Luminaries: Daphne Oram

Daphne Oram was a British composer and electronic musician. She was one of the first British composers to produce electronic sound and helped establish the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1958.

Daphne was born in 1925 in Wiltshire to James and Ida Oram. She was educated at Sherborne School for Girls, where she was taught piano, organ, and musical composition from an early age. Her father was the President of the Wiltshire Archaeological Society, and her childhood home was within 10 miles of the stone circles of Avebury and 20 miles from Stonehenge.

When she was 17, Oram’s father invited famous medium Leslie Flint to their house in Wiltshire. Flint was quite the celebrity in 1942 and asserted that a voice from beyond foretold that Oram would be a great musician. This may have influenced her father’s decision to allow Daphne to drop out of nursing training in favour of a career in music. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this would also spark Oram’s lifelong interest in mysticism; she even developed her own, often eccentric theories about the connections between soundwaves and the soul.

In 1943, at the age of 18, she was offered a place at the Royal College of Music but instead took up a position as a ‘sound balancer’ at the BBC. During the war, one of her many duties was working on live Proms broadcasts from the Royal Albert Hall. After she had completed the microphone placements and sound balancing, she would tuck herself away high up under the concert hall’s famous glazed dome and hover over a turntable. In the event of a bomb forcing the orchestra to abandon their performance, Oram’s role was to drop the needle on a disc of the piece being played so the broadcast would continue seamlessly.

Oram was largely tasked with providing sound effects for radio dramas. While some of these were innovative, such as soundtracking Samuel Beckett’s ‘All That Falls’, the potential for a whole new musical language remained untapped. She became aware of developments in “synthetic” sound and would work alone at night after broadcasting had ended, pushing around tape recorders to create her own multi-track studio for experimenting with symphonic works.

It was these experiences that partly informed her 1949 composition ‘Still Point’, an exceptional piece for two orchestras and electronics. The original score was also discovered in her archives, with Oram’s neat pencil marks filling page after page of the manuscript. The score was later misplaced for a lengthy period.

Composer, researcher, author and archivist Hugh Davies is another overlooked lynchpin of British electronic music. He spent a couple of years as Karlheinz Stockhausen’s personal assistant in Cologne in the 1960s and later published the ‘International Electronic Music Catalogue’, which sought to list every electronic piece ever recorded. It was Davies who kept the torch burning for Oram’s legacy, and the score for ‘Still Point’ was eventually found among his personal effects after his own death in 2005.

If ever there was a composition ahead of its time, it’s ‘Still Point’. But Oram, who wanted the piece to be entered into the recently launched Prix Italia competition, wasn’t able to muster any enthusiasm for it within the BBC, and it was shelved. It would be nearly seven decades before the piece was finally performed, realised by the composers James Bulley and Shiva Feshareki at the Royal Albert Hall Proms in 2018.

In the 1950s, she was promoted to music studio manager at the BBC and began campaigning for the corporation to provide electronic music facilities for composing sounds and music, and to use electronic music in its programming. In 1957, she was commissioned to compose music for the play Amphitryon 38. Using a sine-wave oscillator, an early tape recorder, and self-designed filters, she produced the score from electronic sources alone – the first of its kind at the BBC. Along with fellow electronic musician and BBC colleague Desmond Briscoe, she began to receive commissions for many other works, including a significant production of Samuel Beckett’s All That Fall.

For years, she lobbied the BBC to take electronic music more seriously, until in April 1958 the corporation set up the Radiophonic Workshop in Room 13 at the Maida Vale complex and appointed her as its first director. The shopping list of advanced studio equipment she had put together, including her plans to create a multitrack recording facility, was unfortunately not supported by BBC management and the facility was started with a budget of £2,000 and a collection of retired equipment from other BBC studios.

A research trip to the ‘Journées Internationales de Musique Expérimentale’ at the Brussels World’s in October 1958 was a reminder of how much more agreeable creative life was for her contemporaries on the continent. It reads like the line-up for Glastonbury for the early electronic music fan – Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Edgard Varèse, Luc Ferrari, Luigi Nono, Bruno Maderna, Luciano Berio, Henk Badings, Herbert Eimert, György Ligeti, Henri Pousseur, John Cage, and Olivier Messiaen.

“Six whole days of experimental music,” she wrote shortly afterwards. “Even without its setting among the brilliant Brussels international exhibition, this prospect would have stirred the expectation of any young, modern musician. There were to be lectures by Stockhausen, Eimert, Berio, Pousseur, and others… compositions by composers from Berlin, Cologne, Italy, Holland and Belgium, and musique concrète by Pierre Schaeffer and his colleagues in France. Surely, at last, this was going to be the opportunity for the new trends in music to stand on their own feet and show that the time had come for full recognition by the musical world.”

After hearing some of the work produced by her contemporaries, Daphne was keen to continue experimenting with electronic music and became frustrated by the limitations at the BBC Workshop, where she and her colleagues were expected to provide only background music and sound effects for the drama producers.

By the end of 1958, Oram believed her vision for a state-backed resource for avant-garde composers had been reduced to a special effects department. Thanks to pressure from the BBC’s in-house musicians, the Radiophonic Workshop’s output couldn’t even be called music. Oram was overworked and underfunded, struggling to create masterpieces of sound design and radical radiophonic composition with inferior equipment. The final straw came when the BBC insisted she could work only three months at a time with the electronic gear before being rotated back to her pre-Radiophonic duties, as if she were in danger of industrial injury from working with electronic waveforms. This suggestion, it seemed, didn’t apply to the male members of the team!

In January 1959, Oram handed in her notice and abandoned her BBC career, leaving the Radiophonic Workshop, the department she had fought so hard to create.

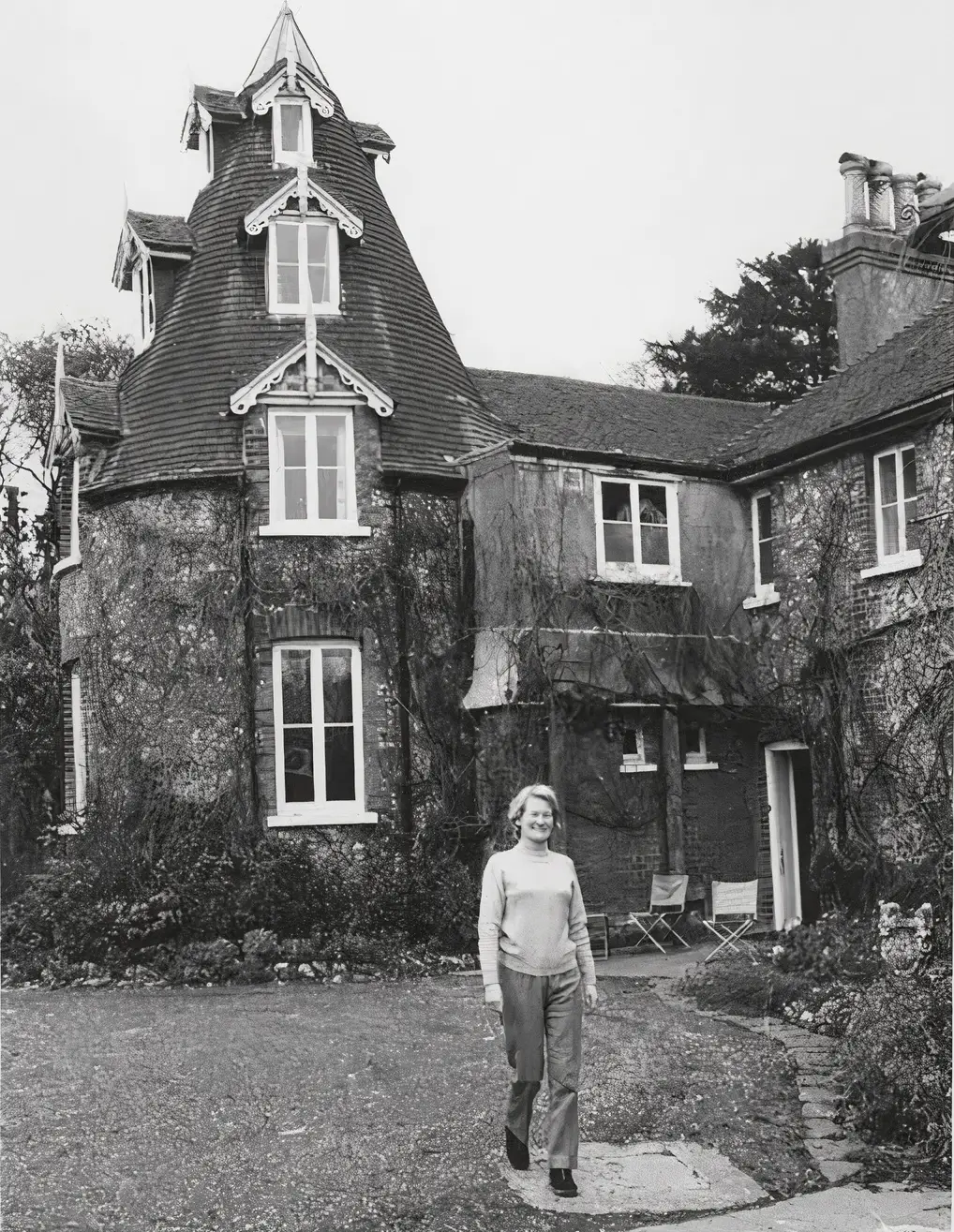

The following BBC Four video is part of the Britain on Film series, the Spirit of the Sixties, featuring 1960s short films that capture the post-war emergence of dynamic youth cultures and celebrate an era when creativity flourished in the music industry. This clip was filmed at Daphne Oram’s music studio in her house, Tower Folly, near Fairseat, Kent.

Oram subsequently set up her own studio in a circular room at the base of a converted oast house, ‘Ye Olde Hop Oaste’, near Fairseat in Kent, renaming this new home ‘Tower Folly’. The property is on the A227 opposite Crabtree Close and was once part of Millers Farm. In addition to setting up studio equipment, Daphne also collected a small menagerie of pets, including cats called Elect, Tronic, Sine and Square.

Oram was the first woman to have an independent studio, and it was there that she produced sounds and music for a wide range of media and performances. She shuttled between Tower Folly and London, taking on commercial work for television and radio advertising, as well as theatre and other commissions.

She composed trail-blazing concert works using tape manipulation; these included Four Aspects (1960), whose twirling melodies, sludgy rhythms and ambient sound-washes were heard at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1968, and the heady, echo-sodden Pulse Persephone, a commission for the 1965 Treasures of the Commonwealth exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. Commercial work (including jingles for Lego and Nestea) helped fund her development of new sound creation techniques.

Legend has it that Oram also received some well-known visitors, including The Who, Mick Jagger and The Beatles. Tantalising as it is to imagine the White Album with Oram in the studio, it was not to be. “She was heard to say that these boys with long hair had come to visit, but it was not really her thing.”

Her output from the studio, mostly commercial, covered a far wider range than that of the Radiophonic Workshop, providing background music not only for radio and television but also for theatre and short commercial films. She was also commissioned to provide sounds for installations and exhibitions. Other work from this studio included electronic sounds for Jack Clayton’s 1961 horror film The Innocents, concert works including Four Aspects and collaborations with opera composer Thea Musgrave.

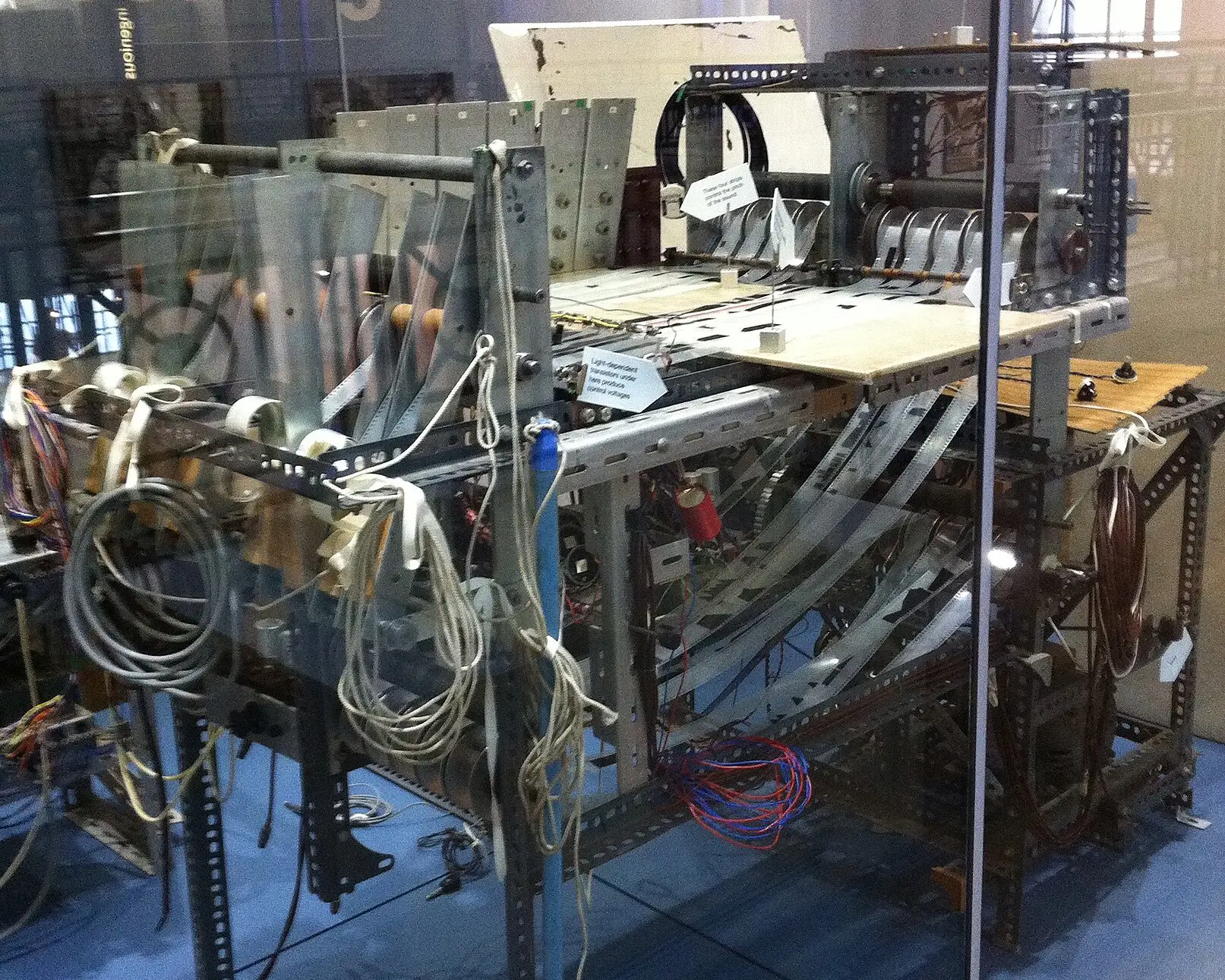

Daphne had encountered a Cathode Ray Oscilloscope, a device which shows a visual image of sound waves, during her time at the BBC. Why not reverse it, she thought? If you paint in waves the ‘shape’ of the sound you want to hear onto 35mm film to determine the pitch, vibrato, timbre, and so on, scanners can then read it and convert it into layered sound. This idea was the beginning of her development of the Oramics Machine, a means of creating sound from hand-drawn input.

In addition to her commercial work, Oram worked tirelessly to develop her concept of ‘Oramics’, a groundbreaking musical composition system that would convert graphical information into sound. It was described by Oram as “A new way of making music with each parameter of the sound required defined by drawing freehand the necessary graphs”. The concept of a ‘graphical music’ system consumed Oram. It typified her view of electronic music not as a soulless, mechanically-controlled thing, but as organic, human, and joyously imperfect as any other music.

In the 1960s, she developed the prototype ‘Oramics Machine’ with funding from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, assisted by her brother John and engineer Graham Wrench. Oram’s composition machine consisted of a large rectangular metal frame that provided a table-like surface traversed by ten synchronised strips of clear, sprocketed 35mm film, which covered a series of photoelectric cells that, in turn, generated an electrical charge to control the frequency, timbre, amplitude, and duration of a sound. This technique was similar to the work of Yevgeny Sholpo’s ‘Variophone’ some years earlier in Leningrad. Although the machine’s output was monophonic, the sounds could be added to multitrack tapes to add texture and create polyphony. According to Oram, “Every nuance, every subtlety of phrasing, every tone gradation or pitch inflection must be possible just by a change in the written form, one that would allow the musician to become much more involved in the sound’s production”

John Deacon, a local resident living in Crabtree Close, which is opposite Tower Folly on the Gravesend Road, recalls the following: “When I worked at the local BT telecommunications tower, we used to get a visit from the Radio Spares representative who would also visit Daphne at her studio, and shortly afterwards, I would get an invitation to tea. Daphne would be interested in any changes to the telecommunication station’s equipment and was keen on preserving the local countryside. When the telephone exchange was built, she insisted that the trees removed be replaced and ensured they were cared for. She had two goats and used to take them to the village shop in Fairseat via the bridle path where we lived. We would see her hanging on for dear life as the Goats pulled her along the track! At Christmas time, we would get a card from Daphne and the goats, whose names were Deci and Bell, named after the unit of sound, the Decibel. Daphne was very independent, living by herself in Tower Folly. During her time there, we had several severe snowstorms when I used to call on her to see if she needed any supplies. The Folly was very cold; I do not think she had a modern heating system. I last saw her when she was in the West Bank care home in Borough Green, but by then she was near the end and I am not sure she knew who I was.”

Daphne had suffered two strokes in the 1990s and was forced to stop working, later moving to a nursing home where she sadly died in 2003, aged 77.

After her death, a large archive of her life’s work was passed to the composer Hugh Davies, and upon his death in 2005, this material passed to Sonic Arts Network. Daphne Oram’s family have now agreed that the archive will reside at the Music Department of Goldsmiths College in London, where it will be open for public access and ongoing research.

It is unclear what happened to the Oramics machine after Oram’s death, and there’s something of a veil of discretion drawn across the circumstances of how it ended up in France, in a barn in Normandy, which was apparently intended to be a synthesiser museum. But that’s where it was found in 2009, literally covered in dust and cobwebs, tracked down by Mick Grierson, co-founder of the Daphne Oram Trust. It was brought back to the UK and put into the care of the Science Museum.

The Science Museum held an exhibition ‘Oramics to Electronica’ in 2011, which explored the history of electronic music through the work of three British studios: Electronic Music Studios (EMS), the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Daphne Oram’s studio in Tower Folly, Kent.

The unique instrument she developed over the years, the Oramics Machine, was at the heart of the exhibition. The original Oramics Machine, remarkably intact after languishing for many years in a barn in France. All four elements of the Oramics apparatus were on display: the control console, loudspeaker cabinets, waveform scanner and amplifier. The control console will be familiar to anyone who has seen the famous photos of Oram painting waveforms on celluloid and glass as she leans over her machine.

This exhibition was an unparalleled opportunity to see Oram’s groundbreaking and historic machine. Dr Tim Boon, head of Science Museum research, remarked how little of Oramics machine had been lost or altered since it was last used by Oram. Only the celluloid film strips that moved across the control console had to be replaced before it went on display. The originals had become discoloured, warped and too brittle to conserve in situ.

The following BBC video outlines the development of electronic music and features Daphne Oram’s ‘Oramics Machine’, on display at the Science Museum during the ‘Oramics to Electronica’ exhibition in 2011.

Daphne’s contribution to electronic music was celebrated when the Daphne Oram Creative Arts Building opened at Canterbury Christ Church University in the summer of 2019. Oram was a tutor at Canterbury Christ Church College between 1982 and 1989, where she taught weekly electronic music classes. This building celebrates her name and legacy as it opens to a new generation of staff and students.

The new space, designed for twenty-first-century creative arts, also celebrates the historic foundations of the Christchurch campus, exposing sections of the original St Augustine’s Abbey wall beneath a glass floor. Spaces flooded with natural light are equipped with the latest digital facilities to support creative work, enabling students to generate and share ideas.

Further information on Daphne Oram can be found on the Daphne Oram Trust’s website. The Trust is registered with the Charity Commission under number 1134910.

https://www.daphneoram.org/

Author: Tony Piper

Contributors: John Deacon

Acknowledgements: The BBC, Canterbury Christ Church University, The Daphne Oram Trust, The Science Musuem

Last Updated: 04 November 2025