. So, he took down two more bottles of Gordon’s and added them to the barrels. In the meantime, he had left the book lying around the house, and Mrs Gordon-Brown, happening to glance at it – and being equally interested in the mysterious process in the cellar, came upon the article. As a kind surprise to her husband, she also added a bottle of their namesake to each barrel. Nor were the rest of the family inactive. They too read the book and did their best to make a father’s recipe a success.

In fact, as far as I can make out, whenever anybody in that household had nothing much to do, which was quite often, he or she would add gin to the cider. And meanwhile, the cider went on in its quiet way, doing its stuff. No doubt each fresh addition of gin gave it fresh encouragement, and one can imagine it going from strength to strength, doing its daily dozen quietly to itself and working up its muscles against the day that should be lapped. Then, one day, when I was there, Mr Gordon-Brown decided to tap the cider. He sent for his butler and told him to go down to the cellar and bring up requisite quantities of cider, for we were seven that day.

Dale, the butler, disappeared, and presently the strong smell of apples spread throughout the house. This was followed soon after by the appearance of Dale bearing, on a silver tray, seven silver pint pots of cider. The smell of apples and juniper became immediately paramount. We drank our delicious cider.

Personally, I can remember nothing more. Nor, on comparing notes later, did I find much memorising among the others.

This was the most potent liquid any of us had ever drunk. It was only subsequently that the reasons for its potency became clear. But there is no doubt that, as a method of improving cider, it cannot be bettered.”

“At this time, the Gordon-Browns had lived in their lodge, a terrible old woman called Mrs Ewers. From time to time, they gave her old clothes. She would put these on top of the clothes she was wearing at the time of the donation, and presumably, the underclothes gradually dropped off because her overall bulk never increased.

“One day, I saw her in the road carrying a huge bundle up the hill. I stopped the car and offered her a lift, this even though although we knew each other by sight, we had never been formally introduced. She replied, to quote her absolutely: ‘Oh, dear me, no!’ and walked on. Mr Gordon-Brown said he imagined she thought I was going to rape her. He was probably right.”

Anyway, her stories of her lamented husband, the late George Ewers, as related to me by the Gordon-Browns, were startling. George must have been a singularly useless member of the community and also rather a blot on the body politic.

Once upon a time, he was employed at the Vigo Inn. There he was so idle and feckless that he was given the sack. And these publicans, as is well known, are a bit careless in their talk. So, George Ewers was sacked to the accompaniment of well-rounded phrases that described his character, appearance, and eventual destination. One presumes that the language used was that found only in the less well-known parts of the Bible.

Whereupon, George Ewers went down on his knees and, lifting his eyes up to heaven, muttered: ‘May God forgive this wicked man and make him pure in heart’. Apparently, the landlord of the Vigo was never the same man from that day on, and died of thought-dulling drink, poor chap.”

Alfred Wintle also became very keen on gardening and spent more and more time in his lean-to greenhouse that he had christened – soon after he had bought Coldharbour in 1930 – Crystal Palace. In his autobiography, he says: “In that pleasant place, I enjoy many hours, and although I may never become as green-fingered as the experts– having four fingers fewer than most –the results of my labours are highly satisfactory and sometimes bring fulfilment– which is all you can ask of this life, even in England.

My Russell Lupins give me great joy, for they stand in serried ranks and colourful abandon, erect and splendid as Guardsmen. The Lupin is a delicate fellow, to begin with. He has to be nurtured and coddled considerably before he can stand stiffly at attention on sentry-go in my garden’s borders. But he and his brother officers are well worth the trouble.

It has always been a customer of mine to give cuttings, roots and seeds of my garden flowers to friends and visitors, for I like to think that when a flower which begins its life in Crystal Palace comes to bloom in places elsewhere, its presence there may inspire in the persons to whom it has been given a kindly thought for Coldharbour and its occupants.

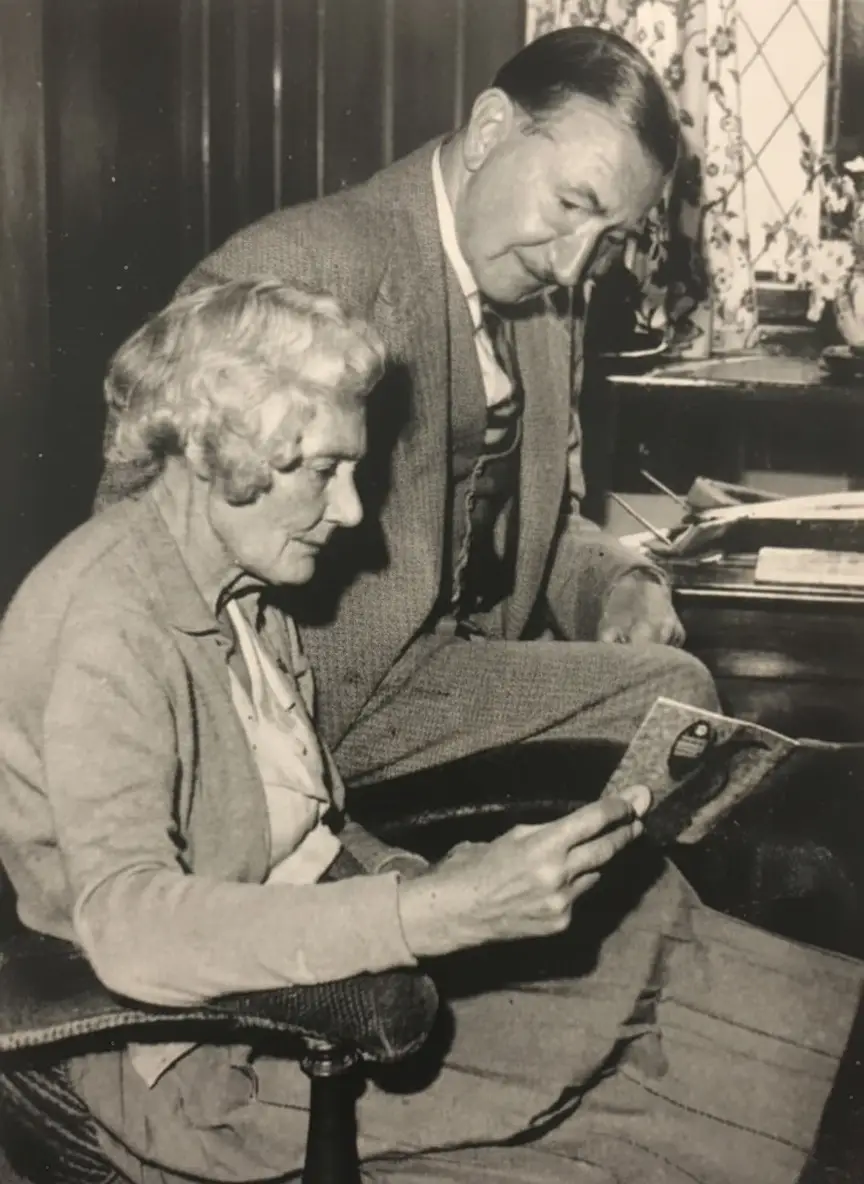

My wife and I spend much time in potting and planting with this in view, and some of our gifts have been much praised, particularly the cacti of which I have kept wide varieties. We collect a sprinkling of the new life each year and plant them carefully in soil or peat in various seashells and pots. We give these oftentimes to friends, and it is most pleasing to learn that our cacti give pleasure to others in many parts of England.

Into this sort of scene of domestic post-war bliss, there obtruded my long battle with the law, which was quite a chapter in my life.”

Following the war, a dispute began that would take Wintle to the Law Lords. He formed the view that a Brighton solicitor called Frederick Harry Nye had conned Kitty Wells, his elderly female half-cousin, into leaving him £44,000 in her will. In Wintle’s view, Kitty had often said that she had left her money to Wintle’s unmarried sister Marjorie and that the highly complex wording of the will had hoodwinked her.

Note: Kitty lived with her sister (Millie) in Steatham, London, then moved to Orpington and subsequently to East Grinstead. Her final home was with Marjorie Wintle at Seacroft in Hove. Whilst living at Hove, her solicitor was Frederick Harry Nye.

Wintle’s methods did not initially follow the Rules of the Supreme Court: He forced Nye to remove his trousers and took photographs to shame him into returning the cash.

As a result, in 1955, Wintle was imprisoned for six months for assault. He then took the more orthodox route of issuing proceedings to contest the will. As he said in his autobiography: “I immediately leapt into the saddle, calling up numerous costly outriders in the shape of solicitors, barristers and the like. I held rehearsals at Coldharbour with my friends playing the parts of the people I would encounter in court.

It cost me all my possessions to prepare my case –my furniture, pictures, silver: everything I had collected over the years. Even the house had to be mortgaged. To help me out, my wife also sold many of her prized things, which can never be replaced. She is a treasure beyond price. For the ten years of my legal war, I was never able to take her away for a single day’s holiday.

Her encouragement, example and unfailing support carried me through many dark days. Her humour – God’s greatest endowment – always helped me. Through all the fight, she never spoke a word of reproach or even caution.

All of which shows how right, as I’ve said before, I am in believing you should never marry a stranger. Alas, my outriders proved to be less reliable companions. In the manner rather of dismounted Portuguese refugees, they all spilt the first ditch – the Probate Division of the High Court.”

At trial, the jury rejected Wintle’s accusations in its entirety, and costs were awarded against him. Wintle, by now out of funds and decided to act in person in his Appeal to the Court of Appeal, assisted by ex-Dragoon Mays. As Wintle said, “You know where you stand with cavalrymen.”

“One wet and miserable day shortly before the appeal, I invited Dame Sybil Thorndike, Sir Lewis Casson and Mays to Coldharbour for lunch. Next to my wife, they were my stoutest supporters. The rain was coming down in torrents, and it occurred to me that they might have decided not to come after all. But the bell rang, I walked to the front door, and there was Dame Sybil. I’m not sure whether she was seventy-seven or eighty-three at the time, but there she was, bless her, with a kind of transparent tarpaulin over her head, a sturdy Macintosh covering most of her and Wellington boots to boot. In her arms, she clutched two useful-looking bottles. She was singing at the top of her voice….’ I’m singing in the rain, I’m singing in the rain…. What a glorious feeling, I’m happy again…’ She had just walked through two miles of mud.

I welcomed her, enquired after her health – a superfluous question, as she was always a picture of health and vigour – and then asked where Lewis was. “He won’t be long,” she replied. “He was repairing the roof when I left.” You see, one of the tiles has gone awry, and this dreadful rain might get through. He won’t be long, my dear.’

I’m not sure whether Sir Lewis was seventy-seven or eighty-two at the time, but between them, this magnificent pair has a joint age of around 160. Sir Lewis came along shortly, and he thought it nothing out of the ordinary to have been working at the top of a 42-rung ladder in the pouring rain. That’s the way to live your life – at the beginning, in the middle and at the end.”

Note: Dame Sybil and Sir Lewis at the time lived in Cedar Cottage, a c17 house at the junction of Wrotham Hill Road and the lane leading to Coldharbour. Further information on Sybil Thorndike is available in the ‘People’ section, under the ‘Luminaries’ category..

Wintle lost his case by a 2-1 majority. “One of the three bewigged and black-robed Lord Justices, in an opinion of luminous lucidity, agreed with me. Both the other two insisted that Kitty’s will should stand, so I was unhorsed again. ‘Let’s go and have a drink’, said Mays, dejectedly. ‘No,’ I replied. ‘We’ll go down to the Embankment and spit in the Thames for luck. ’ Which we did.”

In 1958, he then appealed to the House of Lords and appeared in person before five Law Lords.

“As a layman in this professional holy-of-holies, I felt a bit like a Dragoon charging a squadron of tanks. But I screwed my monocle more firmly into my eye socket, took a prodigious pinch of snuff and drew my brief from my briefcase.”

At some stage, during a hearing of six days, Viscount Simonds interrupted Wintle to suggest that it was quite clear that no one in any of the Courts had understood the will and its complications.

“I think I won my case at this moment when I had the presence of mind to reply quickly; ‘Would it be presumptuous, My Lord, to suggest the somewhat simple Miss Wells may well not have understood it either?”

Research note: Kitty Wells was described by Wintle as ‘good, kind but simple-minded’. She spent many hours copying longhand pages from dictionaries and telephone books. She was inordinately worried her whole adult life by her sister’s conversion to Catholicism and her brother’s divorce and remarriage. Arthur Wells (Kitty’s brother) was a barrister, but he was estranged from the rest of the family after divorcing and remarrying.

Wintle won his appeal to the House of Lords unanimously. This was on the ground that the trial judge had not properly conveyed to the jury the burden that rested on Nye to disprove the allegations of fraud. Wintle thus became the first non-lawyer to achieve a unanimous verdict in his favour in the House of Lords. He was also awarded costs.

As well as establishing important principles of the law concerning challenges to wills, the case compelled the Law Society (due to the public outcry) to ban solicitors from drafting wills in their own favour. The House of Lords’ decision is consistent with long-standing principles and authority that a person in a fiduciary position, such as a solicitor, should not be permitted to benefit from abusing that relationship, particularly in the case of an elderly client unversed in business affairs, as in the testator’s case.

After the case, Nye was struck off the roll of solicitors. Wintle, on the other hand, received a jeroboam of champagne from the Temple (Lincoln’s Inn) in congratulations for his spirited advocacy. At the end of ten years, Wintle said, “Perhaps they’re not such a bad lot after all. At least they’re English barristers.”

In June 2018, Fairseat resident Pam Sheldon recorded her memories of Alfred Wintle:

“We came to live in Fairseat in October 1954, and my mother, Gladys Watney, came to help us with the move. She was invaluable and stayed on with my sister Sally, who was away at boarding school. My mother was a keen bridge player and soon got to know AD and Dora Wintle from Coldharbour. They came to play in Court House from time to time, but I did not see them very often, as I didn’t play myself. The first time I saw AD was when I was driving up the A227 one foggy evening, and there in the middle of the road was a lone figure. He made no effort to move over, and I eventually pulled around him and arrived home to find out who he was.

On later acquaintance, I discovered AD had a disregard for the paperwork, such as bills, and once bypassed the demand for his water bill by joining two lengths of pipe around the meter. This, of course, is only an unsubstantiated report!

He died very suddenly, leaving Dora in a lonely house on her own. Her nephew, James Robertson Justice, gave her a King Charles spaniel for company. Unfortunately, he was a neurotic little dog, and Dora had to go into the hospital with a broken hip. The dog (Charlie) came to us and wandered frequently up the A20. We found him a couple in Keston who took a great fancy to him, with a walled garden. But alas, they could not cope with him, and we finally had to get him put down by the vet. In the meantime, Dora had died [in 1974], and we didn’t have a chance to learn more until his book became available.”

Wintle died in May 1966, aged 68, at Coldharbour, his home in Stansted. He died of a clot as he had predicted and was cremated at Maidstone Crematorium. His old friend Cedric Mays had spoken with Wintle several days before his death, discussing the funeral arrangements. In accordance with Wintle’s wishes went to Canterbury Cathedral and, to the consternation of sundry kneeling worshippers, sang Ständchen, Schubert’s Serenade, the Last Post and Reveille.

Wintle began writing in 1924 after he broke his leg while riding a horse. Wintle initially wrote fiction under the pseudonym “Michael Cobb”. His novel The Emancipation of Ambrose (1928) was filmed in 1936 as Wolf’s Clothing. Other works published under the name A.D. Wintle include the fictional biography Aesop (1943), the novel Ilium: A Story of Troy (1944), and The Club (1961). Wintle said in his autobiography: “So I have not been too unhappy as a civilian. I have managed fairly well by writing fiction (and living it, too) to augment the 100% disability pension the Army was good enough to grant me.’

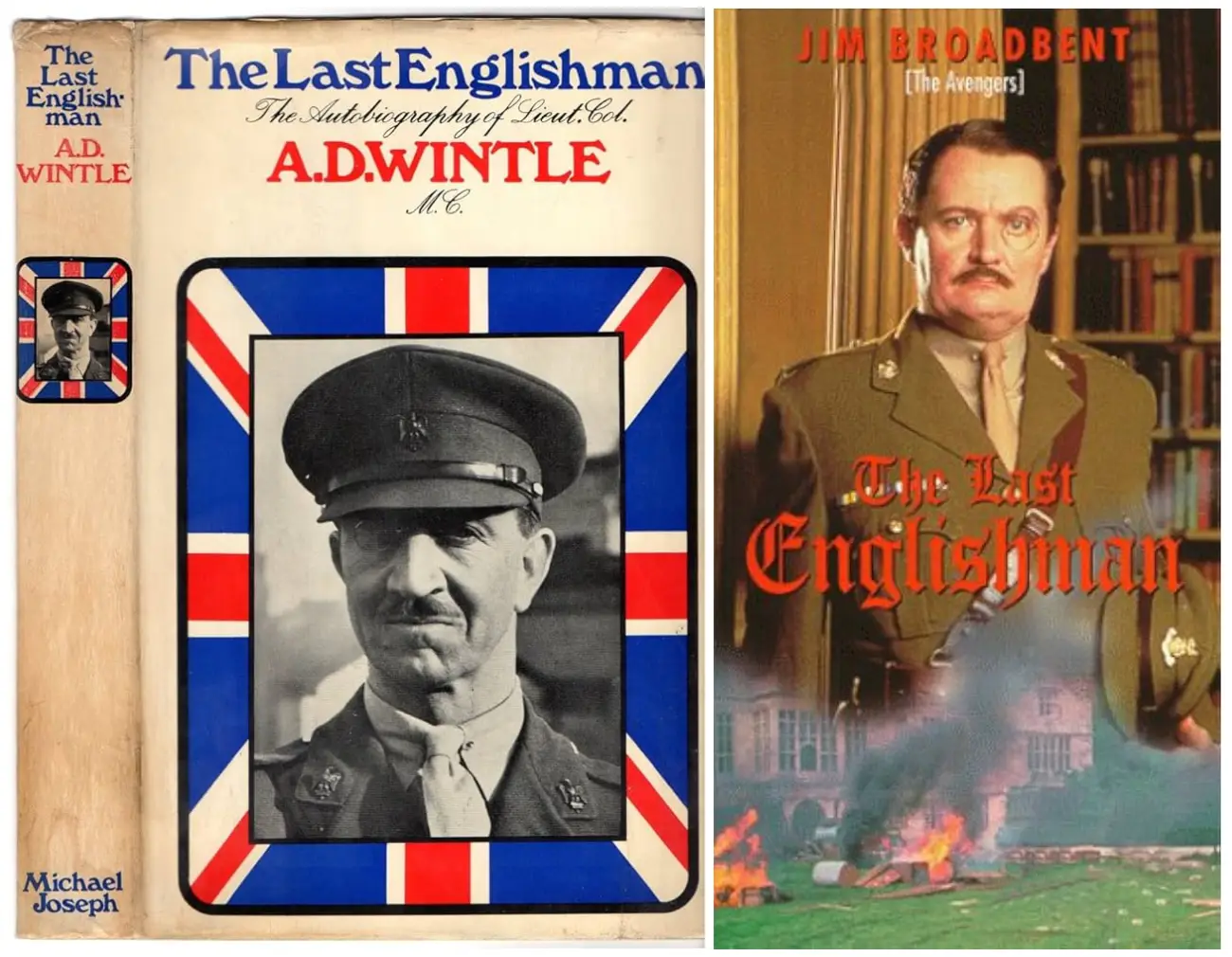

His autobiography, ‘The Last Englishman’, was published in 1968, two years after his death and was compiled from Alfred’s own words by Alastair Revie, a friend, journalist and author.

The following are notable quotes from Alfred Wintle:

- “Assuming one has the honour to be English, the other great gift God can bestow is a sense of humour.”

- “It may have escaped your attention, but there is no fighting to be done in England.” (on being told he was being removed from active duty against his will following an injury)

- “This umbrella was stolen from Col. A.D. Wintle” (note left in his permanently furled umbrella). “No true gentleman would ever unfurl one.”

- “Time spent dismounted can never be regained.”

“No true gentleman would ever leave home without one.” (his monocle) - “A good rule of life is never to be rude to anyone under the rank of full Colonel.”

- “It is impossible to be unhappy on the back of a horse. My feelings on the subject are such that, if I ever had to tackle something really difficult, like threading a needle or delivering a sermon, I should instantly leap on the nearest horse.”

“I did not fall off my horse as a dentist might. A horse fell on top of me and broke my leg.” - “Sometime in 1925, I was sent from Aldershot on a Cookery Course for four days. Cookery! Me!”

- “God has always shown an inclination to favour the English. Let us not risk throwing this splendid advantage away.”

- “The last person who went into the House of Commons with any good intentions was Guy Fawkes. It’s time they had another, like me, with explosive ideas.” (Wintle’s election slogan in 1945).

- “I get down on my knees every night and thank God for making me an Englishman. It is the greatest honour He could bestow. After all, he might have made me a chimpanzee, or a flea, a Frenchman or a German!”

- “What I like about Isherwood’s paintings is that there is no doubt about which way they hang.” (on art)

- “Attend a German school, sir? I would rather cut my hands off and blind myself in one eye. Only an English school is good enough for me.” (young Wintle, on being told by his father that he was to attend a German school)

- “Heaven is to be found on the back of a horse or in the arms of one’s beloved. Note that the conjunction is ‘or’, not ‘and’.”

“There are two classes of insular Englishmen – those who think no foreigner is as good as an Englishman, through sheer ignorance and those who, like me, know it through experience.” - “What is all this nonsense about dying, Mays? You know it is an offence for a Royal Dragoon to die in bed. You will stop dying at once. And when you get up, get your bloody haircut.” (said to Trooper Cedric Mays, 1st Royal Dragoons, who recovered and lived to the age of 95)

- “For a cavalry officer, to be literate, let alone write, is a disgrace.”

- “Sir, I have just written you a long letter. On reading it over, I have thrown it into the waste paper basket. Hoping this will meet with your approval, I am, Sir, Your obedient Servant, AD Wintle.” (Letter to The Times)

Autobiography & Film

A full-length autobiography, ‘The Last Englishman’, was compiled after his death by his friend Alastair Revie from more than a million words left by Wintle, and was published in 1968 by Michael Joseph.

Wintle was a career soldier, and the book explores both his military career and his life beyond the military. His MC was awarded during WW1, though, according to him, he has no recollection of why he was awarded it, and his diary shows he wasn’t even in the trenches at the time. The latter part of the book deals with a legal battle he fought on a matter of principle, which bankrupted him but did lead to a change in the law preventing solicitors from being beneficiaries to wills they have arranged.

In 1995, the BBC released a TV film, ‘The Last Englishman’ as part of its Heroes and Villains series. The film was dramatised by Anthony Horowitz and directed by John Henderson. Jim Broadbent played the role of Wintle.

The title of this hour-long film aptly describes how Colonel Wintle saw himself and lived his eccentric, highly individual life. He had no patience for bureaucracy and red tape and did not even respect orders from his senior officers. He refused to stay in hospital or to be sent home when injured. “Has it escaped your notice? There is no fighting to be done in England.” He is famed for single-handedly capturing a French Village during World War I, only to later wind up in the Tower of London after attempting to shoot his commanding officer.

This true story begins with Wintle’s funeral in the early 60s and is told via flashbacks, narrated by an elderly gentleman holding a solitary wake in a country pub. This old gentleman was Wintle’s batman, who made a seemingly miraculous recovery from mortal wounds sustained on The Somme, his recovery being solely due to Wintle marching to his deathbed and specifically ordering him not to die!

Author: Dick Hogbin

Editor: Tony Piper

Contributors: Pam Sheldon

Acknowledgements: ‘The Last Englishman’, Alastair Revie, 1968, Michael Joseph. Wikipedia. ‘It Takes all Kinds’, Robert Littell, published by Reynal & Co, New York, 1961. ‘A Lance for Liberty’, J.D. Casswell, KC, 1961. Biography of Alfred Wintle – Spring 1989, Victorian Bar News. Thesis on Alfred Wintle by Tony Randall, September 2012.

Last Updated: 01 December 2025